All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Special Collections, College of Charleston Libraries, for permission to quote from the materials held in the Gertrude Legendre collection, and to Stephanie E. Phelan for permission to reprint New Years Sonnet by Larry Phelan.

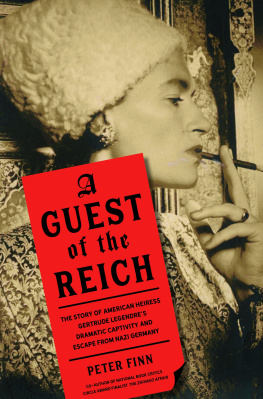

Name: Finn, Peter, [date] author.

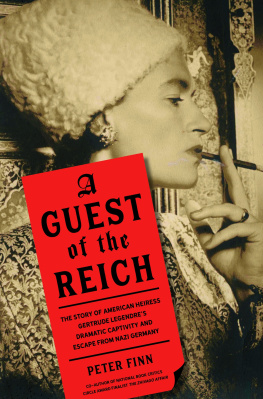

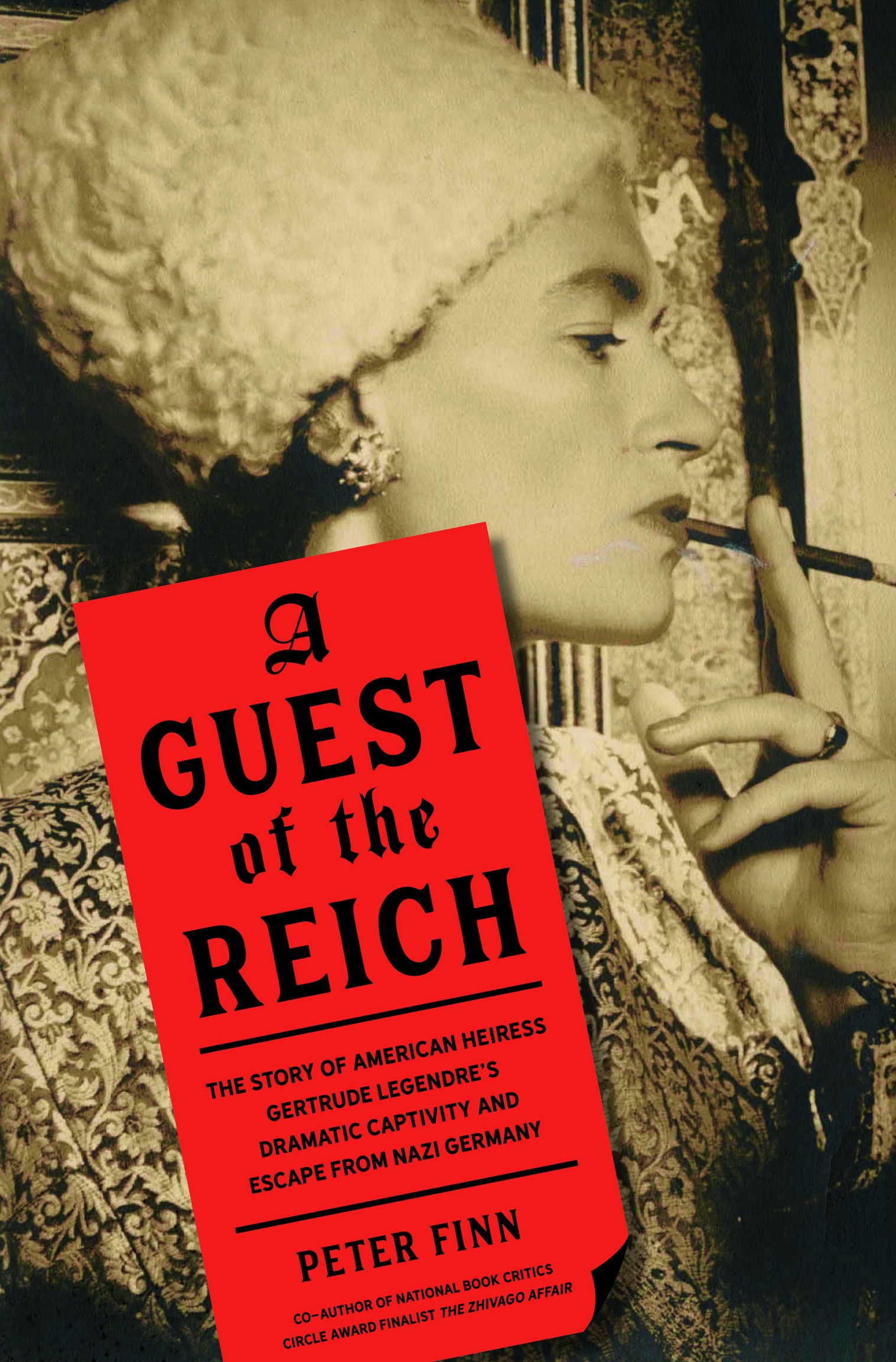

Title: A guest of the Reich : the story of American heiress Gertrude Legendres dramatic captivity and escape from Nazi Germany / Peter Finn.

Description: First edition. New York : Pantheon Books, 2019. Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019002112. ISBN 9781524747336 (hardcover : alk. paper). ISBN 9781524747343 (ebook).

