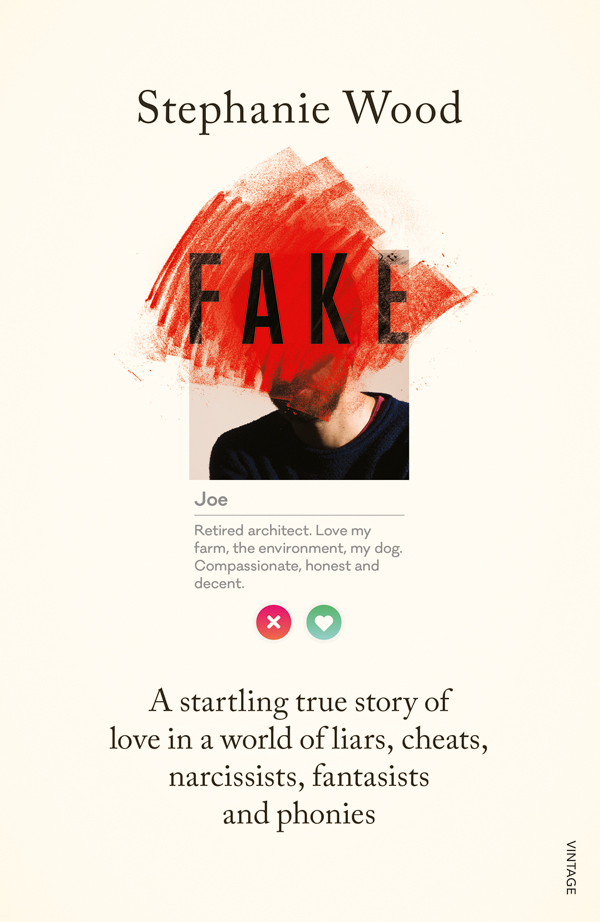

Be horrors least.

PROLOGUE

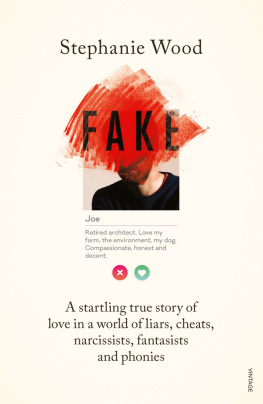

LOOKING FOR A MAN

Im on the highway a few miles out of town when the noise starts: a scraping, grinding din that jackhammers my heart into my stomach. Behind me, semi-trailers menace and the road shoulder is narrow, but I brake, pull over, and when theres a pause in the traffic, scramble from the drivers seat to investigate what Im sure must be a mechanical catastrophe. I crouch in the dust beside the front of the car and peer underneath. The damage is obvious. Some form of panel has dropped from the undercarriage and is dragging on the asphalt. The semi-trailers roar past and I decide my only option is to get back on the road and into town.

I wanted to arrive unnoticed. Im looking for a man, or traces of him, but I dont want to see him. Id even considered wearing a wig. But my cars discordant chorus is such that I might as well have hired a brass band to trumpet me into this country town on the New South Wales Southern Tablelands. In a dry paddock dotted with rusted farm equipment sheep lift their heads; a boy on a bike in the main street pauses his aimless circling to stare; a bloke in a beanie stands in the driveway of the service station and watches as I scrape and grind to a stop.

He takes a couple of steps towards me and I wind down my window. Youve got a problem there, he says. His mud-splattered truck is parked at a petrol bowser. A kelpie stands alert on the back, tied to the trucks bars. Im flustered: the last noisy miles into town have shaken me and now Im here, 100 metres from the motel Im afraid of returning to, and theres no running away from the decision Ive made to come back.

I know, I know, I say. It started on the highway scared the life out of me. I get out of the car. The wind is icy.

