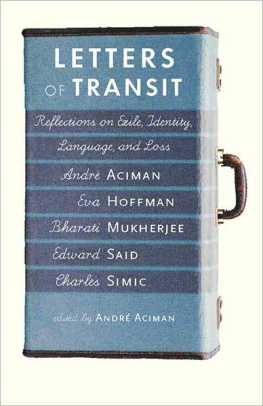

Lost in Trans lation

A Life in a New Language

by Eva Hoffman

To my family, which has given me my first world,

and to my friends, who have taught me how to appreciate

the New World after all.

Part I

PARADISE

It is April 1959, Im standing at the railing of the Batory s upper deck, and I feel that my life is ending. Im looking out at the crowd that has gathered on the shore to see the ships departure from Gdynia a crowd that, all of a sudden, is irrevocably on the other side and I want to break out, run back, run toward the familiar excitement, the waving hands, the exclamations. We cant be leaving all this behind but we are. I am thirteen years old, and we are emigrating. Its a notion of such crushing, definitive finality that to me it might as well mean the end of the world.

My sister, four years younger than I, is clutching my hand wordlessly; she hardly understands where we are, or what is happening to us. My parents are highly agitated; they had just been put through a body search by the customs police, probably as the farewell gesture of anti-Jewish harassment. Still, the officials werent clever enough, or suspicious enough, to check my sister and me lucky for us, since we are both carrying some silverware we were not allowed to take out of Poland in large pockets sewn onto our skirts especially for this purpose, and hidden under capacious sweaters.

When the brass band on the shore strikes up the jaunty mazurka rhythms of the Polish anthem, I am pierced by a youthful sorrow so powerful that I suddenly stop crying and try to hold still against the pain. I desperately want time to stop, to hold the ship still with the force of my will. I am suffering my first, severe attack of nostalgia, or t s knota a word that adds to nostalgia the tonalities of sadness and longing. It is a feeling whose shades and degrees Im destined to know intimately, but at this hovering moment, it comes upon me like a visitation from a whole new geography of emotions, an annunciation of how much an absence can hurt. Or a premonition of absence, because at this divide, Im filled to the brim with what Im about to lose images of Cracow, which I loved as one loves a person, of the sun-baked villages where we had taken summer vacations, of the hours I spent poring over passages of music with my piano teacher, of conversations and escapades with friends. Looking ahead, I come across an enormous, cold blankness a darkening, an erasure, of the imagination, as if a camera eye has snapped shut, or as if a heavy curtain has been pulled over the future. Of the place where were going Canada I know nothing. There are vague outlines of half a continent, a sense of vast spaces and little habitation. When my parents were hiding in a branch-covered forest bunker during the war, my father had a book with him called Canada Fragrant wi th R esin which, in his horrible confinement, spoke to him of majestic wilderness, of animals roaming without being pursued, of freedom. That is partly why we are going there, rather than to Israel, where most of our Jewish friends have gone. But to me, the word Canada has ominous echoes of the Sahara. No, my mind rejects the idea of being taken there, I dont want to be pried out of my childhood, my pleasures, my safety, my hopes for becoming a pianist. The Batory pulls away, the foghorn emits its lowing, shofar sound, but my being is engaged in a stubborn refusal to move. My parents put their hands on my shoulders consolingly; for a moment, they allow themselves to acknowledge that theres pain in this departure, much as they wanted it.

Many years later, at a stylish party in New York, I met a woman who told me that she had had an enchanted childhood. Her father was a highly positioned diplomat in an Asian country, and she had lived surrounded by sumptuous elegance, the courtesy of servants, and the delicate advances of older men. No wonder, she said, that when this part of her life came to an end, at age thirteen, she felt she had been exiled from paradise, and had been searching for it ever since.

No wonder. But the wonder is what you can make a paradise out of. I told her that I grew up in a lumpen apartment in Cracow, squeezed into three rudimentary rooms with four other people, surrounded by squabbles, dark political rumblings, memories of wartime suffering, and daily struggle for existence. And yet, when it came time to leave, I, too, felt I was being pushed out of the happy, safe enclosures of Eden.

I am lying in bed, watching the slowly moving shadows on the ceiling made by the gently blowing curtains, and the lights of an occasional car moving by. Im trying hard not to fall asleep. Being awake is so sweet that I want to delay the loss of consciousness. Im snuggled under an enormous goose-feather quilt covered in hand-embroidered silk. Across the room from me is my sisters crib. From the next room, the first room, I hear my parents breathing. The maid one of a succession of country girls who come to work for us is sleeping in the kitchen. It is Cracow, 1949, Im four years old, and I dont know that this happiness is taking place in a country recently destroyed by war, a place where my father has to hustle to get us a bit more than our meager ration of meat and sugar. I only know that Im in my room, which to me is an everywhere, and that the patterns on the ceiling are enough to fill me with a feeling of sufficiency because... well, just because Im conscious, because the world exists and it flows so gently into my head. Occasionally, a few blocks away, I hear the hum of the tramway, and Im filled by a sense of utter contentment. I love riding the tramway, with its bracing but not overly fast swaying, and I love knowing, from my bed, the street over which it is moving; I repeat to myself that Im in Cracow, Cracow, which to me is both home and the universe. Tomorrow Ill go for a walk with my mother, and Ill know how to get from Kazimierza Wielkiego, the street where we live, to Urzdnicza Street, where Ill visit my friend Krysia and already the anticipation of the walk, of retracing familiar steps on a route that may yet hold so many surprises, fills me with pleasure.

Slowly, the sights and sounds recede, the words with which I name them in my head become scrambled, and I observe, as long as possible, the delicious process of falling asleep. That awareness of subsiding into a different state is also happiness.

Each night, I dream of a tiny old woman a wizened Baba Yaga, half grandmother, half witch, wearing a black kerchief and sitting shriveled and hunched on a tiny bench at the bottom of our courtyard, way, way down. She is immeasurably old and immeasurably small, and from the bottom of the courtyard, which has become immeasurably deep, she looks up at me through narrow slits of wise, malicious eyes. Perhaps, though, I am her. Perhaps I have been on the earth a long, long time and thats why I understand the look in her eyes. Perhaps this childish disguise is just a dream. Perhaps I am being dreamt by a Baba Yaga who has been here since the beginning of time and I am seeing from inside her ancient frame and I know that everything is changeless and knowable.

Its the middle of a sun-filled day, but suddenly, while shes kneading some dough, or perhaps sewing up a hole in my sweaters elbow, my mother begins to weep softly. This is the day when she died, she says, looking at me with pity, as if I too were included in her sorrow. I cant stop thinking about her.

I know who she is; I feel as if Ive always known it. Shes my mothers younger sister, who was killed during the war. All the other members of my mothers family died as well her mother, father, cousins, aunts. But its her sister whose memory arouses my mothers most alive pain. She was so young, eighteen or nineteen She hadnt even lived yet, my mother says and she died in such a horrible way. The man who saw her go into the gas chamber said that she was among those who had to dig their own graves, and that her hair turned gray the day before her death. That strikes me as a fairy tale more cruel, more magical than anything in the Brothers Grimm. Except that this is real. But is it? It doesnt have the same palpable reality as the Cracow tramway. Maybe it didnt happen after all, maybe its only a story, and a story can be told differently, it can be changed. That man was the only witness to what happened. Perhaps he mistook someone else for my mothers sister. In my head, without telling anyone, I form the resolve that when I grow up, Ill search the world far and wide for this lost aunt. Maybe she lived and emigrated to one of those strange places Ive heard about, like New York, or Venezuela. Maybe Ill find her and bring her to my mother, whose suffering will then be assuaged.

Next page