M. S. Subbulakshmi

A portrait of MS.

(Ink on paper, Manohar Devadoss, 2002)

ALSO BY T. J. S. GEORGE

Krishna Menon: A Biography

Lee Kuan Yews Singapore

The Life and Times of Nargis

The Goenka Letters: Behind the Scenes in the Indian Express

Editing: A Handbook for Journalists

The Provincial Press in India

Revolt in Mindanao: Rise of Islam in Philippine Politics

The First Refuge of Scoundrels: Politics in Modern India

Lessons in Journalism: The Story of Pothan Joseph

The Enquire Dictionary of Quotations

The Enquire Dictionary: Ideas, Issues, Innovations

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm

promoted by Rupa Publications India

First published in India in 2016 by

Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Copyright T. J. S. George 2004, 2016

All rights reserved.

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by him/her which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain permission, this has not been possible in all cases; any omissions brought to our attention will be remedied in future editions.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from Aleph Book Company.

eISBN:978-93-84067-83-0

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

To

A Trinity, in homage

In the course of this study three powerful personalities came through

the records as exemplars of its running themesan exploited castes

yearning for dignity and women musicians struggle for equality.

In strength of character, in self-esteem, in scale of aesthetic attainment,

no one in the twentieth-century Carnatic firmament surpassed

Veena Dhanam, vocalist Bangalore Nagarathnamma and dancer

Balasaraswathi. This book is dedicated to these indomitable artistes,

a Trinity in themselves, in respectful admiration.

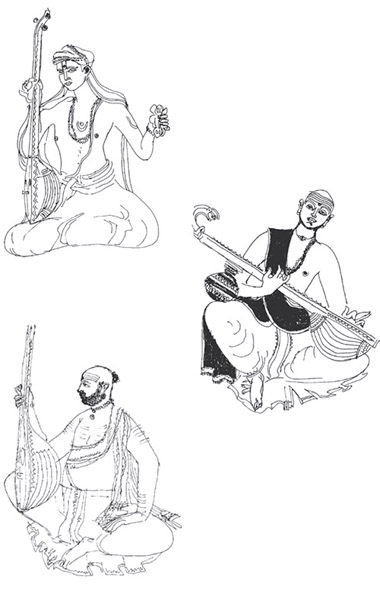

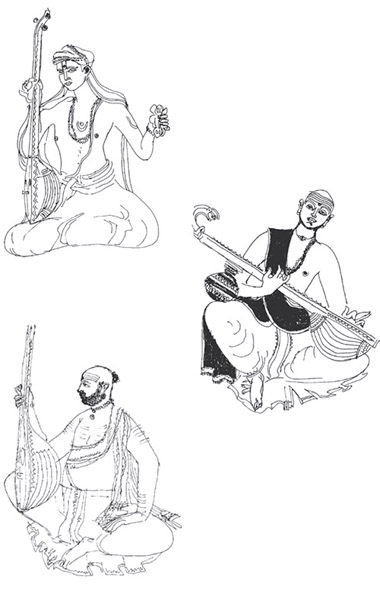

Thiagaraja

Muthuswamy Dikshitar

Shyama Shastri

The Carnatic Trinity.

(Ink on paper, Nambudiri)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

RISE OF THE NEW-GEN

There was unease in the citadel when a study of M. S. Subbulakshmi was published in 2004 by an outsider who bore a name given to him by his Christian parents. That I was not brought up on Tamil soil was further ground for suspicion. Forgiveness arrived soon enough, and a measure of appreciation, but the initial reservations were a pointer to the sectarian sentiments that ruled the world of Carnatic music not so long ago. Religion and language posed no problems for M. S. Subbulakshmi but her social background made her a victim of prejudice when she broke into the musical firmament as a child prodigy in the early twentieth century. Given the pulls of tradition in Indias conservative milieu, it is no surprise that the prejudices and controversies that prevailed a hundred years ago are still alive. A new generation of artistes has come up demanding democratization, in music as in political life. So have new trends in listener aptitudes and expectations. The culture of Carnatic music is beset by challenges that make the present excitingand the future variable.

