FROM WAR TO PEACE

IN 1945 GERMANY

MALCOLM L. FLEMING

Foreword by JAMES H. MADISON

Afterword by BRADLEY D. COOK

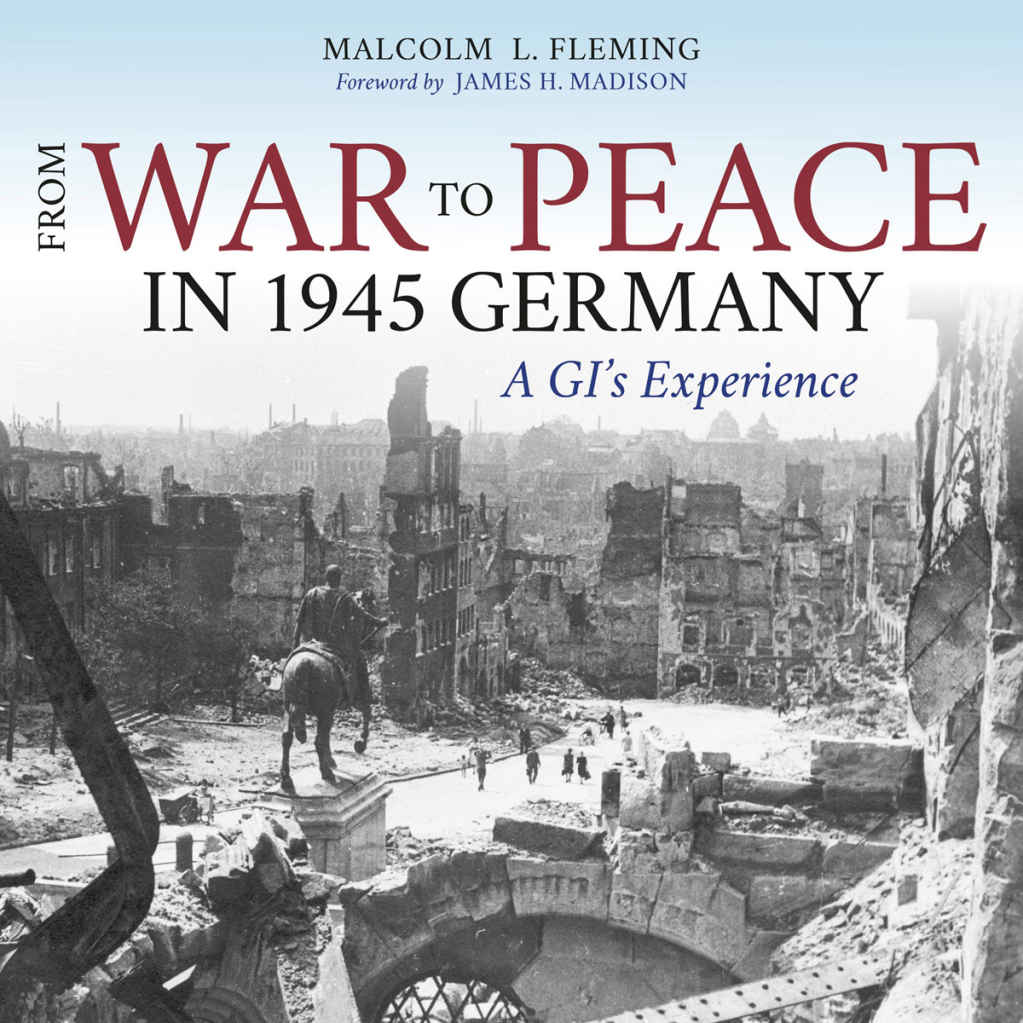

FROM WAR TO PEACE

IN 1945 GERMANY

A GIs Experience

This book is a publication of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2016 by Malcolm L. Fleming

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in Korea

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fleming, Malcolm L., author.

Title: From war to peace in 1945 Germany : a GIs experience / Malcolm L. Fleming ; foreword by James H. Madison.

Description: Bloomington : Indiana University Press, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2015023881| ISBN 9780253019561 (cloth : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9780253019615 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Fleming, Malcolm L. | World War, 1939-1945Photography. | World War, 1939-1945CampaignsGermany. | World War, 1939-1945Personal narratives, American. | United States. ArmyBiography. | War photographersUnited StatesBiography. | CinematographersUnited StatesBiography. | War photographyUnited States. | Military cinematographyUnited States. | Reconstruction (1939-1951)Germany. | GermanySocial conditions1945-1955.

