Contents

Guide

ALSO BY KRISTIN KIMBALL

The Dirty Life

Scribner

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2019 by Kristin Kimball

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition October 2019

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

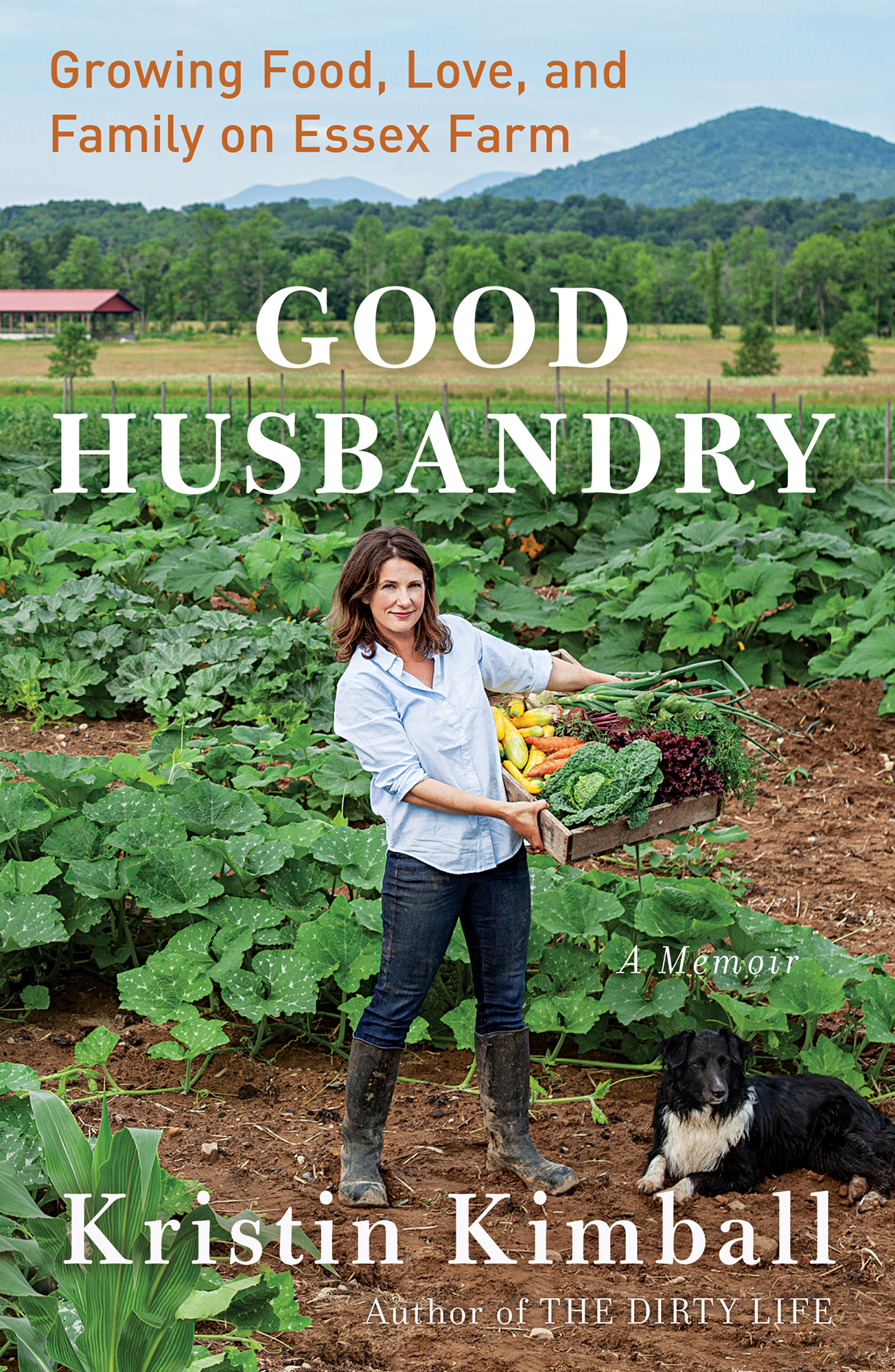

Jacket design by Jaya Miceli

Jacket photograph and author photograph by Ben Stechschulte

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kimball, Kristin, author.

Title: Good husbandry : growing food, love, and family on Essex farm /

Kristin Kimball.

Description: New York : Scribner, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019014660 (print) | LCCN 2019017847 (ebook) | ISBN

9781501111662 (eBook) | ISBN 9781508298328 (eAudio) | ISBN 9781501111532

(hardcover) | ISBN 9781501111655 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Kimball, Kristin. | Essex Farm. | Farm lifeNew York

(State)North Country. | FarmersNew York (State)North

CountryBiography.