Subjects: LCSH : Legendre, Gertrude Sanford, 19022000. World War, 19391945Secret serviceUnited States. Women spiesUnited StatesBiography. United StatesOffice of Strategic ServicesHistory. Women prisoners of warGermanyBiography. World War, 19391945GermanyPrisoners and prisons. SocialitesUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC D 810. S 8 L 516 2019 | DDC 940.54/7243092 [ B ]dc23 | LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2019002112

Cover photograph of Gertrude Legendre, 1938, by George Platt Lynes. Used with permission of The George Platt Lynes Estate. Print: College of Charleston Special Collections, Charleston, South Carolina

1

Paris

On the afternoon of September 22, 1944, Gertrude Legendre strolled into the bar on the rue Cambon side of the Htel Ritz . Outside the street was lined with U.S. Army jeeps, and inside the place was already crowded, mostly with Americans, a mixture of military officers and war correspondents, their volubility rising amid whorls of cigarette smoke. White-jacketed barmen mixed cocktails behind a dark mahogany counter, and the hotels patrons consumed the signature drinks in clusters around the small tables. Just one month after the city was liberated from the Nazis, this was the Paris a certain kind of American remembered: exclusive and jolly and alcohol-soaked.

The forty-two-year-old Legendreknown all her life as Gertiewas perfectly at ease in the legendary watering hole, a magnet over many years for wealthy Americans and Hollywood stars, as well as assorted European aristocrats, diplomats, spies, oligarchs, and, until recently, Nazi grandees. Field Marshal Hermann Gring had taken over the imperial suite after Paris fell to the Germans.

Gertie knew the head barman, Frank Meier, from previous visits to the Ritz, including a stopover in the winter of 1928, when she was twenty-six and on her way to a big-game hunting expedition in East Africa. Meier, inventor of such cocktails as the bees knees , the royal highball, and the sidecar, was still managing the room in 1944, his eyelids and jowls heavier, but with the same slicked, center-parted hair, groomed mustache, and pince-nez. He had worked in the bar during the occupation but surreptitiously helped the Resistance , ensuring that he kept his position after liberation.

The two reminisced about Gerties prewar stays at the hotel, and she talked about the 192829 hunt in the highlands of Abyssinia. Meier had told Gertie that when she reached Addis Ababa, she should drop in on his friend the head chef to the emperor Haile Selassie; she later dined with the Lion of Judah in his palace and ate a fourteen-course meal, alternating between European and African dishes, off dinner plates encrusted with gold coins. Gertie recalled that the local honey wine, called tej, was especially potent. It went straight to my head like champagne.

In 1944 Paris, Gertie was wearing the uniform of a first lieutenant in the Womens Army Corps (WAC), though, as she was the first to acknowledge, she was no soldier and couldnt salute properly. She did, however, know how to dress. After arriving in the city, she had her khakis tailored by Madame Manon, her longtime dressmaker, who couldnt wait to fit my uniform properly taking it in here, and lifting a bit there. Her helmet, three sizes too big, stayed as is.

I must send you a picture of me in my Khaki. You would be so amused, she wrote to her husband, Sidney, who was serving in Hawaii, a navy lieutenant commander in the intelligence center of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. They had not seen each other for two years and expressed their loveand the distress of being apart so longthrough their almost daily letters. Do you ever cry because you miss me? wrote Gertie. I do so much. I wonder if time is rubbing off the edge and you are now accustomed to the separation. I find it an incurable heartache, and I dont suppose I would want it any other way.

Gertie was a civilian employee of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the U.S. spy agency created in 1942 by President Roosevelt and led by William Wild Bill Donovan, whose charisma and daring transformed what had been a bureaucratic stepchilddespised by the FBI and sections of the brassinto a global organization that won grudging respect from the U.S. military. (J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI, never came around.) By wars end, more than twenty-one thousand men and women would serve in the OSS.

Gertie had until recently headed the cable desk at the London branch, overseeing the distribution of all top secret communications in and out of a building that ran European operations. The office was a key point of contact for the governments in exile in Britain; it ran agents into occupied Europe, managed relations with the prickly British services, which resented the growing independence of the OSS, and formulated plans for operations against the Reich after D-day.

Communications about many of these matters passed through Gerties hands, and she was privy to some of the OSSs most secret plans and personnel. She was an administrator, not a spy, but her position gave her unusual insight into OSS operations and post-invasion planning. London was at the heart of the agencys espionage in Europe, and Gertie sat at the center of all communications about that work, giving her an almost accidental font of knowledge about the war effort.

Now she was among the flocks of Americans descending on Paris to set up shop behind the advancing Allied armies. Everyone entering the European theater of operations fell under General Dwight D. Eisenhowers command, so Gertie, unlike in her previous posting, was required to wear a WAC uniform. In Paris, it carried the mark of the liberator, a feather that had yet to lose its plume among the French. It also got you into U.S. mess halls.

Gertie wasnt classically beautiful, describing herself unkindly as a moon-faced, buxom girl. But she radiated confidence and resolve, and her brown eyes and laughing smile were immediately winning. Her grandfather nicknamed her Spunky, and the moniker captured something essential about the girl, and later the woman, with the sometimes fierce mien. Her face, quicksilver in its expressiveness, could open in sparkling enthusiasm or crease in sour distaste. When she was five or six and her governess swept her hair up in a blue taffeta bow that held a corkscrew curl over her forehead, Gertie cut off the twirl of hair with scissors, infuriating the household.