The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imaginationindeed, everything and anything except me.

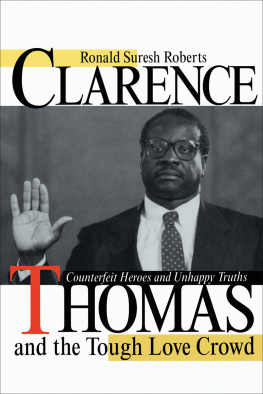

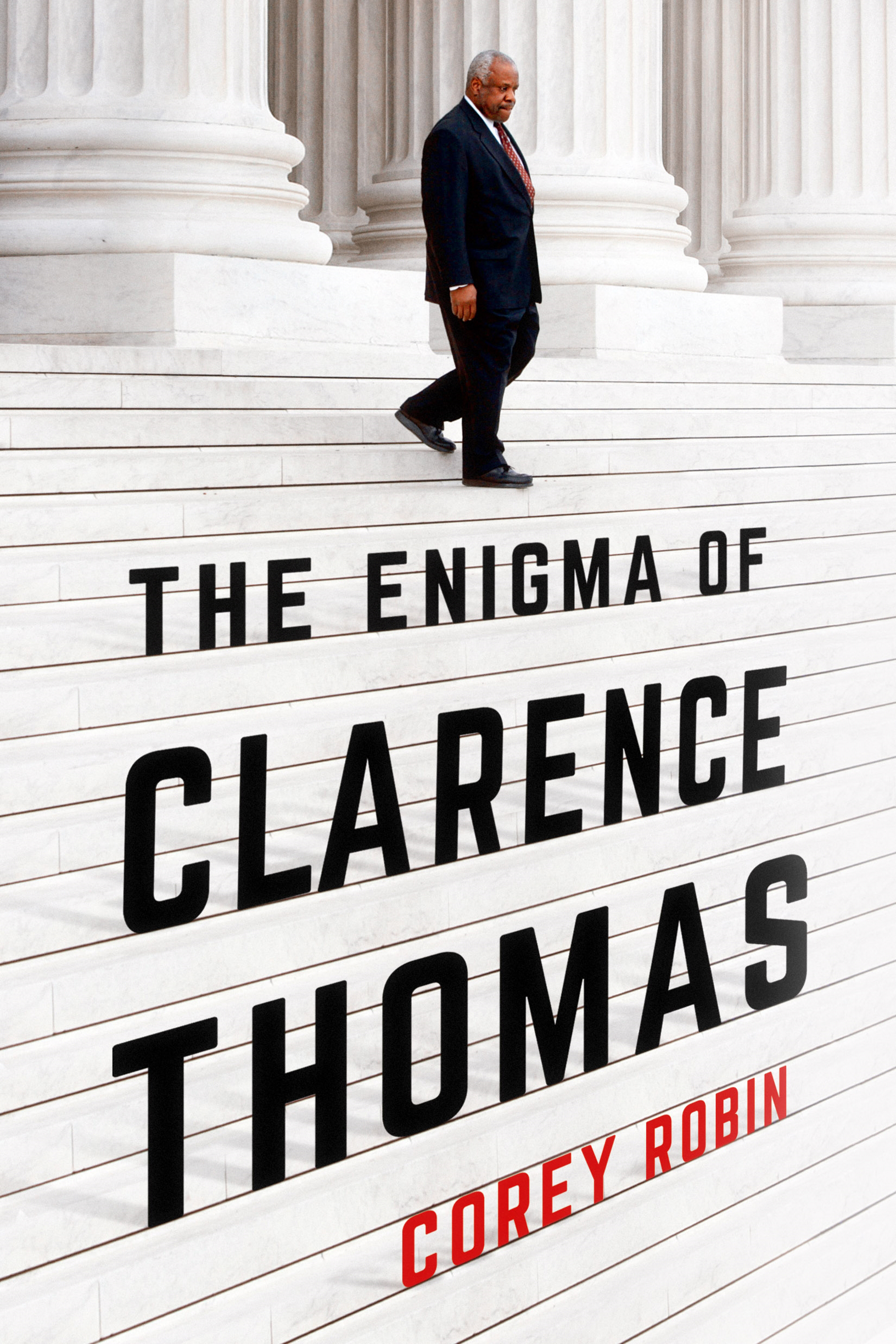

Clarence Thomas is the longest-serving justice on the current Supreme Court. When he joined the Court on October 18, 1991, the Soviet Union was a country, Hillary Clinton was Arkansass First Lady, and Donald Trump was declaring the first of his businesses six bankruptcies.

Ever since he became a candidate for the Court, Thomas has spoken to and for the most revanchist elements of the American right. During his Senate confirmation hearings, his nomination was championed by Republican operative Floyd Brown, who made the notorious Willie Horton ad that helped sink the presidential campaign of Michael Dukakis. After George H. W. Bushs election in 1988, Brown formed a new organization to advocate for Bushs Supreme Court nominees. He called it Citizens United. Throughout the Obama years, Thomas was known as the Tea Party justice. His blistering dissents were welcomed by many in the movement, and his wife, Virginia, worked closely with Tea Party leaders.