Classification: LCC S521.5.N7 (ebook) | LCC S521.5.N7 K56 2019 (print) | DDC

630.9747dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019014660

ISBN 978-1-5011-1153-2

ISBN 978-1-5011-1166-2 (ebook)

Photo Credits: Tara Derr Darling

Eating Poetry from Selected Poems by Mark Strand, copyright 1979, 1980 by Mark Strand. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

For Kelly

PROLOGUE

S ome people say farming is the most wholesome job in the universe. I say having a farm is more like having a gambling problem. A farm is a living, breathing slot machine, doling out just enough reward at exactly the right moment to keep you coming back for more. Farmers are professional hopers, wafting supplication toward ancient gods we dont believe in. We hope in order to ward off disease and accident; or for rain, but not too much; or no rain, but not for too long. If frost threatens early in the fall or late in the spring, we double down on hope, trying to generate with it the degree or two of heat that is the difference between death and another few weeks of life, between a good harvest and none at all. When we win these bets, its magic, like making something out of nothing. When we lose, the chips that get swept off the table can be measured in both love and money.

I figured this out one planting season. The fields were so dry, the wind picked up topsoil and spun it into devils that danced around us as we dug our hands beneath the surface, feeling for moisture. My husband, Mark, and I had built a new greenhouse at the end of winter, and there were tens of thousands of plants inside itwinter squash, cucumbers, brussels sprouts, and tomatoes, straining against the limit of their blocks of soil. It was time for transplanting, but the ground was too dry. The young roots that had developed under the ideal conditions of the greenhouse, with just enough moisture, just enough heat, would confront the real world of the field, which had dried to inhospitable dust. The tender roots would be sucked dry, and the young healthy plants would wilt and die. We had to wait for rain to come and water the soil.

A lot of work had been put into those little plants already. Each one started as a single seed, placed from palms with fingers into two-inch blocks of black potting soil which had been formed by hand with a special toola spring-loaded metal form, on the end of a long handle that was slammed into a pile of damp soil, to make compacted bricks of fertile earth. The rectangle of bricks was then released, gently, into a wooden tray. When the moisture of the soil and the force of the tool were just right, the blocks would hold their shape, with a small dent on the top to hold the seed. The seeds got a sprinkle of soil, and a watering, which would begin to wake them from their sleep.

Wed carried the heavy trays to the germination chamber, an old walk-in cooler scavenged from a restaurant that was going out of business. The chamber had a heater in it, to maintain the warm, even temperature that seeds like best in order to germinate. The flats were stacked one on top of another, six high, on open shelves. It was dark inside the chamber, and humid, and when you opened the bulky door, it smelled like the loamy floor of a forest on a hot summer day. You had to pry the flats apart and shine a headlamp across each of them to see if they had sprouted, and as soon as a few minuscule sprouts were visible, out it came, quickly, to the greenhouse. Most seeds dont need light. They carry enough energy to propel their roots down and the first leaves up. But then the energy of the seed is spent. If they are left in the dark chamber, they start searching for life-giving light, speeding up toward a nonexistent sun. In a matter of hours after germination, they will etiolate into pale, spindly, weak things that might be coaxed to live for a while by a dose of light but will never make good, and will have to be thrown into the compost pile.

Once in the greenhouse, the seedlings were painstakingly cared for every day for weeks, their soil kept moist, the temperature moderate. We woke up on cold nights to make sure the propane heaters were burning, and came rushing in from the barn on sunny afternoons to open vents and roll up the plastic walls. All this care and diligence was spent, weeks of work and many tons of expensive materials, because these plants represented a good part of a years worth of food for two hundred people who counted on us to grow it for them.

We started Essex Farm from scratch together, not long after we met, a year before we got married. Mark was at the very edge of this wave we are still riding, made up of ambitious young farmers who grow food to sell directly to a market that is interested in how and where it comes from.

When I met him, I was thirty-one and working as a freelance writer in New York City. He was running a vegetable farm in Pennsylvania. We were not an obvious match, but we fell for each other, clicked together like a pair of magnets. He left the farm in Pennsylvania, I left my apartment in the East Village. We moved to a neglected five hundred acres in the Adirondack Park, on the rural northeastern edge of New York State, and dug in.

The farm we built was a sprawling, diversified, bewitchingly beautiful thing, composed of innumerable living parts, sometimes working in perfect synergy, sometimes descending into chaos. We created it around our desire to produce all the food we needed for an interesting, healthy, delicious diet, and to try to do it sustainably, all from one piece of land that wed come to know as intimately as wed come to know each other. It was a radical undertaking. That we thought creating such a diverse farm was possible was a matter, on Marks part, of ambition and extreme optimism; and on mine, at that time, of ignorance and inexperience. I didnt know enough about farming to be afraid of it.