ALSO BY GILLIAN GILL

For Rose

WHO LIVES ON IN MY DREAMS

and For All My Grandchildren

cat may look at a king .

OLD ENGLISH PROVERB

Contents

PART ONE

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

PART TWO

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

WINDSOR CASTLE,

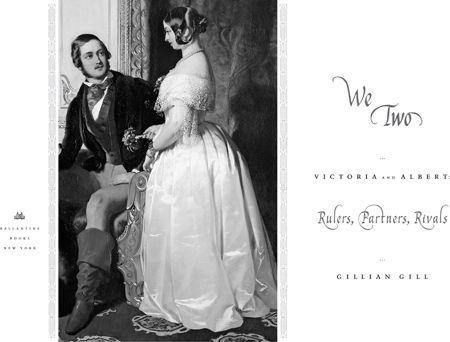

OCTOBER 10, 1839

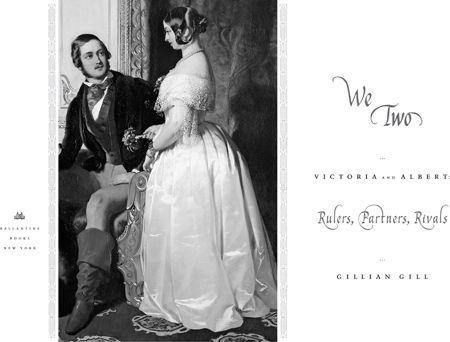

LL AFTERNOON QUEEN VICTORIA HAD BEEN EXPECTING THE ARRIVAL of her cousin Albert, and she was getting edgier by the minute. Louis XIV had never had to wait, yet here she was, monarch to an empire that put the Sun Kings France to shame, cooling her heels until some third-rank German princes arrived and she could go in for dinner. As all the courts of Europe knew, Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, dutifully chaperoned by his elder brother, Ernest, was coming to Windsor so that the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland could look him over and decide if she wanted to marry him. How dare that young man be late?

LL AFTERNOON QUEEN VICTORIA HAD BEEN EXPECTING THE ARRIVAL of her cousin Albert, and she was getting edgier by the minute. Louis XIV had never had to wait, yet here she was, monarch to an empire that put the Sun Kings France to shame, cooling her heels until some third-rank German princes arrived and she could go in for dinner. As all the courts of Europe knew, Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, dutifully chaperoned by his elder brother, Ernest, was coming to Windsor so that the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland could look him over and decide if she wanted to marry him. How dare that young man be late?

Victoria had in fact been waiting for her Coburg cousins for more than a week, and she was no longer accustomed to interference with her schedule. People nowadays waited for her, and she for her part made a point of being punctual. It was true that her initial invitation to the Coburg cousins had been less than gracious, and then, at the last minute, she had written asking them not to come until after the September meeting of her Privy Council. This request was a shade peremptory, perhaps, but more than reasonable, given the weight of her ceremonial and constitutional duties. However, the cousins had taken it badly. Albert replied in a huff that he and his brother could not see their way to leaving Coburg before October 3. Thereupon the princes crept north through Germany, lingered at the court of their uncle King Leopold in Brussels, and dallied again at the Belgian coast, waiting in vain for a calm day to embark. Victoria knew that for her male Coburg relatives, Calais and Dover might just as well be called Scylla and Charybdis, but she had little sympathy with their dread of the sea. She herself was hardly ever sick.

On finally receiving word from Uncle Leopold that Albert and Ernest were taking the overnight packet boat from Ostend, Victoria at once dispatched equerries to meet the princes at the Tower of London and bring them to Windsor posthaste. Such considerate arrangements made their lateness all the more unaccountable. It was now after seven in the evening. The Coburg party still had not been spotted heading up to Windsor Castle, and the Queen was hungry.

Victoria was trying to lose weight. At 125 pounds, she was heavy for a tiny, small-boned young woman, and she was not feeling her best. Over a stressful summer, her complexion had lost its glow and an ugly sty broke out on her eye. Her dressers were kept busy letting out the new gowns sent over from Paris by Victorias elegant French aunt, Queen Louise of the Belgians. The royal doctors were recommending that Her Majesty limit lunch to a light broth, while Prime Minister Lord Melbourne urged the Queen to take more exercise.

