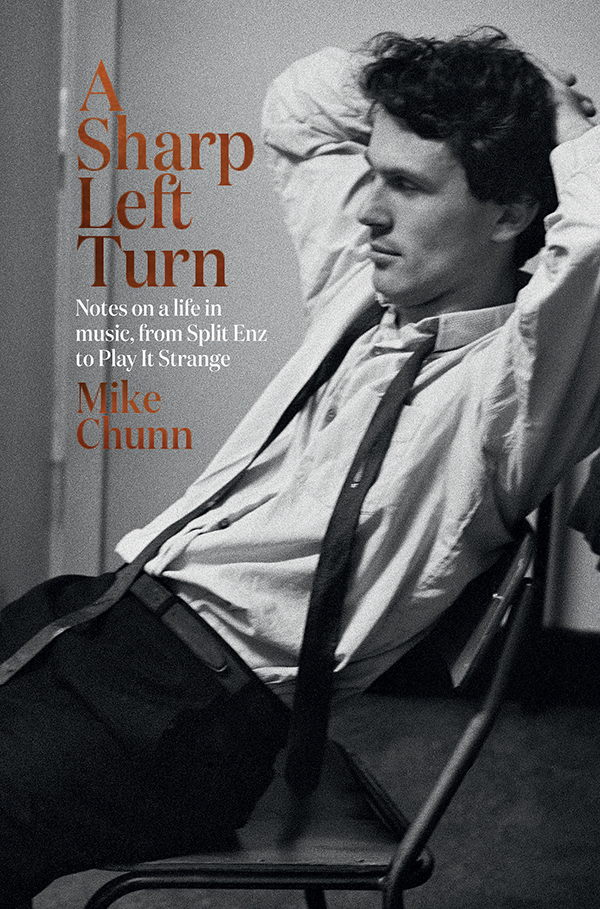

Mike Chunn is a music legend who has been involved at almost every level of the New Zealand music industry for decades. Along with Tim Finn and Phil Judd, he was a founding member of Split Enz, playing the bass on their first three albums. While he loved the stage, life on the road was a different story: unbeknown to his bandmates, he suffered frequent panic attacks and debilitating anxiety, triggered every time he left Auckland. After five years he reluctantly left the band.

In 1977, Mike co-founded Citizen Band with his brother Geoffrey, but left that band after three years for the same reason. It wasnt until 1981 that he discovered the name of his illness: the phobic disorder agoraphobia.

Mike went on to become general manager of Mushroom Records NZ, signing up artists DD Smash and Dance Exponents; later he was general manager at Sony Music Publishing NZ. From 1991 to 2003, he was the Director of NZ Operations for APRA, where he was instrumental in setting up New Zealand Music Monthan integral factor in Kiwi music gaining airtime on commercial radio.

In 2004, Mike co-founded Play It Strange, a highly respected and successful charitable trust that supports young New Zealanders in their songwriting ambitions. He is currently CEO of this trust.

Mike was awarded the Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to music and mens mental health in 2013. He is also an observer trustee of the Sir John Kirwan Foundation. He lives in Auckland.

In the late 1950s, Auckland, New Zealand, was a sprawl of skinny roads, scrawny trees and short-back-and-sides. The pace was sober and days rolled by. At the time, as the 60s loomed, New Zealand was in cultural isolation, still decades short of having some quantifiable presence on the global map. There was a World War II hangover and an increasingly anachronistic reliance on the United Kingdom to sustain and provide. This was ironic considering Britains frugal attitude at the time. Englands slow recovery post-war was in sharp contrast to the boom in the United States, where Elvis Presley, Marlon Brando and Jack Kerouac had merged from their divergent sources to forge an entertainment revolution, riding on the back of a massive commodity boom.

Through huffing and puffing, the British Empire had staved off the inevitable economic realities of the twentieth century and was yet to implode; in New Zealand, we all stood for the national anthem before movies (not God Defend New Zealand, but God Save The Queen!), the radio was full of royalty reports and shopping specials, and there was no television. We marched to a textbook beat and no one seemed to go off on a tangent. The cinemas churned through British war movies in rapid succession, with John Mills on the bridge and moustaches on every lip.

For a boy with grazed knees and grey socks, the fantasy of battle was relived through stacks of war comics and guns made from firewood and suburban driftwood. Pieces of timber surfaced out of nowhere to become Bren guns, Sten guns and Lugers. I would attack the enemy in the undergrowth, under cover of the twenty fruit trees that dotted our half-acre backyard in the suburb of Otahuhu.