Ill take a look, he says. The bloke is young, well built, fetching in his roughness. A hint of flannelette shirt at the collar of his sweater. Open, unlined face and square, stubbled jaw. I cant stop looking at his hands. Powerful, leathery, the dirt running through crevices of heart, head, life and fate lines, a map of honest exertion.

Oh, would you? I thank the man and he asks me to drive over to a patch of grass at the service stations edge. There, he lies on his back and thrusts his head under the front of the car.

Nothing major, he says, showing his face again. Just a splash-guard panel can hold it up with a cable tie always carry some. He swings himself upright and goes back to his truck, rummages in tool boxes. The kelpie whirls in excitement, its lead jerks it back. The man ignores it, returns with ties and a knife, and in a minute my undercarriage is stitched up.

Good to go. I gush thanks. No worries, he says, seemingly uninterested in small talk. I try to make some, as a way of leading into a bigger question. I introduce myself, extract his name. Its Des. He has a farm in this district. Sheep. Merinos. Loves the work. Its Sunday, nearly lunch, and hes heading out to bring some sheep in.

I tell him Im a journalist and that Ive come to town to look for a man. Its a strange, awkward thing to explain, but Des seems to get it. I tell him about the man that he said he too had a sheep farm here, a few hundred acres. Said he fattened dorpers for the Chinese market on land out this way.

Dorpers, eh, Des says. Not many of them round here. I dont tell him that the man scoffed at merinos and said that dorpers a hardy South African breed that thrive on native grasses and shed their fleece were where the money was. Des doesnt need to know the details: that I once believed that when the man wasnt in the city making love to me, or raising his two children and protecting them from his crazy ex-wife, he was here. Regenerating his land with native grasses, bringing eroded waterways back to life, building fences, slashing sifton bush, shepherding his dorpers; and then, at night, filthy and bone-tired, drifting off to sleep in a rough shack with a fire blazing and his kelpie at his feet. Dreams in his head of me and the house he had designed, which he would soon build on his land beside the rubble of a 100-year-old stone cottage near a crumbling headstone standing sentry over the diminishing bones of some colonial tragedy.

Nah, dont know him. Des studies the photograph I show him, registers the name I mention. Sorry. Havent seen him round here.

Id hate to be misunderstood: Im looking for a man but without the least romantic intent. Its long over. These days, more than a year since we parted, I think of him as a specimen. Today Im on a field trip to study his habitat. But Im jittery; I do not want an encounter with this creature. Once, in his smiling eyes I saw good and gentle things. I held him tight and hoped for so much. Now I know that the smile was a simulation, the eyes black holes. I know to keep my distance.

My undercarriage restored, I drive out of town. I want to find the land and the shack. If I can find them, I will get closer to the truth. The property was the first thing the man told me about the day we met, his foundational story: the land was his purpose, the shack a cocoon in the aftermath of a bruising divorce, his work here an alibi for his absences. In emails, he wrote of this place as he might a lover, my rival for his affection: I am off to my part of the country the itch of not being there is getting to me. He described in evocative detail the challenges and joys of his farm: the heavy rain that had brought trees down on fencing he would now be kept busy replacing, the lush grass that had given his stock the runs in a biblical-tide-like catastrophe, how he would need to bring them in for drenching. Oh, the joy of that, as more than a thousand of the shitty things push up against me in the race. On the afternoons he left Sydney to drive to the farm, he would text me photographs his Land Rover Defenders bonnet cresting a hill, a golden sunset dropping into the earth. Nearly home.

By the time the man brought me to see the land and shack, months into our time together, I had surrendered and did not think I would ever need to find my own way again. In the cab of his Defender ute, his red kelpie squirmed at my feet and I let my head rest back, soaked up sharp-blue sky, gum-tree blur, white cockatoos rising, sweet magpie song. Such dreamy content: this man beside me, this country, these paddocks, that little creek, that box gum with the undulations in its trunk like the plump rolls of a babys belly. I felt I was folding into him, folding into the landscape. But I wasnt paying attention to the road.