better

off

Flipping the Switch on Technology

ERIC BRENDE

To Mary

(and in repose, John Senior)

What follows in these pages is the story of an unusual adventure taken by my wife and me as an adjunct to my graduate studies at M.I.T. Because of the highly personal nature of much of the material and the low tolerance for publicity of the extraordinary people we lived with, their names have been changed, minor details altered, and the location kept secret. Nonetheless, although certain liberties have been taken with chronology and background circumstance, everything described in this book actually took place.

Readers have some options in how they choose to proceed. The story can be read the way stories usually are, that is, as entertainment (I hope riveting), or as food for thought on the broader human condition (I hope stimulating), or even in this case as a real-life model for practical action (I hope instructive).

For those inclined there is still another way to read the book, and that is as a sort of scientific experiment attempting to establish, among other things, the answer to a key question about technologynamely, How much is enough? I say sort of scientific because, although anyone can replicate it, the conditions will probably not be identical.

Contents

E-book Extras:

Prologue

Taking Orders

Section I:

Planting

Section II:

Growing

Section III:

Harvesting

Epilogue

Recipe for a Leisurely, Laborsaving Life

(in order of appearance)

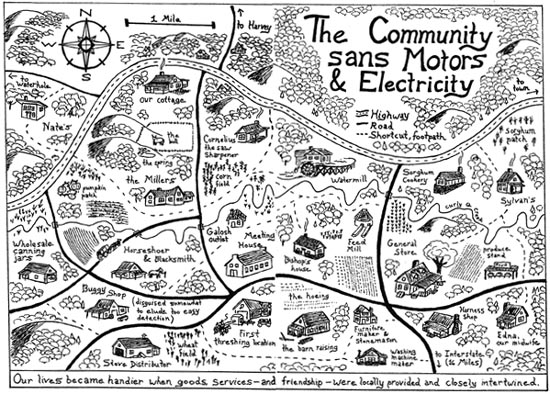

MR. MILLERour landlord and mentor

MRS. MILLERhis wife

AMOS, CALEB, JUDY, ELLIS, IRMA, JED, and HAROLDtheir at-home children

NATE and CAROL JONESfellow escapees from the technological world

GIDEON STOLTZFUSbuilder of the water mill and horse-powered turnstile

ALVIN STOLTZFUScollaborator with Gideon on the water mill

SYLVANMr. Millers son-in-law, collaborator on my sorghum crop

BISHOP HENRYbishop of the community

MINISTER JAMESskilled preacher

ROB, JOHN, HOWIE, ELI, RED, SIM, ELBERTcrew at the barn raising

BILLnovice from the outside world

FREDparticipant in a hoeing

EDWARDBills well-educated boss and mentor, candidate for the ministry

GRACEEdwards wife

HARVEYMr. Millers oldest married son and pig salesman

GERTIEhis wife

CORNELIUSa hermit and saw sharpener

EDNAour midwife

WILBURproponent of green manure, candidate for the ministry

NAOMIthe midwifes apprentice (Mr. Millers sometimes-away daughter)

MR. BERNHARDTadventurous would-be motorist

T he other day someone I know was running an errand in the outer reaches of a major city. She rarely drives, but for some reason had this day dared to hazard the maze of crowded freeways and interchanges. When rush hour came on, she quickly wearied and pined for a break. A sign for a fast-food place came up, and against her better judgment, she pulled over. Seeing no one at the drive-thru, she slid into the ordering station.

She waited three full minutes before anyone responded, even though hers was the only car in line. Then a male voice came over the microphone:

Just one moment please.

She waited another sixty seconds.

Finally the voice resumed: May I take your order?

One small French fries please.

Anything else?

No thank you.

Pull ahead.

At the window a young man who appeared well fed on fries said, Uh, were learning to use a new cash register, so itll be about a ten- to fifteen-minute wait.

Ten to fifteen minutes for one order of French fries?

There was a pause as the young man took in my friends bewilderment.

Uh, I see what you mean. But I dont know how to do it. Why dont you pull ahead to the next window.

At the next window, a slightly older female, who might have been the manager, again fielded the request. At first she gave a blank stare. Then a light went off in her head. Taking out pencil and paper, she did some arithmetic and, without any further ado, handed over the fries.

My friend drove away puzzled. Now fully revived, she began to unravel what had happened. It appeared to her that the workers were involved in a chain of command with a machine at the top. It told them what the prices were, it added them together, it cued them to their duties. They took their orders from a cash register. Only when pressured by a customer did the manager at last realize that she had the power to act of her own accord and, in a flash of recognition, overrode the mechanical spell.

I used to be as optimistic as anyone about technology. Once asked in grade school to draw a picture of what my home would look like when I grew up, I sketched, in crayon, a transparent hemisphere resting on a single pole and a little flying saucer containing me, my wife, and our many kids about to dock at it. There were exactly eight little heads (besides mine and my wifes) peeking over the rim of the craft, all identical and propagated with the help of a fertility drug.

When I reached my early teens, I never failed to watch an episode of Star Trek, and I read almost every piece of science fiction Isaac Asimov wrote. On our familys first cross-country trip, I became ecstatic when we got caught in a traffic jam on the Oakland Bay Bridge. To a midwestern boy, traffic jams were exotic events in which only special people living in modernistic cities took part.

There was always an undertow to my technological infatuation, however, which at first I was loath to acknowledge. On that trip out west, I spent most of the time carsick. A few years later, after returning to the lazy metropolis of Topeka, Kansas, I began to notice anomalies in the mechanical utopia of our modernized household. After we got an automatic dishwasher, the size of the pile of dirty plates on the countertop didnt decrease at all. If anything, it increased. My dad bought one of the first word processors ever made in the hopes of easing the time and effort of writing. He spent so much time with that machine, I almost never saw him again.

In my grade-school years, the neighborhood seemed alive with children out in the street playing stickball and hide-and-seek. But the older I grew, the more deserted the street becameexcept for the cars, of course, which had multiplied over time and made playing out-of-doors more perilous. After supper even the cars went into hibernation; the only signs of life were the faint glows cast by cathode ray tubes on living-room blinds.

I had always been on the bashful side, so I went more or less the way of the trend, retreating as determinedly as everyone else to the altar of TV. But lest I surrender utterly to The Void, I applied myself diligently at the piano, practicing several hours a day. To survive socially in a place dominated by the automobile, of course, you had to drive; so I also made an attempt to earn money to buy a car by working at McDonalds. But soon I saw the futility and the irony: in a town whose borders motor vehicles had pushed to the horizons (with a population of 120,000, Topeka covered 50 square miles), the only sensible way to get to my job was by automobile. Until I could afford one, I had to bike the six-mile round trip on busy roads with no shoulders or sidewalks, and I arrived dripping wet. Had I stayed on, I calculated that, like the other workers, I would be working mostly in order to pay for my transportation to work.