In moments of stealth and surprise I would pour red-hot bullets into the chest of my younger brother, Geoffrey. He was shorter than me but not by much, and would eventually tower over me. In more ways than one. He always had a busy mind; his original songs offered to the world many years later were testament to that. Geoffreys focus when playing war games was survival. He tossed his skinny legs in the air and ran from the bullets. I shot him. He would refuse to die. I, on the other hand, threw myself onto the rotting fruit and muddy earth, all cadaver and carcass. Occasionally I would play alone and shoot myself. Then my mother would call me in and I would fade, exhausted, over a hot meal.

The branches of time in the Chunn family tree reached back to the late nineteenth century, when my grandfather Alfred was born in Greymouth. His father had emigrated from Wiltshire in England. Alfred was a mischief and a vagabond so it was no surprise when, in the collision of time and responsibility of which he took no notice, he became a bookie. He was called Bunny, as he was always running from the police. A bookie is a wanted man unless he knows which cops to buy beer for. Fortunately, Bunny did. He always had a pile of pound notes in his back pocket, like fallen leaves of gold that he had cleverly picked from punters pockets.

My grandmother was an Irishwoman called Babs, born and raised in Cork. She was born Mary but no one seems to know why she became known as Babs. Or how she got to Greymouth. She was Babs Chunn and that was that, and she was a barmaid. In time she became an alcoholic as she tried to cope with the tawdry behaviour of Bunny, who painted an invisible dotted line through the middle of their house. He lived in one half, and Babs and their two sons, Jerry and Jack, lived in the other. Bunny would appear in the evenings to eat dinner with them, say nothing, then go back across the dotted line. Gone. My father, Jerry, remembers his mother sitting in a chair weeping.

And then the war came. Bunnys slippery, clever nature ensured that his sons didnt go to Europe to fight. With his pocket full of money, he funded Jerry to attend Otago Medical School. Doctors were needed at home in a war, and that included med students. Farmers were also needed, to make sure that cows and sheep were plentiful. Meat in wartime is gold. So Bunny bought a farm and got Jack to run it.

Babs died in the late 60s. The kind, lush lawns of their house on Chunns Hill in Greymouth faded before her eyes. And, as much as she thought she might be going somewhere in life, the truth was a stationary wall of dead hours. Hopefully she would sit in the late-afternoon sun and watch the shadows of the boundary trees stretch and orchestrate the slow, methodical arrival of dusk.

Bunny staggered on, in the Kingseat psychiatric hospital in South Auckland. He died in 1976 after battling a mental disorder that no one seems to have a name for. He used to come to our Otahuhu home one Sunday a month in a striped three-piece suit and give each grandchild a half-crown. Maybe he was still taking bets on horses in Kingseat. He must have known his horses well.

My mother, YvonneVon for shortwas also born in Greymouth, the daughter of Owen and Francie Williams. Her father was a peripatetic principal of primary schools, so it was by chance that Greymouth was Vons birthplace. She remembers nothing of it, as the Williams family moved on shortly afterwards. Small towns rolled off their car bonnet with the sea breezes. They always seemed to be close to the ocean as they drifted far and wide around New Zealand. Tokomaru Bay. Waitara. A few others lost in time.

The Williamses marriage was also lost in time. It was failing, so Von was sent to boarding schools, where she forged a sense of place, a camaraderie with like minds.

At the end of the 1940s, after her parents divorced, Vons mother, Francie, married Sam Turner. He was different, old Sam. He had a large wooden Spitfire propeller on his study wall. When I was a kid I used to wonder what had happened to him in the war over there in England. Did he ever fly into a turbulent sky peppered with German bombers? His thumb on the trigger. His heart in his mouth.

Sam didnt want to talk about it. He was more of the present. He was on the board of companies like UEB and Craigs foodstuffs and things like that. He would hand out tins of baked beans. He had lines to stockbrokers and seemed to have a lot of shares. Whatever that was all about.

Vons father married Nell, a shopkeeper, and they lived in Katikati till the end of their lives. Brother Geoffrey and I would go there on the bus and stay a week or two. Their street never had any traffic driving down it. There was a sense of the stationary and the nameless. Did anyone wander? Did they ever take a different route to the dairy? How would one ever know?

Next page