Copyright Editions Grasset & Fasquelle, 2016

English-language translation copyright 2018 by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

First English-language edition

First published in France in 2016 under the title Enfants de Nazis

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or arcade@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Crasnianski, Tania, author.

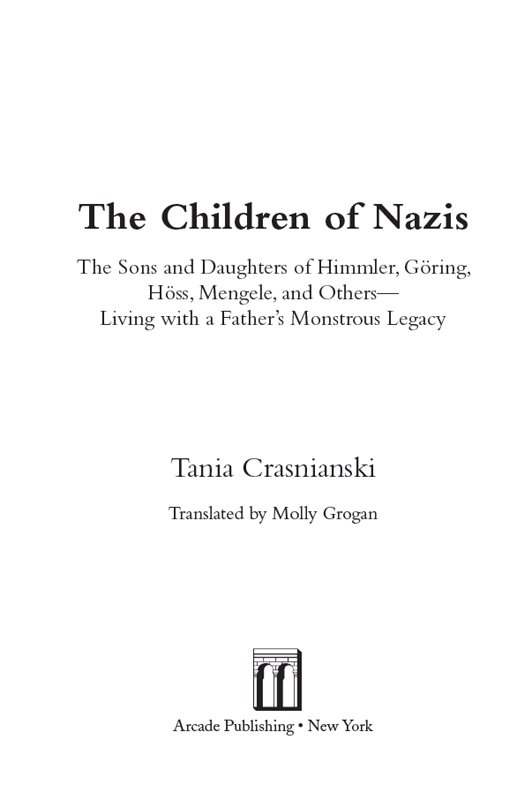

Title: The children of Nazis : the sons and daughter of Himmler, Gring, Hss, Mengele, and others : living with a fathers monstrous legacy / by Tania Crasnianski ; translated from the French by Molly Grogan.

Other titles: Enfants de Nazis. French | Sons and daughter of Himmler, Gring, Hss, Mengele, and others | Living with a fathers monstrous legacy

Description: New York : Arcade Publishing, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017035834 (print) | LCCN 2017036773 (ebook) | ISBN

9781628728088 (ebook) | ISBN 9781628728057 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Children of Nazis--Biography. | Nazis--Family relationships. | Nazis--Germany--Biography.

Classification: LCC DD243 (ebook) | LCC DD243 .C37 2016 (print) | DDC

943.086092/2--dc23

Cover design by Brian Peterson

Printed in the United States of America

For the children

For Satya, Aliocha, Ilya, and Arthur

C ONTENTS

P REFACE

This book presents the portraits of eight children and is the result of extensive research into the different existing archives, legal documents, letters, books, articles, and interviews touching on the personal lives of Nazi leaders and their descendants. None of these portraits is anonymous. Other books have preserved the anonymity of these individuals; I have chosen to name them, so that the weight of these legacies might be fully appreciated. It is also true that some of these sons and daughters feel it is easier to be the child of certain of these men rather than others.

My initial intention was to meet every one of my subjects. In the end, I interviewed only one: Niklas Frank. Some of these descendants are no longer alive; others would have had nothing to add to the content of earlier interviews. Then there are those who are no longer willing to revisit the past and still others, such as Gudrun Himmler and Edda Gring, who have almost always refused to speak of their fathers.

So that the reader might get an immediate sense of what these lives were like, each portrait opens with a significant episode, freely imagined.

R EGARDING TRANSLATIONS

In the original French edition, translations from German were made into French by the author, and corrected by the translator Olivier Mannoni. In this edition, all content is translated from French, except in the case of English-language sources, which have been quoted in the original.

I NTRODUCTION

Gudrun, Edda, Martin, Niklas, and the rest

These children have a secret. They are the sons and daughters of Gring, Hess, Frank, Bormann, Hss, Speer, and Mengele: the criminals who orchestrated the darkest period of contemporary history.

Yet their story is not recorded in the history books.

Their fathers committed the greatest evil possible and then surrendered their humanity without the slightest hesitation when they pleaded not guilty to the charges brought against them at Nuremberg. Will history remember that these men were fathers as well? After the war, a collective movement was aimed at placing responsibility for Nazi Germanys crimes and extermination policies solely on the Third Reichs principal leaders and absolving lesser dignitaries and Nazis, who hid behind a convenient formula: All that was Hitler.

Who are these individuals whose lives are discussed in this book? They share a common heritage: the extermination of millions of innocent people by their fathers. Their names will forever live in infamy.

Must anyone feel responsible, or even guilty, for the crimes of his parents? Family life leaves an indelible mark on every child. An inheritance as sinister as theirs cannot come without consequences. Like father, like son, we say. A father has two lives: his and his sons. What became of the offspring of Nazi leaders? How did they live with such macabre facts?

When one unrepentant Nazi was questioned along these lines by his granddaughter, an Israeli Jew, he gave her this answer: The guilty one is the one who feels guilty! Without

It is very difficult for children to judge their parents. We lack distance and objectivity when we look at the people who brought us into the world and raised us. The stronger the emotional ties, the more complicated such a judgment becomes. When a familys history is so disturbing, what choices does it have while living with its knowledge? Embracing it? Rejecting it outright? The responses of these children are diametrically opposed at times. Some have adopted their fathers positions. Few are neutral. Some have strongly denounced their fathers actions, yet continue to feel love and affection for them. Still others refuse to love a monster, so they deny their fathers involvement, in order to preserve the unconditional love of a child for a parent. Finally, there are those who have moved into hatred and total rejection. They carry this past from day to day like a ball and chain; it is impossible to ignore. Some have denied nothing, some have turned to religion, some have even had themselves sterilized so they can never transmit the evil to their children, and some believed they could eliminate their bad genes by masturbating! Whether they have chosen to deny, suppress, or support their fathers, or feel guilty themselves, all of them have taken a positionconsciously or unconsciouslyon the past.

Most of these children live or lived in Germany. Some converted to Catholicism or Judaism, and some were even ordained as priests or rabbis. Is this a strategy to keep

Dan Bar-On, a professor of psychology at Ben-Gurion University, interprets this type of conversion as a strategy: If you Is this an attempt to escape, rather than face, the past? The children who converted offer divergent responses, yet a spiritual calling has allowed some of them to put the past behind them.

In postwar Germanys self-imposed silence as the country began to rebuild, the Nazis descendants had to struggle to put themselves back together.

My own grandfather was a career air force man who retired to a secluded hunting lodge in the Black Forest. Although I was very close to him, he never spoke about his time in the armed forces. He is not unusual; the wars shadow hung over Germany and France for many long years, and still does, although tongues have loosened. When I was a child, we accepted this diktat of silence. Like my grandfather, the postwar generations avoided the subject. Some people finally adhered to the reigning mutism and never spoke of the war again, for fear of tarnishing the image they held of their parents. Would they have really wanted to know who their parents were during the war and the role they played in Germanys most sinister period? Nothing is less certain. The transmission of knowledge never took place. To flee the past, my German mother chose, at the age of twenty, to live by herself in France. She always wanted to be French and could not understand my decision to write this book. Why this subject? Why keep talking about it? These are questions we dont often ask.