Table of Contents

DEDICATION

For those who havent found their way out yet; and for those of us who have, and will always remember.

Prologue

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the one who find our way

back to this scene...

FROM DIVING INTO THE WRECK,

BY ADRIENNE RICH

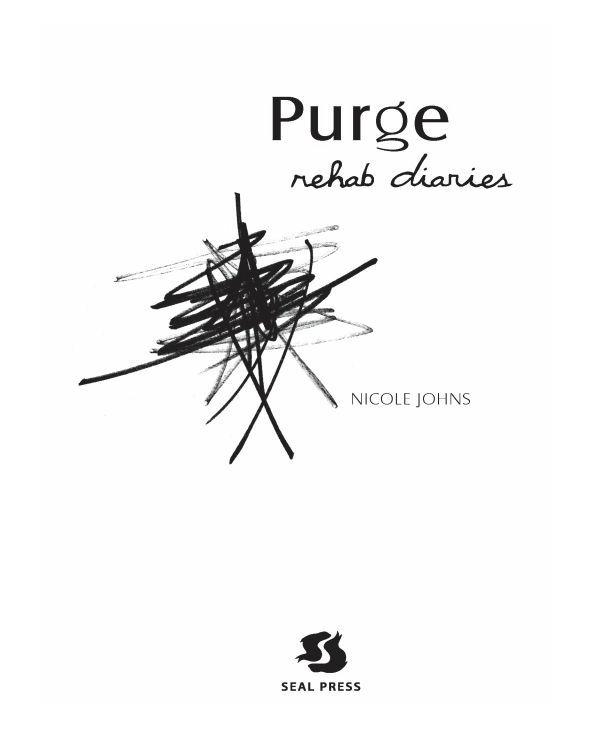

I have used Adrienne Richs poem Diving into the Wreck as a metaphor to describe the process of writing this book, as well as my recovery from an eating disorder. I have had to dive into the wreck of my journals, my medical and psychiatric records, the minds of those who accompanied me during my three months of treatment, and my own mind in order to find my way back to the scene and accurately record my experience. I chose to write about the three months I spent in residential treatment for Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS) because there is a dearth of well-written, timely, and accurate literature about eating disorder treatment.

Numerous psychological studies have been published regarding the success rates of various methods of treating eating disorders. While such studies are integral to healthcare professionals understanding of how to better treat eating-disordered individuals, they do not tell the story of the individual who struggles with an eating disorder, or her treatment experience. Although a recent explosion of self-help books addresses the topic of eating disorders, these books often offer dubious advice and are poorly written.

Another genre of eating disorder books exists: a cross between the traditional self-help book and the memoir. In these books, the narrator is saved by a treatment provider or God, or a combination of both. These books give the reader the impression that an eating disorder is just a diet gone wrong, and that it can be cured if the individual finds the right support group, the right religion, or the right therapist.

Unfortunately, it is not that simple. Eating disorders are complex pathologiesthey do not stem from a single source, they have no simple resolution, and they are seldom cured. Treatment can help an individual lessen her symptoms (restricting, purging, and so on) and obtain a better quality of life. However, treatment does not cure an eating disorder. What the general public does not realize is that the eating-disordered individual struggles and needs continued support after leaving treatment, and that, to some extent, she will struggle with eating disorder urges after treatment, even if she doesnt act on them. The happily ever after ending of many of the eating disorder books on the market today is a myth.

One of my main goals in writing this book is to reveal that despite having spent three months in treatment, I am not cured, and neither are the majority of patients. I wanted to write an honest, detailed narrative about my experience in treatment and the effect it had on my life. I wanted to show the reader that there is no happily ever after, but that there is hope. Most of the current eating disorder literature glosses over the ugly parts of living with and attempting to recover from an eating disorder. I chose specifically to describe what it is like to purge, what it is like to abuse diet pills and starve myself. The readers deserve to know the truth, rather than have it sugar-coated. For this reason, I also included a number of primary documents from my stint in treatment. Along with aiding the structure of my book, these documents detail my treatment experience and offer the reader a clearer idea of the treatment process.

Most of the literature about eating disorders written by treatment providers and individuals who have battled an eating disorder creates the unrealistic expectation that the readers eating disorder will be cured after one round of treatment, after a few therapy sessions, or after the eating-disordered individual reaches a healthy weight or stops purging. The reality of eating disorder treatment is that the relapse rate is astronomical. According to the Cleveland Clinic, up to 50 percent of bulimics relapse six months after treatment, and the relapse rate for anorexia is even higher.

We as readers are living in the age of the memoir. Memoirs, especially those dealing with subjects previously deemed taboo by society, are selling well. Eating disorders have not gone undocumented in this era.

The preeminent eating disorder memoir is Wasted, by Marya Hornbacher. As a senior in college, I checked out Wasted from the library and read the book in one day, as I was riveted by Hornbachers description of her battle(s) with anorexia and bulimia. At the time, I was in the throes of purging anorexiamy goal was to eat less than seven hundred calories a day; I purged if I exceeded my self-imposed limit, in an effort to lose weight and gain control over something in my life: my body.

It is worth noting that Wasted has a cult following of eating-disordered individuals. While I was in treatment, several women attempted to smuggle Wasted into the treatment facility, but the staff confiscated their dog-eared copies of the book. These women considered Wasted their eating disorder bible; they gleaned tips from it and used it to trigger their own eating disorder behaviors.

The cover of Wasted was what first caught my attention. The paperback edition of the book showcases a thin Hornbacher on its front cover. To non-eating-disordered women, this visual of the author and what she has done to her body may serve as a warning. But all I saw was that she was thin.

As a reader, I searched for firsthand accounts of what life in a treatment center is like, and was left unsatisfied. As I progressed through treatment, I learned that I was not the only one without a clear idea of what eating disorder treatment entails. Well-meaning friends thought it was like summer camp, while others thought Id be spending time on lockdown with psychotic individuals. The reality of the treatment experience (or at least my treatment experience) was quite different from what most people imagine. My hope is that this book dispels the myths about eating disorder treatment that are circulating.

Another myth I hope to dispel is that anyone who is not emaciated cannot have an eating disorder. At 137 pounds, in the midst of consuming diet-pill cocktails, starving, and purging, I was hospitalized for fainting, a concussion, electrolyte imbalances, and three different kinds of heart-rhythm irregularities. My eating disorder behavior had wreaked havoc on my body. Not until after treatment did I learn the sum total of the damage I had done, but for a long time I refused to believe I had a problem because I was not underweight.

In treatment, I met overweight and normal-weight bulimics with an array of medical problemsincluding heart irregularities, eroded esophageal tracts, bowel problems, osteopenia, and osteoporosisat the age of twenty. A person does not have to be underweight to suffer the medical consequences (not to mention the emotional pain) of an eating disorder. An eating-disordered individual should not have to weigh fifty-two pounds to be taken seriously.

In conclusion, I wrote this book to inform the public, counteract the myths surrounding eating disorders and treatment, and provide eating-disordered individuals with hope.

While most eating disorder patients are female, it should be noted that increasing numbers of males are seeking treatment for eating disorders.