Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Id like to thank my brothers: Aaron, who is as obsessive a Prince fan as I am, and Josh, who is as obsessive a writer as I am. Aaron is the one who, as an undergraduate at Amherst a million years ago, mined the origins of Camille for the connection-to-Herculine-Barbin theory. Josh, from suburban Miami in the eighties through to present-day Brooklyn, has put up with me and Aaron talking about Prince and then e-mailing Prince-related links back and forth, clotting his in-box. My parents deserve credit for not locking us all in a van in the middle of the forest and driving a second car home.

My children, Daniel and Jake, got exposed to Prince early, but for the purposes of infecting rather than inoculating. It took. Daniel, fifteen during the creation of this book, helped to compile the discography.

My wife, Gail, was not natively a Prince person; she went more for the Beatles and Johnny Cash. Over the course of this project, she came to admire or at least to pretend to admire him.

Friends are always central in any book-writing process, if only for the purposes of keeping an author sane. Id like to thank Nicki Pombier and Lauren Mechling, Harold Oster and Rhett Miller, Steve Weinstein and Cal Morgan and Nicole Spector and Dave Jaffe. They all contributed in different ways, sometimes by talking to me directly about the material, sometimes by distracting me from it, sometimes by providing inspiration on the writing front, sometimes just by existing. Id also like to thank Richard Nichols, who is no longer here on this planet, but is certainly on some planet somewhere (and maybe more than one), for his tireless commitment to endless conversations about nearly everything.

This book itself could not have come into the world without my agent, Nicole Tourtelot, and my editor, Gillian Blake. Thanks to both of them for focused intelligence and intelligent focus.

Special thanks to Prince and U.

To Gail, Daniel, and Jake

Forgive me if this goes astray.

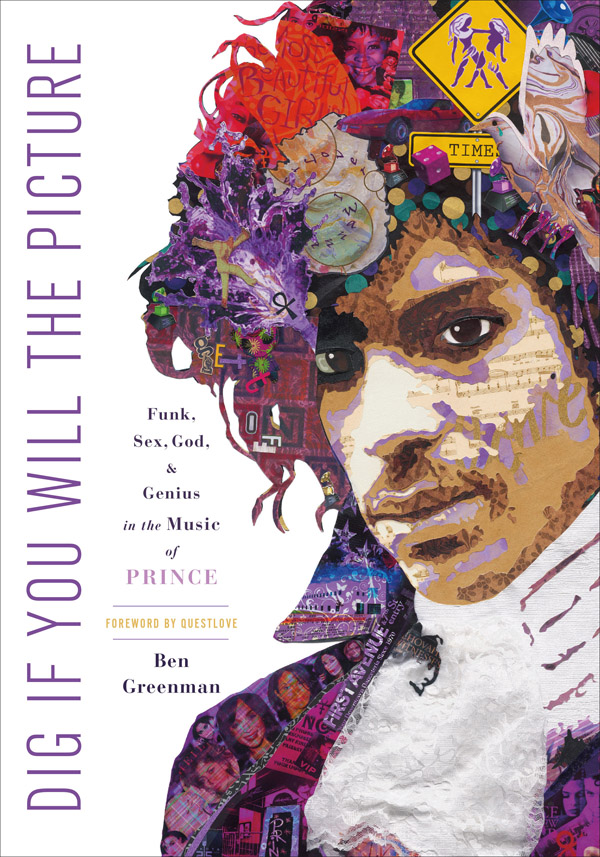

When I first got 1999 , it was 1982, and I was eleven, newly in charge of my own record-buying habits. I couldnt resist the cover, with Princes name floating on a purple field of stars. Plus, there were so many hidden meanings in the illustration: Was that a football or a smile? And how phallic was that 1, anyway? My parents were born-again Christians at that point, and Prince was a bridge too far. For starters, when you turned the album cover upside down, the 999 became 666, the mark of the beast. They didnt need more than starters.

I bought the record and hid it, but my mom found the record and threw it away. When winter came, I shoveled snow until I had enough money to buy it a second time. That one went into the garbage, too. There was a third record that just vanished without a trace and a fourth that got broken over my fathers knee. I got smarter, meaning sneakier: I found a friend to make me cassettes of Princes albums. At home, I loosened the heads of my drums and hid the contraband in them. I listened to the tapes when I was practicing, playing something totally different on the drums so that my parents wouldnt know what I was actually hearing.

Prince was in my ears and he was in my head. Starting then, I patterned everything in my life after him. I studied his fashion; I studied his affect. I studied his taste in women. He began to mentor me in musical matters, too: when Prince mentioned someone in an interview, I became voracious in my pursuit of their music. I wouldnt have started listening to Joni Mitchell without him. She led me to Jaco Pastorius, who led me to Wayne Shorter, who led me to Miles Davis. I had a simple rule: if Prince listened to it, I listened to it.

Before Purple Rain , I kept my Prince obsession close to the vest. But the day after the video for When Doves Cry premiered, I was shocked to see that my secret was out. Everyone suddenly knew what I knew, which was that Prince was everything.

* * *

Prince was singular in his music. He was his own genre. That same singularity extended to everything: he went the other way in life, too. As he got older, the way he managed his career showed off that contrary streak. It came to the forefront in the way he mastered his records, in the way he handled reissues, in the way he used (or didnt use) the Internet and online streaming services. Control was job one to him, which allowed for amazing things in the studio and onstage, unprecedented leaps of inspiration and synthesis and an energy so prolific it seemed like it would never be shut off. But it also created mistrust when it came to letting the outside world in.

I dont know. Theres so much we all dont know about Princes life, and how he lived it, and why it ended, and what that will end up meaning for us all. This book will help, not to solve the mysteries necessarily, but to frame them, to give them life beyond Princes life. This book will help to show us how much we need to know, and how much we can never know. This is what I do know: much of my motivation for waking up at 5:00 a.m. to workand sometimes going to bed at 5:00 a.m. after workcame from him. Whenever it seemed like too steep a climb, I reminded myself that Prince did it, so I had to also. It was the only way to achieve that level of greatness (which was, of course, impossible, but thats aspirational thinking for ya). For the last twenty years, whenever I was up at five in the morning, I knew that Prince was up, too, somewhere. When Prince went away, 5:00 a.m. felt different. It wasnt a shared experience anymore. It was just a lonely hour, a cold time before the sun came up.

The phrase is stuck in my head. Its the great Greg Tate weighing in on Miles Daviss passing. Talking about it, Tate wrote, seems more sillyass than sad. I think thats what Tate wrote. I went looking for my copy of Flyboy in the Buttermilk , Tates 1992 essay collection, and I cant find it. Ive looked everywhere. Still, I have the sentence in my mind, and its not coming out. Its a good way of explaining how the departures of some people from the world make it seem like the world is disappearing rather than those people. It throws the whole question of existence into flux: If theyre not here, how can we be sure that we are?

On the morning of April 21, 2016, I was at a sandwich shop, unwrapping lunch. First, I got an e-mail from my brother. Subject: Prince. Body of message: Noooo! The next message was a link from my mother, who was passing along news from KTLA in Los Angeles that authorities had been dispatched to Paisley Park to remove the body of an unidentified decedent. The dots connected themselves.

I was stunned into something more than silence: I was stunned into clamor. All at once, I heard Princes music, not snatches of a few songs in medley but all of them, brutally overlaid. I heard the volcanic guitar from When Doves Cry. I heard the scraping percussion from Kiss. I heard the keening synthesizers of songs like Automatic and the rubbed-raw passion of The Beautiful Ones. It was impossible to endure the music in that form, everything coming in at one time. It was a violence being done to some of the things that I loved the most.