Table of Contents

S

19201983

D R R

19161989

Contents

T HERE can be a problem with Indian names written in English. All proper nouns have been used, insofar as can be established, as they have been conventionally spelt. Kalki R. Krishnamurthi and J. Krishnamurti had the same given name, spelt differently in English. This is true of other names as well. Viswanathan, Vishwanathan and Visvanathan are the same name, spelt differently, as are Subrahmanyam, Subramaniam and Subramanian. The name Subbulakshmi itself is often written as Subbalakshmi or Subbulaxmi. Likewise, Shanmukhavadivu could be, and often is, written as Shanmugavadivu, with no significant loss of meaning. This is to do with transliteration from the Tamil.

Some names are written in English in a manner which seems elegant to me. For instance, I have used Carnatic instead of Karnatic, Karnatik or Karnatak, though I will admit that I would write karnataka sangeetam. I also write Minakshi though the name is often written as Meenakshi. Subbulakshmis film is always Sakuntalai though I have written the name as Shakuntala when referring to the character. Likewise, Mira, though the film is always Meera.

The trinity have had their names spelt in a variety of ways. Tyagaraja has been called Thyagaraja, Thiagaraja and Thyagarajar, and in moments of rapture, Iyer-val. Syama Sastri has been Shyama Sastri and Shyama Shastri and Muthusvami Dikshitar has been Muttuswami Dikshitar, Muddusvami Dikshitar, Muthuswami Dikshithar and sometimes Muthusvami Diksita. I have used Tyagaraja, Syama Sastri and Muthusvami Dikshitar. I have used Svati Tirunal but he could also become Swati, or Swathi, Thirunal.

Some famous musicians, and persons well known in public life, and especially in south India, are often referred to by their initials. Thus, MS, GNB and MLV. Others were always referred to by one distinctive part of their full names. Hence Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavathar, Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar, Musiri Subramania Iyer, Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer and Lalgudi G. Jayaraman. R. Krishnamurthi, founder and editor of Kalki, was likewise always Kalki. Sometimes honorifics become part of a person's name. T. Dhanam can be T. Dhanammal, simply Dhanammal or 'Vina' Dhanammal. Subbulakshmi herself was called Kunja in her mother's home, Kunjakka by younger members of her husband's home and Kunjamma by close friends.

In transcribing names of songs and ragas, I have not used diacritical marks. Thus, Sankarabharanam instead of amkarbharaNa, Shanmukhapriya instead of aNmukhpriya and Hiranmayim Lakshmim instead of hiraNmaym laksmm. Most references to songs are in the Opening words of song/Raga format, such as Tulasi jagajjanani/Saveri or Vara Narada/Vijayasri.

Some words in Indian languages are now so commonly used that I have not used italics: bhakti, bhajan, devadasi, mrdangam, ghatam and raga. I have, however, used italics for ragam-tanam-pallavi, neraval, svara, abhang, kirtana, kriti and other purely musical terms. All these terms are explained in the Glossary.

The cities of Chennai, Mumbai and Kolkata have been referred to as Madras, Bombay and Calcutta if the reference in the text relates to a time before the name was changed.

There are many titles awarded to musicians and composers, and these are often used while referring to them. Readers will find the title Sangitha Kalanidhi recurring frequently, the title awarded by The Music Academy, Madras, at Chennai every year to the president of the annual conference and concerts. I have used the spelling Sangitha because that is what the Music Academy uses; the word could be, and is, spelt also as Sangeeta, Sangeetha or Sangita.

O Sarasvati, beautiful and young, with eternal youth, thou who art seated upon a lotus flower, work good for us!

