Foreword

Permanent Transients

Andre Aciman

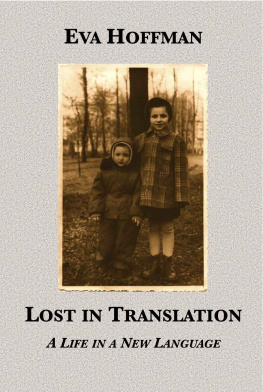

What does it mean to be an exile? How does exile alter someone? How does it reinvent one? What is exile? When does it go away? Does it ever go away? What is the difference between, say, a refugee and an expatriate, or between an immigrant and an emigrant, or between the uprooted and the unrooted, the displaced, the depayses, the evicted, the emigres ?people who didnt just lift themselves up with their roots but who may have no roots left at all? These are the issues each of the five authors gathered here has tried to address in these essays originally delivered in The New York Public Librarys lecture series Letters of Transit. Everyones exile is different, and every writer has his or her own way of groping in the dark. Some have triumphed over exile. Others even found displacement exciting, invigorating. Others were able to don it and doff it, like a costume, while others have never been able to shake it off. But exile, however exiles deal with it, is never far behind, whether were talking of a Yugoslavian in exile (Charles Simic), or a Bengali in exile (Bharati Mukherjee), or a Pole in exile (Eva Hoffman), or a Palestinian in exile (Edward Said), or an Alexandrian in exile (Andre Aciman). Each one of the writers here writes from overt, or, more frequently, covert homesicknesstales of memory, loss, fear, anger, inevitable acculturation, muffled irony in the face of self-pity, and final redemption in this strange and often sorely unnatural thing called naturalization. Having chosen careers in writing, each uses the written word as a way of fashioning a new home elsewhere, of revisiting, transposing, or perpetuating the old one on paper, writing away the past the way one writes off bad debts, doing the one absurd thing all exiles do, which is to look for their homeland abroad, or to try to restore it abroad, or, more radical yet, to dispose of it abroad. However successful the endeavor is by the end of the day, the same perplexities, the same homesickness stirs to life again the next morning.

What makes exile the pernicious thing it is is not really the state of being away, as much as the impossibility of ever not being awaynot just being absent, but never being able to redeem this absence. You look back on your life and find your exile announced everywhere, from events shaped as far back as the Congress of Vienna in 1815 down to the fact that, for some fortuitous reason, your parents decided to make certain you learned English as a child. Bewildered by narratives that pullulate everywhere he looks, an exile has yet to answer a far more fundamental question: in what language will he express his confused awareness of these intimate paradoxes?

Paradoxically enough, the answer in these five cases is Englishthe foreign tongue.

#

Five voices, five tales, five worlds, five lives that might have little in common but for the fact that none of the foreign-born authors gathered in this volume is a native speaker of English. English, for all five, is an acquired language, a foreign idiom, and it remains, perhaps against their will and more than they care to own, alien, strange, distant. After many decades in the United States, or Canada, or England, most still speak English with an accent, as though an accent didnt betray just the bodys inability to adapt or to square away the details of a naturalization that should have been finalized decades ago, but its reluctance to let go of things that are at once private and timeless, the way childhood and ritual and memory are private and timeless. Some of the writers still make out traces of an accent in their own prose, call it a particular cadence in a language that is never quite just English but not anything else either. An accent is the tell-tale scar left by the unfinished struggle to acquire a new language. But it is much more.

It is an authors way of compromising with a world that is not his world and for which he was not and, in a strange sense, will never be prepared, torn as hell always remain between a new, thoroughly functional here-and-now and an old, competing altogether-out-there that continues to exert a vestigial but enduring pull. An accent marks the lag between two cultures, two languages, the space where you let go of one identity, invent another, and end up being more than one person though never quite two.

Yet all five of these authors are so thoroughly at home rooted might be the more appropriate, if ironic, termin English that it is difficult to remember they come from an entirely different hemisphere. English has become the language they speak at home. They write almost exclusively in English, and ultimately count, sing, cook, quarrel, and dream in English. Those of them who have children have tried to pass on the ur-language with varying degrees of success. But the ur-anything pales when it comes to report cards, baseball practice, television, college applications, careers. English is the everyday, nuts-and-bolts language. It may not be the language of the heart, the language of grief and gossip and good-night kisses; but all of these authors write in English when they write from the heart.

Every successful sentence they write reminds them that theyve probably made it to safety. It is, after all, a source of no small satisfaction to be mistaken for a native speaker. Theirs, however, is the satisfaction that men like Demosthenes and Moses might have felt on telling their closest admirers that what turned them to public speaking was not the power of their beliefs but something as trivial as a speech defect. Foreigners frequently master the grammar of a language better than its native speakers, the better, perhaps, to hide their difference, their diffidence, which also explains why they are so tactful, almost ceremonial, when it comes to the language they adopt, bowing before its splendor, its arcane syntax, to say nothing of its slang, which they use sparingly, and somewhat stiffly, with the studied nonchalance of people who arent confident enough to dress down when the need arises.

Eventually, of course, one does stop being an exile. But even a reformed exile will continue to practice the one thing exiles do almost as a matter of instinct: compulsive retrospection. With their memories perpetually on overload, exiles see double, feel double, are double. When exiles see one place theyre also seeingor looking foranother behind it. Everything bears two faces, everything is shifty because everything is mobile, the point being that exile, like love, is not just a condition of pain, its a condition of deceit.

Or put it another way: exiles can be supremely mobile, and they can be totally dislodged from their original orbit, but in this jittery state of transience, they are thoroughly stationaryno less stationary than those displaced Europeans perpetually awaiting letters of transit in the film Casablanca. They are never really in Casablanca, but they are not going anywhere either. They are in permanent transience.

Exiles see two or more places at the same time not just because theyre addicted to a lost past. There is a very real, active component to seeing in this particularly heightened retrospective manner: an exile is continuously prospecting for a future homeforever looking at alien land as land that could conceivably become his. Except that he does not stop shopping for a home once hes acquired one or once hes finally divested himself of exile. He goes on prospecting, partly because he cannot have the home he remembers and partly because his new home bears no relationship to the old. Over and above these minor distinctions, however, his problem starts at home, with home. There isntand, in certain cases, wasntany.

The question our five writers ask is how do you indeed, can you everrebuild a home? What kinds of shifts must take place for a person to acquire, let alone accept, a new identity, a new language? The answers are different, not just because their voices and concerns are different, but because the psychological raw material which each author brings to the puzzle is different as well. Still, here, in this volume, all five authors have shown us how each, in his or her way, has tried to make a home and refashion a life. Lets bear in mind that the next time we read them they wont be as forthcoming. Like friends who happened to open up one day only to withdraw afterwards, theyll be addressing a host of other issues, almost forgetting they showed us their deepest and most private side here.

Next page