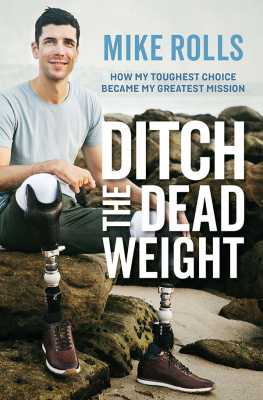

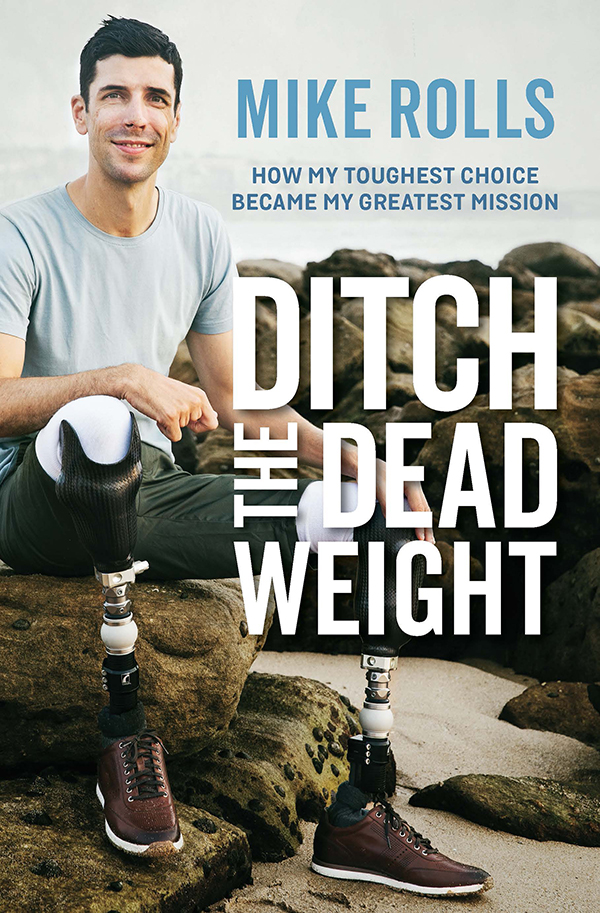

Published in 2018 by Murdoch Books, an imprint of Allen & Unwin

Copyright Mike Rolls 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Murdoch Books Australia

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest NSW 2065

Phone: +61 (0)2 8425 0100

murdochbooks.com.au

info@murdochbooks.com.au

Murdoch Books UK

Ormond House, 2627 Boswell Street, London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: +44 (0) 20 8785 5995

murdochbooks.co.uk

info@murdochbooks.co.uk

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 76052 394 7 Australia

ISBN 978 1 76063 499 5 UK

eISBN 978 1 76063 639 5

Text design by Fleur Anson

Cover photography by Jeremy Simons

CONTENTS

I lay in bed, taut with excitement, checking my clock every few minutes. Id hardly slept. I was eighteen years old and heading off on my first end-of-season footy trip to Tasmania. Quarter to six that would do. I reckoned that was a time I could legitimately wake up Mum without getting shouted at. I grabbed my bag and trotted down the hallway.

Come on, Kaff! It made me laugh to call Mum Kate, Kathleen, Kaffy or whatever sprang to mind. I stuck my head around my parents bedroom door and could see Mum was doing her best to ignore her annoying teenage son. But I was undeterred there was no way I was going to be late. See you in the car, Kathleen!

I threw my bag in the back of the car and, to encourage my driver to move a little faster, gave the horn a few quick blasts. Mum appeared a few minutes later, struggling into her coat and looking halfway between irritation and amusement.

We werent even out of the driveway before she started the last-minute pep-talk. I expect you to behave like an adult, MikeYour dad and I have trusted you To be honest, I wasnt really listening in my head I was one step closer to the team adventure.

Bye, Ma, I called over the bonnet of the car as I rushed to join the boys. I heard a quiet Hmmm? from behind me. Mum was standing by the drivers door, pointing to her cheek. Seriously? A kiss goodbye, in front of my footy mates? I was mortified, but I knew there was no ignoring her this was a family tradition. I slunk back and planted the worlds fastest kiss on her cheek, then a lightning quick hug and I was off.

Its one of the last things I remember before the shit hit the fan.

The walls were yellow, stained, with holes in them, as if to let the plaster breathe. Occasionally I opened my eyes but, when I did, the light was painful. My hands were tied to the rails of a hospital bed, but I couldnt have sat up, even if Id wanted to. Balloons floated above me, some with writing.

Later, when I drifted into consciousness I would clutch and pull at the tubes sticking out of my body and then my hands would be restrained again. I had no voice. I tried to speak, to ask questions but, even when I mustered all my energy to shout, no noise came out. When I held my hand up close to my face I could see two fingers had gone. The rest of my body was covered by a sheet so I couldnt yet see that my fingers were not the only thing Id lost.

The pain wasnt intense or in any particular place, but the pain I did feel was everywhere. It was hard to decipher exactly what was hurting. I twisted slightly to the left and felt stabbing pain. I moved the other way to find relief but it never came. The tubes were everywhere. The constant beeps and blips of the monitors became a soundtrack to my bewilderment and escalating fear. My neck ached. I didnt know anything other than that something was very, very wrong. I faded back into oblivion.

My memories of Hobart Intensive Care are vague and hallucinatory. The doctors had performed a tracheotomy and inserted a breathing tube into my throat, so I couldnt speak to ask what was happening. I drifted in and out of consciousness, the morphine causing wild visions and nightmares.

When I came to, a woman Id never seen before was telling me Id been very sick. Considering my pain and the surroundings, Id worked that part out for myself. Her words were a blur but I could make out something about a disease. It was impossible to concentrate and yet I desperately wanted to understand what she was saying. I tried to talk but I was still voiceless. Finally, the woman told me it was important for me to rest and then she left.

I was smelling fresh air for the first time in what seemed like forever. It was glorious but the sun hurt my eyes. I didnt know where I was going, but I was relieved to sense I was leaving the hospital. Someone was holding my hand with both her hands my sister, Sarah. She was smiling at me and telling me something. I could feel her love and I was overjoyed to see her face; I squeezed her hands so tightly she almost winced.

I was being moved from Hobart ICU to the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne by air ambulance. My family had rushed to Hobart as soon as they heard I was ill and had rarely left my side, but I hadnt been aware of them in the room. All my energy had been diverted to survival and clinging onto life. That moment of looking at Sarah as we prepared to leave Hobart felt like the first time Id really seen her, even though shed been at my bedside for weeks.

The first time I registered Mums face, she looked broken completely shattered. She tried to smile at me, wanting to reassure me and hide the fear we both felt. I started to sob but there was no sound, just tears streaming down my face. She held my hand and we cried together. Dad had a look on his face that I didnt even recognise: fear, pain, helplessness, confusion all rolled into one. He didnt say anything but hugged me while I sobbed silently.

As I gained a little strength after several weeks in the Alfred, I became increasingly frustrated at not being able to speak. I had so many questions and almost no answers. I later learned that the doctors didnt want me to find out everything at once and were drip-feeding me little bits of bad news at a time. They were worried that the shock of the full extent of my injuries might impair my recovery, which was already painfully slow.

Because I couldnt communicate with my voice, Mum made an alphabet chart out of a manila folder. I could point to each letter to spell out a word or question. It was a slow, laborious process, but at least I could ask questions and find out what had happened to me. What I learned was devastating.