The music itself etched a narrative of unbroken glory from the sixteenth century when Purandara Dasa laid the foundations of the worlds most rigorously mathematical musical structure. Two centuries later the Classical Age dawned when three geniuses, the Carnatic Trinity, were born in the same village contemporaneously. The standards set by Thiagaraja, Muthuswamy Dikshitar and Shyama Shastri led to the celebratory years of Carnatic music, the Golden Age of the twentieth century. Such was the proliferation of talent during this period that it saw two different sets of Trinities among women performers alonethe courageous ladies to whom this book is dedicated and the beloved M. S. Subbulakshmi, D. K. Pattammal and M. L. Vasanthakumari. The Modern Age followed, like an extension of the Golden Age, with exquisite performers who became household names. Straddling the twentieth and twenty-first century came the New-Gen, a talented group of educated men and women doing justice to the Carnatic heritage but on their terms. They are all around us, inspiring and intimidating at once, comfortable with their ways and unafraid of being different. Sanjay Subrahmanyan, P. Unnikrishnan and Abhishek Raghuram are just a few of them. If one name has to be singled out of this fraternity, it will have to be T. M. Krishna, singer, scholar, and iconoclast rolled into one. Among the issues he forced into the public domain were those that haunted M. S. Subbulakshmi when she cut her first record at age ten.

The vexatious problems then were upper-caste disapproval of lower-caste artistes and male objection to female singers. MS overcame both thanks to her superior musicality and her husbands adroit management of her Sanskritization. But the problems did not go away. T. M. Krishna was not born when M. S. Subbulakshmis Meera was released (1945) or when the first New-Gen revolution brought on Flower Children and the Summer of Love (1967). Nearly a decade passed and Indira Gandhi was six months into her Emergency rule when he arrived. But there he was describing Carnatic music as a Brahmin-dominated male chauvinistic world that needed social re-engineering. Some things never change.

Krishna could not be lightly dismissed. Not only was he part of the 2.75 per cent Brahmin community in Tamil Nadu; his actions backed his words. He withdrew from the almost century-old margazhi season of music in Madras to protest against discrimination in the arts. When the kutcheris were going on in the prestigious sabha halls in the city, he held a concert on the beach for the benefit of fisherfolk.

Some of Krishnas arguments may indeed be overstated. Perhaps the Tamil Brahmin dominance is only at the establishment level while at the level of the art non-Tamils and non-Brahmins have soared high on merit. His opposition to the very term classical, which he decries as too elitist, is specious; it is a privilege of all art and all literature that there is a categorization called classical that holds up the ideals to aspire to. But he does have a case when he attacks the creation of socio-religious requirements for the appreciation or learning of music and argues that Carnatic music should not be a quasi-religious Hindu experience.

No quasi-religious lines are drawn in Hindustani music (because of, or in spite of, Muslim influence, depending on the angle of vision). The popularity of North Indian music has been on the rise in the south according to some aficionados. Such a trend is certainly visible in Karnataka; where Purandara Dasa once laboured on the Carnatic grammar, Bhimsen Joshi and Gangubai Hangal spread the magic of Hindustani music. If the magic continues, one reason is that the northern tradition is relatively easy to access. The southern system is so rigorous that the best leave no disciples. Veena Dhanammal, the quintessence of Carnatic purity, has no one trying to continue her bani, her style. Nor has Balasaraswathi or Bangalore Nagarathnamma. Modern masters from Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavathar to G. N. Balasubramanyam are best enjoyed by experienced and knowledgeable listeners whose numbers, not inexplicably, are dwindling. M. S. Subbulakshmi is the only Carnatic singer whose mass appeal has not seen any dip; it has in fact been rising if sales of her Suprabhatham are any indication.