Classification: LCC D810.P4 F54 2016 | DDC 940.53/140943dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015023881

1 2 3 4 5 21 20 19 18 17 16

I would like to dedicate this book to all veterans of World War II, most of whose stories are left untold but are no less worthy .

Wings over Paris.

CONTENTS

by James H. Madison

by Bradley D. Cook

Smoke generator.

FOREWORD

JAMES H. MADISON

The US Army in World War II had a reputation for SNAFUssituation normal, all fouled up (many GIs, of course, used a different f word). In Malcolm Flemings case the army made a smart choice when it took this supply clerk who had worked with a camera as a kid and trained him to be a combat photographer. Off he went to Europe with his Eymo camera to make moving pictures and a small Vollenda for still images. The result is this magnificent photo diary composed of Mac Flemings selection of images he made and kept, along with his field notes.

Photography changed our view of war. Matthew Bradys Civil War images introduced Americans to the battlefield. World War II cameras sent thousands of war pictures to home-front Americans, though only after censors carefully selected the best to build morale and urge sacrifice. Even through the fog of propaganda, it was possible during World War II to visualize combat in ways unimagined in earlier wars. Tens of thousands of still and motion picture images remain today as powerful shapers of our understanding of this war. In the flag raising on Iwo Jimas Mount Suribachi, the D-Day view of the German-occupied Normandy beaches, and the sailors victory kiss in Times Square, twenty-first-century Americans see a war fading in living memory.

Combat cameramen like Mac Fleming necessarily worked in dangerous situations, often near the very front of the front line. Some became casualities as they risked their lives to record the realities of battle. Their job of finding a good angle for a shot sometimes required standing up rather than ducking down. In one telling detail Fleming notes that when moving for the night into an abandoned German house he and other cameramen drew the top floor, affording the finest view but least security.

Fleming begins his report in Germany in March 1945, at the Remagen Bridge. American forces captured the bridge before the retreating Germans could destroy it, and so enabled a first crossing of the Rhine River. Over the Rhine Fleming drives his jeep (peep, he calls it) far into Germany and eventually to the Elbe River, where he records the linkup with Soviet troops in late April 1945. It is a grand celebration, with many toasts between American and Red Army troops. At the Elbe meeting place a friend takes a photo of Fleming standing with a diminutive Russian soldier, a female sniper, one of many such soldiers noted for their expert marksmanship. Soon after, the Germans surrender and the understanding grows that the Soviet allies had fought a different war and intended a different occupation of the Nazi homeland.

Like many other GIs, Fleming remains in Germany to record life at the beginning of the occupation. He points his camera at the physical and human cost of war, notably the steady stream of displaced persons, the thousands and thousands of prisoners and slave laborers the Nazis have forced from France, Poland, and Czechoslovakia, and of course the surviving Jews. On the rural roads and the grand autobahn, they walk toward home, away from a defeated and hated Germany, and away from the Soviet occupiers they know to be harsher than the Americans or the British. Poignantly, Fleming notes, Children everywhere.

Flemings interest in German civilians causes him to photograph women and children working in the fields, walking the streets and roads, clearing away the rubble of destruction. Like most Americans he tries to imagine their level of enthusiasm for the dreams of the Third Reich. Mixed emotions were mine, he laconically writes. At the place of the Gardelegen massacre, one of the wars many atrocities, Fleming sees Nazi deeds at their worst.

He observes the tangled relationships between GIs and German civilians. The American military authorities had issued reams of rules to govern both sides. GIs obeyed some, but not all, especially the prohibition on fraternizing with German women.

There is respite from war in a leave to Paris, the city of light that was spared most of the wars physical ruin. Here Fleming goes like a moth to brightness to make beautiful shots of the Eiffel Tower, of a loving couple on a park bench, of GIs enjoying French wineall antidotes to a nasty war.

And finally the journey home. Fleming joins the massive exodus of GIs, most of them bone-weary of war, most of them a bit surly. They wait and wait, even as Fleming acknowledges the massive scale of transport to European seaports and across the stormy Atlantic, brightened slightly by the hometown touch of Red Cross doughnuts and coffee. GIs like Mac are impatient to resume relationships and lives so utterly interrupted. Few can imagine yet that there just might be an American Dream waiting after the worst war in human history.