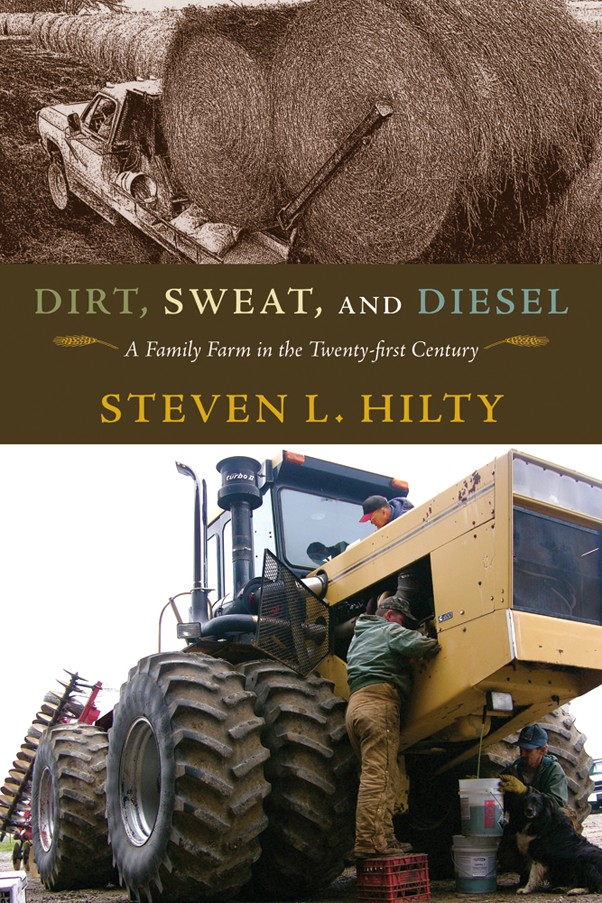

Copyright 2016 by Steven L. Hilty

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65211

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved. First printing, 2016.

ISBN: 978-0-8262-2079-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015960092

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Typeface: Jenson

ISBN-13: 978-0-8262-7357-4 (electronic)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All of the conversations and events in this book, and the descriptions of the land, people, farm life, and wildlife are real. They were obtained while working and visiting with the Montgomery family (not their real name) on their farm in western Missouri. Activities and conversations were recorded in notebooks on the spot or as soon thereafter as possible. In a few cases notes were dictated onto a minicassette recorder. Many events were photographed to preserve details for later descriptions. To protect privacy, the real names of people, including, neighbors, business associates and friends, however brief their appearance, have been changed. Most geographical and businesses names have been changed although real names have been retained for larger cities. I am deeply indebted to the families portrayed here for their hospitality and generosity, and for opening their homes and lives to me. They were unfailingly gracious, often going out of their way to teach me what I needed to know, to show me aspects of farming and community affairs that they felt were important and, through it all, went about their daily work unmindful that I was looking over their shoulders. Without their cooperation this book would not have been possible.

I also thank Harlan (not his real name), the familys full-time farm employee, for sharing many personal aspects of his life with humor and candor, as well as the many anonymous persons who appear in this book. They are uncelebrated heroes too, real people who live in the community and whose lives and work and personalities enrich us all.

This manuscript benefited greatly from the comments of two anonymous readers. Thanks also are extended to Joanne Asala, who edited the manuscript, and to the staff of the University of Missouri Press, including especially Gary A. Kass, Deanna Davis, Stephanie Williams, and David Rosenbaum, as well as others at the press whose efforts, in various ways, helped to see this manuscript through to publication.

A Missouri Department of Conservation Natural Events Calendar was helpful in placing plant flowering and fruiting events and various wildlife activities in appropriate time sequences during the year.

Lastly, I thank my daughter Dru for encouraging this project after a college project piqued her interest in family farms, for reading and commenting on numerous chapters and for her insightful suggestions regarding a title. I also thank my daughter LaRae for accompanying me on several farm trips.

My greatest debt is to my wife Beverly, who read and commented on all of the chapters, some of them repeatedly, provided a stream of ideas and fresh perspectives, examined photos and illustrative material, and was always supportive.

I grew up on a family farm in Missouri but left to pursue another career. However, over the years, my family and I returned many times to this farm and continue to do so. This book is, in many ways, a product of my love of farming and farm life instilled in me by my parents.

INTRODUCTION

Once, more than three quarters of the American population counted themselves as rural, raising their families and earning their livelihoods on small family farms. They were part of a nation built on agriculture. Today, less than five percent of the population is rural, and less than one percent wrests a living from the land. In the last few decades, there has been renewed interest in rural life and, in some areas, rural populations have increased, but these people are mostly urban dwellers with urban jobs who have sought a less-stressful life in rural settings. In general, their livelihoods dont come entirely from the land, and it makes a difference. Those who depend on the land for their living, who roll their dice with weather and pestilence and uncertain commodity prices, see rural life differently than those who dont.

This is an account of the activities of a western Missouri farm family. It is a father and son partnership involving two households that live and work together. One wife works off the farm, the other worked off the farm part time for a few years. In both families incomes are derived almost entirely from the land they own and rent. Their farming business is varied and complex. The land they farm, about eighty-five percent of it rented, fed and clothed nine families a generation ago, and more than twice that many families two or three generations ago. Their farm operation continues to grow, as seems inevitable if family farms hope to survive in the increasingly tumultuous world of modern agribusiness. The men overcome a daunting and ever-changing array of technological hurdles in their daily business. They are not paid by the hour nor do they measure their financial successes and failures by counting the hours they work. Workdays are often long, but they accept the hours with stoicismthey wouldnt want it otherwise.

Both families are much more closely bound to modern technology than were earlier generations. Not surprisingly, they lack some of the independence that marked earlier rural generations when most meat, milk, vegetables, butter, and other foods were homegrown, and farm work was done with horses and simple equipment. They use computers in some aspects of their business but are not dependent upon them for day-to-day farm decisions. Rather, their success in farming stems more from a store of experience, an astute business acumen combined with frugality, and an intimate knowledge of cattle husbandry, farming basics, and of the mechanics of the machinery they use. They follow cattle, commodity, and farm machinery prices with an intensity that borders on obsession, attend several agriculture trade shows each year, and investigate anything that could potentially make their work easier or their business more profitable. No one requires their participation in these pursuitsit is what they do as successful farmers.

While rural and urban life are more similar today than in the past, some aspects of modern rural life still set it apart from that of most urban environments. Despite the vicarious violence that television and other forms of near-instant communication bring today, most urban dwellers are largely insulated from basic biological lifecycles, and from the connectedness to the land that farmers and ranchers feel. Urban dwellers see clean, well-organized fruit and vegetable displays and packaged meat on a supermarket shelf, milk in a carton, and butter in endless variety. Rural dwellers see the garden and orchard that battles weather and pests, the newborn calf from which the meat derives, and the cow that produces the milk or struggles to birth the calf. They see rats under grain bins, insects in hoppers of fresh-harvested grain, storms that wipe out a seasons crop in minutes, newborn calves that freeze overnight or drown in floods, and sick cows that have to be put down. Cycles of life and death are part of the fabric of farm life, and it may seem that farmers are inured to them, but such cycles are taken in stride without moral judgment or reflection. Some readers may find this difficult to comprehend, and may find a few of the events described upsetting, but farmers generally dont entertain such judgments. Life continues, and those close to these cycles see themselves integrated within them rather than observers or evaluators apart from them.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.