With the election of Trump, Thomass influence has grown. Not only has he authored several important opinions in recent yearsabout abortion and the First Amendment, the police and probable causebut his former law clerks also play a leading role in and around the Trump regime.

Thomas is also a black nationalist.

When he was nearly forty years old, just four years shy of his appointment to the Court, Thomas set out the foundations of his political vision in the Atlantic Monthly: There is nothing you can do to get past black skin. I dont care how educated you are, how good you areyoull never have the same contacts or opportunities, youll never be seen as equal to whites. No moments indiscretion, this was the distillation of a lifetime of learning, which began in the segregated precincts of Savannah during the 1950s and continued through his college years in the 1960s. As a militant undergraduate at the College of the Holy Cross, Thomas came into contact with the tenets and practices of black nationalism and Black Power. He devoured the speeches of Malcolm X, which he listened to on records and was still reciting from memory two decades later.

With the conclusion of the 201819 term, Thomas has finished his twenty-eighth year on the Court. At the age of seventy-one, he is far younger than Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, who are eighty-six and eighty, respectively, and Anthony Kennedy, who retired in 2018 at the age of eighty-two. Should Thomas remain on the Court another nine years, he will be the longest-serving justice in the history of the United States. His imprint will be broad and deep. Despite that, the only things most Americans know about him are that he once was accused of sexual harassment and that he almost never speaks from the bench.

IN THE 3,300-PAGE transcript of Thomass Senate confirmation hearings, the word enigma appears thirty times.

But once Anita Hill stepped forward with credible allegations that Thomas had sexually harassed her, and Thomas denied them, and other women stepped forward with additional credible allegations of sexual harassment, it was obvious to everyone but his most hard-bitten defenders that Thomas would say anything to get his seat on the Court. Artful dissembling, if not outright lies, is what we have come to expect from our Supreme Court nominees.

Yet the enigma of Clarence Thomas remains.

Thomas is not a conservative man who happens to be black. Thomas is a black man whose conservatism is overwhelmingly defined by and oriented toward the interests of black people, as he understands them. In popular and academic discussion, African American concerns are associated with liberalism and the left. The same is true in discussions of the Court: liberals stand for civil rights and voting rights; conservatives oppose them. Yet Thomas has long been committed to a conservatism that speaks to and for African Americans. In a 1987 speech to the Heritage Foundation that was widely shared at the time of his nomination, Thomas claimed that a principled conservatism should make it clear to blacks that conservatives are not hostile to their interests but aggressively supportive of their interests. Such a conservatism would appeal to African Americans not by ignoring race but by breaking the lefts stranglehold on African American allegiances and issues. If you could get the whole racial issue out of the context of liberal and conservative, he said in an interview, most black people would see that they are really conservative.

This race-conscious conservatism is not just a theory for Thomas. It is a politics, a set of values and beliefs, policies and prescriptions, that he has long hoped to cultivate in the black community. He talked about changing the way our people thought, says a close friend of his during the 1970s. That was a clear dream. He talked about a time when we would not be so foolish to be enslaved by just one particular view, or leaders who were clearly captured by one political party. According to Thomas, I saw the prospects of proselytizing many young blacks who, like myself, had been disenchanted with the left; disenchanted with so-called black leaders; and discouraged by the inability to effect change or in any way influence the thinking of black leaders in the Democratic party.

Thomas is the first to recognize that forging a black conservatism, breaking the links between African Americans, liberalism, and Democrats, is a tall order. He knows how unwelcome his views and jurisprudence are in the black community: It pains me deeply, more deeply than any of you can imagine, to be perceived by so many members of my race as doing them harm.

In pursuit of this project, Thomas has benefited enormously from his immersion in black nationalism. Such a claim may seem improbable to readers for whom black nationalism is associated with Third World internationalism and the romance of revolution, notions that Thomas roundly rejects. Like most ideological commitments, Thomass black nationalism is selective. Still, many elements of the program he embraced in the 1960s and 1970sthe celebration of black self-sufficiency, the scathing attack on integration, the support for racial separatism and black institutions, the emphasis on black manhood as the pathway to black freedom, the reverence for black self-defenseremain vital parts of his jurisprudence today.

Thomass black nationalist conservatism is not a pose or a posture. Its rooted in the deepest traditions of African American political thought. In both black conservatism and black nationalism, there is a suspicion of white liberalism and its African American allies, skepticism of the state, pessimism about integration, a focus on the family, an emphasis on traditional morality, an appreciation of black business, and a belief in the saving power of black men. While the two traditions are by no means identical, they overlap in multiple respects. That is why Thomas has been able to forgo the left for the right without having to give up the black nationalism that can be found on either side of the spectrum.