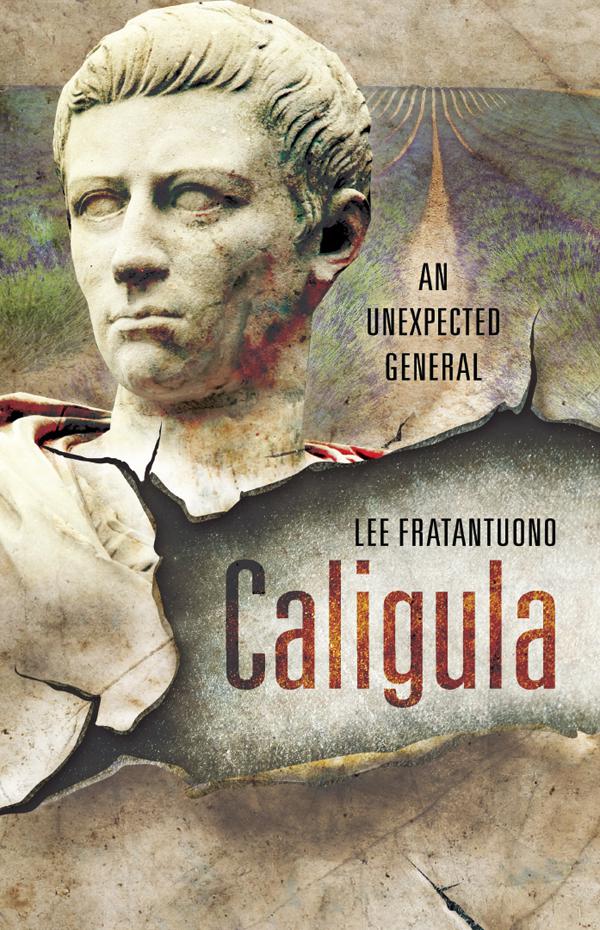

Caligula

Caligula

An Unexpected General

Lee Fratantuono

(with photographic illustration by Katie McGarr)

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Lee Fratantuono 2018

ISBN 978 1 52671 120 5

eISBN 978 152671 122 9

Mobi ISBN 978 152671 121 2

The right of Lee Fratantuono to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology,

Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military

Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing,

Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press,

Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and

White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

For Professor Thomas Runge Martin

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

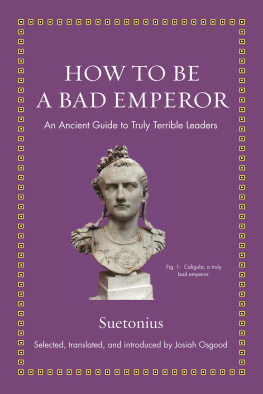

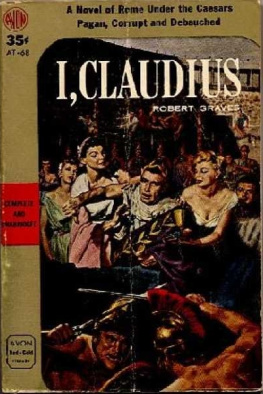

Another book on the emperor Caligula invites (indeed demands) explanation and justification. For many years, the standard English biography/history of Caligula and his reign was the work of J.P.V.D. Balsdon, The Emperor Gaius (Caligula) . This 1934 Oxford monograph revealed something of its intention even from the imperial nomenclature of its title: it would be a serious study of an emperor who was far more complex, and far less crazed, than the ancient treatments of Romes notorious emperor from the pens of Suetonius and others would suggest. This was to be a book about the emperor Gaius, not the madman Caligula whose monstrous deeds fill the pages of Suetonius life and have grimly mesmerized so many across time and space. Coincidentally, Balsdons work appeared in the same year as the historical novel of Robert Graves, I, Claudius a work that is better known today thanks to British television than to the original (and captivating) novel and its sequel, Claudius the God . There is no question that the general perception of Caligula owes more to Graves than to Balsdon.

