Introduction: Alternative Comedian

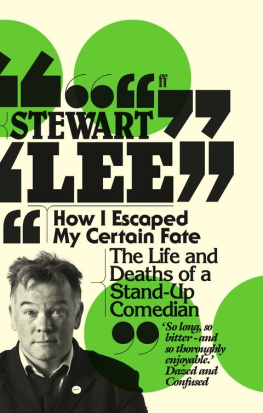

I never wanted to be a comedian. When I was very young I wanted to be a writer, first of all a writer of philosophically inclined thrillers like Robert E. Howard, Ray Bradbury or Stan Lee, and then later a writer of thrillingly inclined philosophy , like Albert Camus, Franz Kafka or Samuel Beckett. But then, at the age of sixteen, I saw a comedian called Ted Chippington open for The Fall in Birmingham in October 1984 and literatures loss became stand-up comedys loss also. However, unlike generations of would-be comedians before me or after me, I never really wanted to be a comedian . I wanted to be an Alternative Comedian, because all other types of comedian were sell-out scum and whores of the system.

The editor of this book worries there might be people perusing this introduction who were born in the eighties, or even the nineties , and who will therefore need help understanding the archaic term Alternative Comedy. I dont think my editor really knows much about the reading habits of young people, and like everyone in publishing, a dying industry with no future, he has his head in the sand. Do they still read at all, the young? I understand from the newspapers that teenagers spend an average of nine hours a week watching internet pornography. Are they supposed to find time to read as well now? Perhaps they are all experts at multitasking. As I understand it is known.

Nonetheless, my editor feels that for many potential readers todays full-spectrum dominance of stand-up comedy across all media, in the form of panel shows, top-selling DVDs, live stadium gigs and cash-in books, might be something they take for granted. It was not ever thus, and apparently some context is necessary else these pages appear as nothing more than the demented ramblings of an inexplicably bitter man.

I started out as a stand-up in the eighties, just as the Alternative Comedy scene that shaped me was coalescing into a commercial entity; by the end of the nineties, I had co-starred in four television series for the BBC and performed over 2,000 stand-up gigs. But by the turn of a new century, all my broadcasting work was cancelled, and Id been circling the stand-up comedy circuit apparently aimlessly for over a decade. So sometime around the back end of 2000 or the start of 2001, I gradually, incrementally and without any fanfare or even much thought gave up being a stand-up comedian. By the time I quit, Alternative Comedy, and the machinery around it, was hardly recognisable from its beginnings in the late seventies anyway. Alternative comedy? said the Bullseye host and old-school comic Jim Bowen every day from 1979 until his tragic end choking to death on a slice of bully beef. Its the alternative to comedy. And it had been, thank God.

I was born in 1968. For my generation of London-circuit stand-up comedians there was a Year Zero attitude to 1979. Holy texts found in a skip out the back of the offices of the London listings magazine Time Out tell us how, with a few incendiary post-punk punchlines, Alexei Sayle, Arnold Brown, Dawn French and Andy de la Tour destroyed the British comedy hegemony of Upper-Class Oxbridge Satirical Songs and Working-Class Bow Tie-Sporting Racism. Then, with the fragments of these smashed idols and their own bare hands, they built the pioneering stand-up clubs The Comedy Store and The Comic Strip. In so doing they founded the egalitarian Polytechnic of Laughs that is todays comedy establishment. Every religion needs a Genesis myth, and this is contemporary British stand-up comedys very own creation story.

In his autobiography I Stole Freddie Mercurys Birthday Cake, the late, great Malcolm Hardee says it was he who first coined the term Alternative in relation to comedy or cabaret, for a night he hosted in a pub called The Ferry Inn in Salcombe in 1978, in order to differentiate it from the more mainstream fare offered by the local yacht club. This is probably the only true fact in Malcolms book.

However, this simplified fable ignores the rather more complex nature of British comedy in the seventies. Its a romantic exaggeration to claim that The Comedy Store had an ideological position. It did, for about a week in 1980, but it didnt when it started and obviously its policy today is defined by commercial imperatives alone. It is true there was an enormous bulk of increasingly dated and dubious workingmens- club comics laughing at Pakistanis, poofs and their wives mothers. Their hot piss regularly cascaded into my childhood home via the conduit of ITVs The Comedians, where enthusiastically dissipated tap-room whimsy and economically compressed racial hatred (the latter dishonestly edited out of the series cosily nostalgic DVD releases) were interspersed with trad jazz tunes from Kenny Ball or Sheps Banjo Boys. Like an iceberg barely visible above the waterline of light entertainment, these twats nevertheless made up the majority of live stand-up in Britain at the time.

Bernard Manning remained the liberal presss chief old-school whipping boy until his death in 2007, largely because he was the only one of these fools anyone could even remember the name of. Personally, I always preferred George Welly Roper .

Meanwhile, the slowly dissipating after-fart of the fifties and sixties Oxbridge satire boom meant that posh kids still helmed the high-profile left-field TV and radio shows, such as Not the Nine OClock News or Radio Active , as they do again today, and got to tour a Cambridge Footlights show to mid-range theatre venues in the south of England every year, still dressed in matching outfits and singing funny songs about the news at the piano.

Of course, there were dozens of superb seventies acts that didnt fit this bipolar model and who were guilty of few, if any, of the ideological crimes now retrospectively ascribed to all British stand-up before 1979. It is difficult to pigeonhole the rarely bettered bone-dry stealth bombs of Dave Allen, the variety-circuit shtick of Les Dawson, the snug-bar surrealism of Chic Murray, the art-house proto-Alternative Comedy of John Dowie, the punk poetry of John Cooper Clarke and the storytelling folk-singer comedians Billy Connolly, Max Boyce, Jasper Carrott and Mike Harding. So, for the sake of simplicity, I will ignore them. (There is probably something on the internet you can read instead.)

Another conveniently ignored factor in the development of the Alternative Comedy scene is economics. For example , when I started on the circuit in London in 1989, Roland and Claire Muldoons CAST organisation was a relatively high-profile promoter of New Variety nights, usually with a textbook balance of performers of all racial and sexual persuasions on the bill. But in the seventies, CAST had been a touring radical theatre group, expressly formed to bring about the collapse of capitalism and to encourage mass drugtaking and compulsory homosexuality, its funding continually questioned in the Commons by the perpetually outraged Tory MP Teddy Taylor. After the Conservative landslide of 1979, the ever-adaptable Muldoons smelt change in the air and scaled down their theatre shows into Alternative Cabaret evenings that espoused the same ideals but didnt rely on funding that was clearly going to disappear. As the comedy historian Oliver Double noted in his study of the early circuit , Alternative Comedy: From Radicalism to Commercialism , refugees from left-wing theatre groups also found themselves key players in early Comedy Store line-ups or shows by Tony Allens Alternative Cabaret collective. There are few forms of entertainment cheaper to stage than stand-up. In some ways the Alternative Comedy scene was initiated on an economic model that was incongruously Thatcherite.