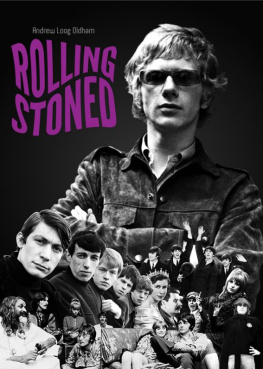

Although I chose not to interview any artists expressly for Fried & Justified , I did draw from interviews, email exchanges and conversations down the years with Mickey Bradley, Damian ONeill, John ONeill, Ian McCulloch, Will Sergeant, Les Pattinson, Julian Cope, David Balfe, Bill Drummond, Jimmy Cauty, Lawrence, David Gedge, Bobby Gillespie, Lee Ranaldo, Euros Childs, Andrew Oldham and Dee Dee Ramone.

Except where sources are credited in the text, all other quotes are taken from my own interviews and encounters.

Thanks to Max Bell, Jane Burridge, Keith Cameron, Andy Ferguson, David Gedge, Ian Harrison, Paul McNally, Louise Nevill, Andrew Oldham, James Oldham, John Reed, Slim Smith, Terry Staunton and, last but not least, Stuart Batsford for his unfailing help and encouragement.

At Faber & Faber Id like to thank Dan Papps, Paul Baillie-Lane, Ian Bahrami and especially Lee Brackstone for his support and reassurance and for helping to clear a path through the trees. Im indebted to Dave Watkins for guiding me through the commissioning stages and making this book happen.

Special thanks to Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty.

During the years Fried & Justified covers I worked with five assistants. They dont feature anywhere near enough in this narrative, but we shared a lot of experiences that Id like to think were mostly enjoyable; they also got my back on plenty of occasions. So in chronological order and without whom Id like to thank Geraldine Oakley, who brought order to the chaos of setting up Brassneck Publicity in 1980; Mel Bell, who took over for much of the rest of the 1980s; Pam Young, who came on board for eighteen months in 1990, and Louise Nevill, who followed her. Sara Lawrence joined me in 1995. She stuck around for a good ten years before she left, but then we got married instead. So there are some happy endings. Id never have finished this book without her love and understanding.

And, belatedly, Im grateful to my family. During my mum and dads lifetime they never understood what I did for a living, yet they were responsible for igniting my passion for pop music in the first place because we had a pile of old 78s at home that were my favourite toys. Id sprawl on the floor of the living room in front of our hefty gramophone and pretend to be a disc jockey. It was a terrible collection of schmaltzy ballads and novelty hits by the likes of David Whitfield, Mantovani, Dickie Valentine, Ruby Murray, Russ Conway and Winifred Atwell, but sometime in 1956 my dad came home with Bill Haley and the Comets Rock Around the Clock LP. I was six years old, but after hearing its rim-shot percussion, driving slap-bass and frantic guitar solos and puzzling over the language of mysteriously titled songs such as Razzle-Dazzle, Rock-a-Beatin Boogie and Shake, Rattle and Roll nothing was the same again. Then, over the next couple of years, my elder sisters Beryl and Sheila began buying singles. Showing remarkably good taste for an eight-year-old, it was the new 45s by Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers and Buddy Holly Id play the most. I was gone real gone, and I was never coming back.

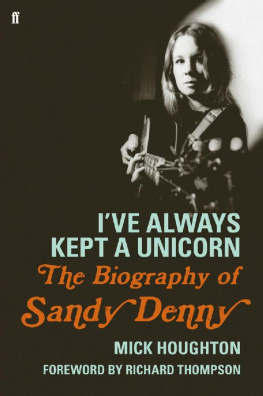

Mick Houghton

November 2018

FOREWORD:

BILLY FURY VERSUS THE WORLD

There are secret histories in pop music.

There is one particular secret history that holds that pop music in Liverpool went straight from Billy Fury singing Halfway to Paradise in 1961 to the release on Zoo Records of Sleeping Gas by the Teardrop Explodes in February 1979, with nothing happening in the intervening eighteen years.

This secret history of pop music can only be glanced at from time to time, and then only by those with gifted vision.

There are those who say, What about Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, or the Real Thing, or even Deaf School? It is best not to listen to those people their vision is not to be trusted.

I am pleased to note here that Zoo Records was ours.

The founder of Sire Records was Seymour Stein. He was from New York, and thus had never heard of Billy Fury. But I suspected he shared a parallel secret history of pop music, one in which nothing had happened in American rock between Del Shannons Runaway dropping out of the Billboard Hot 100 in 1961 and the release on Sire Records of Blitzkrieg Bop by the Ramones in February 1976.

Come the summer of 79, Seymour Stein was interested in signing one of our other Zoo Records bands Echo & the Bunnymen to his Sire Records. We sensed Sire Records might be a good place for Echo & the Bunnymen to explore the possibility of developing other channels in future secret histories of pop music.

Stein was over from New York. We headed down from Liverpool to the Sire Records London office. This was round the back of the then derelict Covent Garden market.

One of the people who Stein introduced us to was a man in his late twenties. As in a couple of years older than me. This man so mumbled his name, I wasnt too sure what it was. I was told he was a press officer and we might be working with him. I assumed a press officer would be the person in the record company who oversaw the pressing of the records. As far as I knew, the main job of a record company was to press records. Bands wrote, played and recorded the songs, record companies pressed those recordings into records, record shops sold the records to people who wanted to play the records at home.

But I was wrong on numerous fronts: mainly about how the record industry worked, but more precisely about what a press officer did. It seemed this mans job had nothing to do with the pressing of records. His job was to put one of each of the newly pressed and soon-to-be-released records into an envelope, seal the envelope, write the address of a music paper on the front of the envelope, stick a stamp on the envelope and finally drop the envelope into a pillar box. At the time there were four music papers in the UK: the Melody Maker, New Musical Express, Sounds and Record Mirror . At most, this job would take thirty minutes per newly released record. I did not see how this could amount to a proper full-time job. With the records we had been releasing on Zoo, that is exactly what we did. And a week or so later the record in question would be reviewed as Single of the Week in at least three of those four music papers.

But this man I was introduced to in the Sire office seemed affable enough, and we were soon discussing the merits of the Flying Burrito Brothers version of The Dark End of the Street, compared to the original by James Carr. He then asked me if I had recently listened to The Sound of Fury by Billy Fury. This was code. It was then I knew I was talking with a man who had a gifted vision regarding the secret history of pop music.

This man began to turn up at Echo & the Bunnymen and Teardrop Explodes gigs, always unannounced and usually with some music journalist in tow.

And as I became more aware of what his job was, or what it was supposed to be, I began to question his methods. If he was supposed to be convincing the journalist in tow how great the Teardrop Explodes were, why was he talking to the journalist only about the merits of Gram Parsonss second album?

And when Echo & the Bunnymen released their second album, why would I overhear him telling the journalist in tow that this second album was not as good as their first album?

But then a couple of weeks later there would be a five-star rave review of Echo & the Bunnymens second album by the said journalist in tow.