Such advice made the Queen testy with maids and ministers alike. Always ready to get out for a good, brisk canter on one of her beloved horses, Victoria hated to walk. Pebbles kept getting into her shoes, she complained. As for food, her appetite reminded old men at court of her uncle King George IV, a legendary trencherman of vast girth. The Queen could put away three plates of soup before tucking into her regular menu of fish, fowl, and meat dishes, vegetables, fruits, pies, cakes, jellies, nuts, and ices. In 1836 when the Duc de Nemours, the tall, dainty second son of the French king Louis Philippe, came to Windsor with an eye to marrying the then Princess Victoria, he was shocked at the way she lit into her lamb chops. Nemours made a rapid exit, and Victoria did not regret him.

NEMOURS WAS ONLY ONE of the royal gentlemen who had recently come to England to woo its queen. At twenty, Victoria had seen a great many suitors. Given her druthers, she would probably have married one of the many young English aristocrats who danced attendance on her at court. Some, like Lord Elphinstone and Lord Alfred Paget, were handsome; many could trace their ancestry back to the Norman Conquest; some were so rich they could have bought the duchy of Coburg out of pocket change. But unfortunately, not one of these delightful young Englishmen was eligible. English political tradition had long decreed that no monarch could marry a subject.

At twenty, Victoria was almost on the shelf, and conscious of it. Most princesses of her time were married off as soon as they reached puberty. She herself had been officially entered in the royal marriage market at the age of fifteen when her confirmation was celebrated. If her maternal and paternal relations had not been at daggers drawn over the choice of a bridegroom for her, she might well have been married in her midteens, while still merely the heir presumptive to the English throne.

William IV, Victorias paternal uncle, who succeeded his brother George IV to the throne in 1830, was elderly, obese, and afflicted with gout, asthma, and congestive heart failure. He knew he had not long to live and was anxious to see his niece and heir safely married to a man of his choice. The King was determined that man would not be a Coburg. He distrusted the ambitions of the Coburg family, which, in the German social hierarchy, was far inferior to his own Guelph-Brunswick-Hanover line. In Leopold, the king of Belgium, the most redoubtable of the Coburgs, William saw only the jumped-up ruler of a silly, fake nation. As for his Coburg sister-in-law the Duchess of Kent, Victorias mother, William IV positively loathed her.

William IVs preferred candidate for Victorias husband was her first cousin George Cumberland, the son of the Kings brother the Duke of Cumberland. This youth would have been a popular as well as royal choice: One English newspaper was already touting the marriage when the prospective bride and groom were nine years old. The Duke of Cumberland was heir presumptive to the Guelph familys hereditary German domain of Hanover, just as Victoria was heir presumptive to the kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Married, Victoria Kent and her cousin George Cumberland could, in the fullness of time, reunite the kingdoms. But George Cumberland, though handsome and engaging, was born with sight in only one eye, and when he was fourteen, an accident with a swinging curtain pull destroyed his good eye. Given the risk of hereditary blindness, as well as the difficulties of public life for a blind man, George Cumberland was ruled out as a suitor for Victoria Kent.

Next page

cat may look at a king .

cat may look at a king .

LL AFTERNOON QUEEN VICTORIA HAD BEEN EXPECTING THE ARRIVAL of her cousin Albert, and she was getting edgier by the minute. Louis XIV had never had to wait, yet here she was, monarch to an empire that put the Sun Kings France to shame, cooling her heels until some third-rank German princes arrived and she could go in for dinner. As all the courts of Europe knew, Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, dutifully chaperoned by his elder brother, Ernest, was coming to Windsor so that the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland could look him over and decide if she wanted to marry him. How dare that young man be late?

LL AFTERNOON QUEEN VICTORIA HAD BEEN EXPECTING THE ARRIVAL of her cousin Albert, and she was getting edgier by the minute. Louis XIV had never had to wait, yet here she was, monarch to an empire that put the Sun Kings France to shame, cooling her heels until some third-rank German princes arrived and she could go in for dinner. As all the courts of Europe knew, Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, dutifully chaperoned by his elder brother, Ernest, was coming to Windsor so that the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland could look him over and decide if she wanted to marry him. How dare that young man be late?