(Opening words of Muthusvami Dikshitars composition Kalavati in the raga Kalavati)

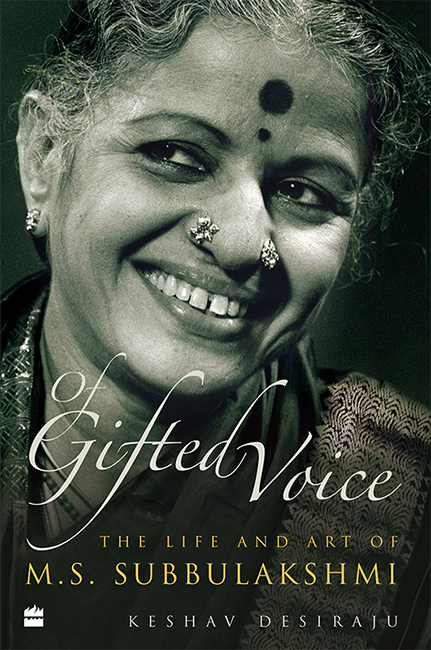

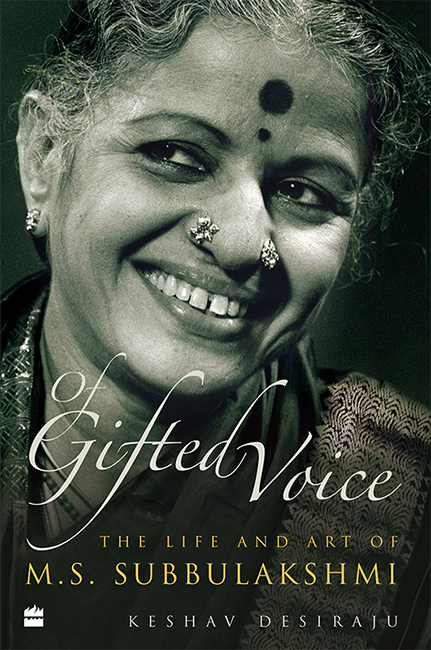

A LL lives are a mixture of character and destiny but it is only in some lives that character is so sharply etched and in which destiny plays so dramatic a role as to make the life itself immortal. M.S. Subbulakshmi is one of these immortals.

M.S. Subbulakshmi has been portrayed in various ways, as a musician who sought and achieved an all-India appeal, as a philanthropist and benefactor of noble causes, as an icon of high south Indian style, as a woman of piety and devotion, and as a friend and associate of the good and the great. But while she was all of these, she was first and foremost a classical musician of the highest order, and it is as such that her lifes work must be assessed. And after all these years, despite her saintly persona and many avatars, it is the music by which we remember her. This is true as well of Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer (19082003), but these two pre-eminent Carnatic musicians, over their very long performing careers, stayed within the bounds of the course they set for themselves early on. This was not the case with Subbulakshmi.

It was a life lived in the public glare; it was a life whose most private moments were carefully obliterated. In her very last years, in a private conversation with an acquaintance, she observed, I do not wish to speak untruths but much of the truth of my life is better unsaid. And in each of these roles, she was nothing but utterly true. If she completely absorbed the Tamil Brahmin ethic in her manner and style, a trait for which she is now mocked by some, she was, to others such as the poet Hoshang Merchant, Mira personified.

You have bodied ecstasy,

Who will find the singer in the song

Or ever sift you from the seer?

Subbulakshmis was a life of extraordinary achievement, especially so for a woman of her times. She was without formal education and without resources and identified by society only as belonging to the devadasi, or courtesan, tradition, but she had unimaginable talent and iron determination. It is widely held that she was an uncommonly modest woman, who rarely expressed an opinion and was easily led, but there is equally no doubt that she knew what she had and had the ambition to achieve what she wanted.

For all her attainments, Subbulakshmi never regarded herself as a feminist icon of any sort. In a foreword to a book of translations of the saint-poet Mira, she observed, very conservatively, At a time when so much is said about the liberation of women the world over, it is good to think of a woman whose soul wanted to liberate itself and merge with the Lord. She always purveyed the impression of traditional conservatism, and insofar as she ever expressed herself on the subject, she was generally of the view that the enormous ability and power of women, strishakti, needed to be curbed and kept in control, preferably by men.

For all the magnificence of her art, we still have no real idea of the person. From a shadowy childhood and tumultuous youth, Subbulakshmi grew into a phenomenon. Recent biographies have followed the standard version, of a powerful voice which shone briefly in films and then surrendered itself to devotional worship and to the cause of the nation; but it is hard not to conclude that the creation of the phenomenon, which transformed a tradition and exalted an art, did not in the process also lead to the snuffing out of a personality, of a spirit and of an extraordinary presence. This is clearly the stuff of tragedy.