SWALLOW THE OCEAN

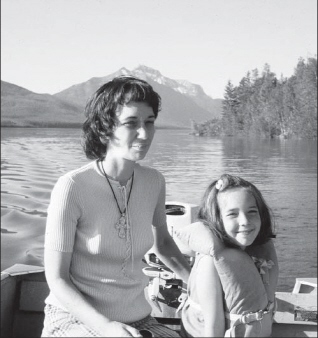

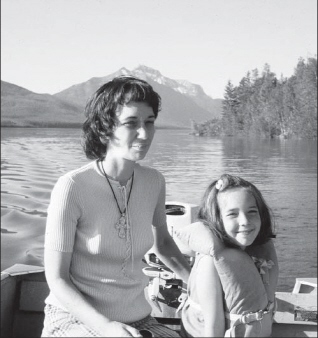

Sally and Laura in 1972

Swallow

the Ocean

A MEMOIR

Laura M. Flynn

COUNTERPOINT BERKELEY

Copyright 2008 by Laura M. Flynn

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the Publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

AUTHORS NOTE: This story is drawn from memories of real events that took place over thirty years ago. Most names, except for those of my immediate family, have been changed. In telling this story I have tried to be truthful, and where possible to verify my recollections against those of others. Nevertheless, memory is not only imperfect, it is a gifted editor, constantly compressing and expanding images of the past into something far more shapely than life as it was lived.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Flynn, Laura M., 1966

Swallow the ocean : a memoir / Laura M. Flynn.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-58243-461-2

ISBN-10: 1-58243-461-1

1. Flynn, Laura M., 1966 2. Children of parents with mental disabilities CaliforniaSan FranciscoBiography. 3. Mentally ill parentsCaliforniaSan FranciscoBiography. I. Title.

RC464.F69A3 2007

616.890092dc22

[B]

2007033247

Cover design by Nicole Caputo

Interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

COUNTERPOINT 2117 Fourth Street Suite D Berkeley, CA 94710

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my sisters, Sara and Amy

For my father, Russell Flynn

And for my mother, Sally Ann Flynn

For why do our thoughts turn to some gesture

of a hand, the fall of a sleeve, some corner of a

room on a particular anonymous afternoon,

even when we are asleep, even when we are

so old that our thoughts have abandoned

other business? What are all these fragments

for, if not to be knit up finally?

Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping

SWALLOW THE OCEAN

Content

WHEN I WAS NINE my mother explained the world to me.

Theres a battle, she said, between good and evil. And some of usthe stronghave a special role to play.

I was home alone with hermy father had moved out a year earlier and my two sisters were both at school. I was not really sickno fever, no throwing up, no stuffed-up nose, just a vague bodily unease that convinced my mother to keep me home from school. We sat together on a clear spot on the floor in the front hall, looking at the faces on the dollar bills and coins in front of us. The mess that had been steadily overtaking every surface in the apartment since my father left stretched before us in all directions. Mail had accumulated near the front door, first on the shelves of the console table, but now it extended in unstable piles along the wall halfway to the living room, which was in turn a confusion of color and texture. Layers of clothing, papers, and toys blanketed the floor. Books pulled off the shelves but not put back circled the bookshelves. Recordssome exposed, some in their white slips, some still in the album coversfanned out in a widening arc at the foot of the stereo. Near the couches, fat metal knitting needles, holding twenty or so uneven lines of scarf, were jammed into balls of yarnprojects my older sister Sara and I had abandoned.

Everyone who has ever lived is still with us, my mother said, pushing her glasses higher up on her nose. A piece of Scotch tape held them together at the corner. The faces of these men on the coins and bills in front of us, circulating among us, had an impact on people and events, for better and for worse, she explained. She was in touch with some of them, the good ones.

Like Abraham Lincoln? I ventured.

No, she said. Hes good, but not strong enough.

I was a little put out on Lincolns behalf. He seemed like the best of the lot to me. Hed freed the slaves and his little boy had died, which made me feel protective.

Whos good and strong? I asked.

She paused a moment, then said, George Washington. She handed me a dollar bill.

He looked a little mean to me, Washington, and his white curls, odd. But I could see what she was getting athe had that firm set to his lips.

She picked a silver dollar up off the floor and handed it to me. John Kennedy is the most powerful.

Certainly, Kennedy was a powerful presence in our lives. You couldnt wade through the living room without tripping over a book with his face on the cover. Whenever we were close to Golden Gate Park, my mother would drive up and down the boulevard that was named for him. Sometimes she made a special trip just to drive the full length of it, from the panhandle all the way out to Ocean Beach. She found a special gold-plated JFK commemorative half-dollar in the gift shop of the mint when she dragged me there for a tour. The coin was carved out so only Kennedys square-jawed profile hung inside a gold ring. She wore it now on a slim gold chain, replacing the heavy gold cross that had lain at the point of her clavicle for as long as I could remember.

Hes my special partner, she said.

I didnt like the sound of special partner. Not at all. There was something wrong about it.

He helps me, she continued. I didnt want to hear any more. And yet.

Helps you what? I asked.

He helps me fight the devils, she said.

I blinked, but kept going. How?

She rubbed a half-dollar between her fingers, searching for words, to describe what she knew I couldnt see.

I stretch them out in my mind, she said. She held her fingers together, then drew them slowly apart, the way you might stretch taffy or bubble gum. I stretch them until theyre destroyed.

I watched her fingers slowly come apart and could see how the devils would besolid at first like pieces of unchewed bubble gum, becoming elastic as they stretched, then turning to long filaments that finally broke and disintegrated as you pulled them apart.

I had a special place in my head for the things my mother told me. I knew a thing could be real and not real at the same time. I was a big readerI took in what she told me like a book or a story, undiluted, caught up in the moment of the telling. I wanted details. I wanted to understand how it all worked. Whether what she told me was real or not almost didnt matter. This was all treacherously real to her, and she took any sign of skepticism as betrayal. I lived in her world, and even if none of this was real to other people, the consequences were real for me.

She talked on and on. The weather, earthquakes, Vietnam, Patty Hearst, Squeaky Fromme, the signs of the times. Everything counted; everything was in play. A monumental shift was under way, right now as she spoke, and she was at the heart of it.

There is no one else, she said. I have a role no one can fill. Her pale blue eyes fixed on me from behind the thick glasses, waiting for a reply.

I nodded my assent. Her eyes slipped away. I felt relief. She gazed down the hall, past me, towards the front windows in the living room, her own head nodding up and down intently.

Sitting there on the floor next to her, asking questions, my body, eyes, and voice must have reflected the same simple faith in her that Id always felt, but a part of me was already backing away, edging towards the front door, slowly, the way you move away from a dangerous animal so it wont startle.

PICK A NUMBER between one and ten, my mother said, squeezing her wide-set blue eyes shut. She wasnt wearing glasses. She rarely did back thenvanity, I suppose. I stopped on the path, closed my eyes, and waited for the number to whisper itself in my ear.

Next page