Balsdon was supplanted in some ways by Anthony Barretts Caligula: The Corruption of Power , which appeared from Yale University Press in 1989. Barretts magisterial treatment of Caligula would reappear in a significantly revised second edition of 2015 from Routledge, with the new title, Caligula: The Abuse of Power (Barrett explains in the preface to the second edition that he is more inclined now to believe that Caligula was essentially unfit for office from the start, and that he abused power rather than suffered corruption because of it). The second edition of Barrett was in part motivated by the many books on Caligula that appeared after the first, prominent among them being three English commentaries on Suetonius life of the emperor (by David Wardle, Hugh Lindsay and Donna Hurley). All three are invaluable aids for the study of Caligula and his reign.

The three major Suetonian commentaries on the Caligula offer detailed notes on the Latin text of Suetonius an author who has been served splendidly in recent years by the appearance of a new Oxford text of Robert Kaster, complete with companion volume on textual problems in the Lives of the Caesars .

Barretts work is certainly in the general school of Balsdon, though with a more balanced approach to the princeps . Readers who come to Barrett from Balsdon will not find so many ready excuses of Caligulas behaviour, or so much effort expended in defending the emperor against a hostile historiographical tradition. But the general approach is similar, and the conclusions not vastly dissimilar though Caligula will likely never find another apologist as devoted as Balsdon.

Some voices have been raised in defence of the ancient tradition of Caligula as insane monster. Here the work of Arther Ferrill holds sway. His 1991 Thames and Hudson study, Caligula: Emperor of Rome , has a neutral title for a book that dismisses the arguments of those who would try to sanitize the Caligulan reign. For Ferrill, while this or that detail of the historical record may be suspect, on the whole the ancient narrative is sound, and Caligula was insane. Ferrills book has been criticized by some for being a less than critical assessment of the Caligulan principate, a volume that ultimately takes almost everything said by a Seneca or a Tacitus at face value or as gospel truth. These criticisms are not entirely fair, though in the end Ferrill stands on one extreme and Balsdon on the other, with Barrett somewhere betwixt the two, though far closer to his Oxonian predecessor Balsdon than to Ferrill. Ferrill is in some ways a valuable counterbalance to his more sympathetic predecessors. At the very least, he serves as a reminder that we are possessed of too little evidence about the Caligulan principate to be sure of even the most general lines of interpretation of his reign. Tacitus has been viewed with suspicion by some for not being so removed from the anger and partisanship that he refers to in his own work ( sine ira et studio , etc.) but we sorely miss the Tacitean treatment of the Caligula years. Indeed, we may wonder if it is noteworthy that his principate is missing from the manuscript tradition of the Annales . The simple fact is that as for many luminaries of Roman history, we are missing considerable information about Caligulas life. All Caligula monographs are probably too long the temptation to speculate is so great. That said, his reign has undeniable intrinsic interest, and apart even from the perhaps inevitable indulgence in the lurid that his life invites, his reign is of unquestioned significance in the development and progress of the Julio-Claudian principate.

Barretts book has enjoyed translations into foreign languages, and Aloys Winterlings 2003 German monograph on Caligula ( Caligula: Eine Biographie ) has been translated into English (2011). Winterling is very much in the school of Balsdon; like others of the same school, he finds the story of Caligulas sororial incest to be suspicious, and he engages in the same rationalization and careful defence that Balsdon practices. Pierre Renuccis 2011 French language monograph Caligula , for ditions Tempus Perrin, sees a link between the defects in character attributed to Caligula, and the very milieu and structure of Julio-Claudian Rome. Renuccis work is very much in the mold of Barrett, seeking not so much to rehabilitate Caligula as to offer a more nuanced appraisal of his life and deeds. Renuccis study of Caligula follows admirably on his work on Auguste, le rvolutionnaire (2003) and Tibre, lempereur malgr lui (2005), all to be highly recommended to francophone students of the Julio-Claudians (Renucci also has a 2012 Claudius in his series). In Arther Ferrills Bryn Mawr Classical Review of Barrett, he notes that exceedingly little new evidence was unearthed in the half century between Balsdon and Barrett: fair enough. The same is true for the nearly three decades since the first edition of Barrett.