Contents

INTRODUCTION

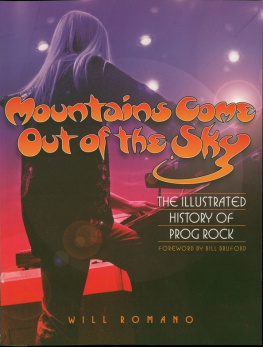

More Songs About Wizards and Hobbits

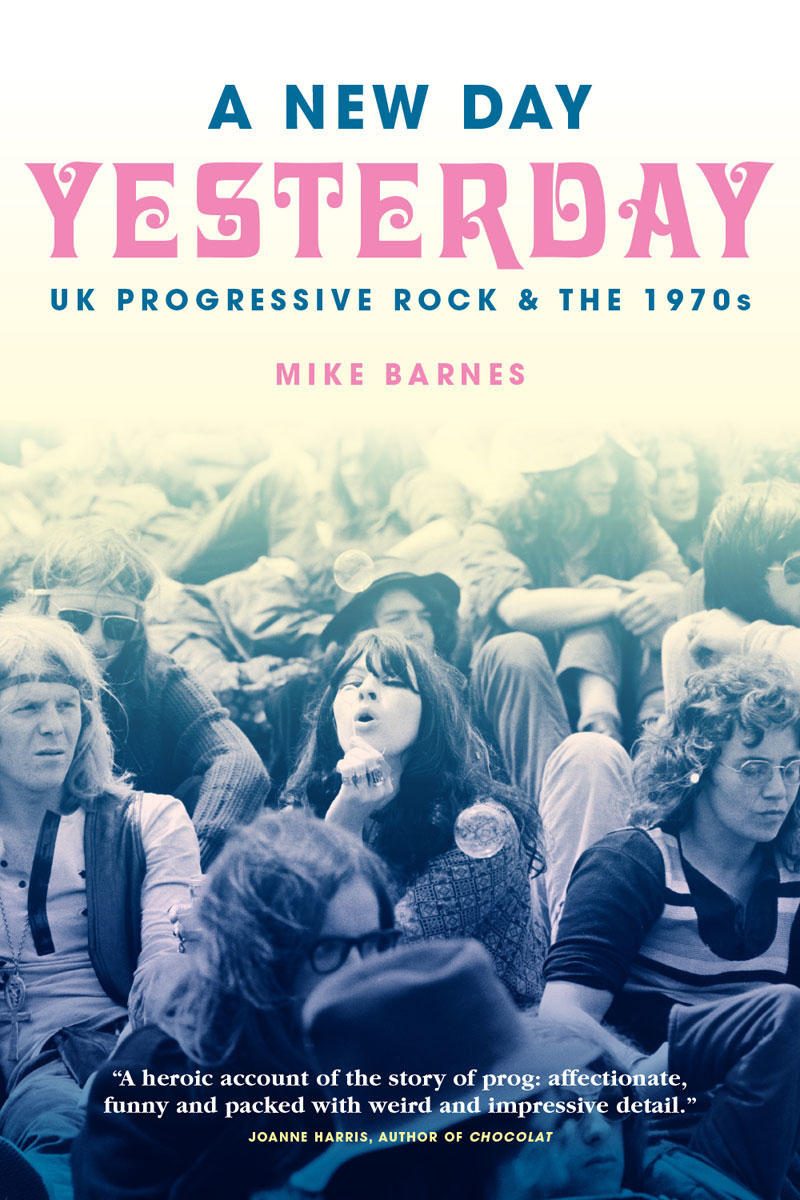

Progressive rock isnt that about wizards? asked a considerably younger friend via email when I told her that I was thinking of writing this book. Well, yes and no, I replied, and then changed the subject, amused but also rather embarrassed by her perception of my literary intention.

Afterwards I had a bit of a think: there was a band called Silly Wizard, but they were more folk rock; The Wizard Of The Keys was a minor character in Gongs Radio Gnome trilogy; Uriah Heep released an album Demons And Wizards in 1972, but although they had some aspects in common with the progressive rockers, they also had another stack-heeled boot in the hard rock camp; Rick Wakeman was known in Seventies parlance as a keyboard wizard, and had posed for promotional photographs for his 1975 concept album The Myths And Legends Of King Arthur And The Knights Of The Round Table wearing a conical wizards hat but best stop there.

The heyday of progressive rock is long enough ago now for received wisdom to suggest that it was all about wizards, elves and hobbits, and so it should be retrofitted thus and consigned en masse to the dustbin of history. But in fact almost none of it had anything to do with this fantastical roll call. So, what are we actually talking about here? What is, or was, progressive rock?

Labelling music into genres may be a journalistic construct, but there is usually a rough consensus. Free jazz, jazz rock, Britpop, soul, blues, funk, grunge, hardcore, rave, folk and ambient all conjure up an aural image of their typical sounds. If we are talking about Merseybeat, then we know we are dealing with beat music that was initially played in the Liverpool area in the early to mid-Sixties.

But progressive rock defies easy categorisation. Its a term that, according to the majority of the musicians I have spoken to, was rarely used to describe the music as it was made in the Seventies, but has since become a way of labelling a wide-ranging genre, while its modern shorthand, prog, can be used pejoratively. Imagine saying it while pulling a face.

But one has to start somewhere, and for the purposes of this book, progressive rock was essentially ushered in by the burst of creativity in the psychedelic era, from 196668 although era seems a bit of a grand title for a shift in creative thinking whose first phase lasted only a couple of years. But such are the ways that we attempt to make sense of changes within an artistic continuum.

The first major wave of progressive rock swelled up in 1969, reached its peak in the mid-Seventies and then began to dissipate into different tributaries towards the end of the decade. But the Seventies was a particularly open, fertile and mutable time musically, with so many different influences and styles feeding into what was played, that borders and definitions remain contestable.

After psychedelia had thrown open the doors of perception, the challenge was to impose order on its lengthy, expressive freakouts and the chaos that these could potentially lead to and to experiment with form, structure and dynamics: the imperative was to make new musical shapes. With progressive rock anything was creatively possible and, stylistically, everything was up for grabs, and so the groups mixed up elements of rocknroll, R&B, psychedelia, classical, the avant-garde, folk, jazz, free improvisation, non-Western influences and more soul than is generally acknowledged even attempts at multi-media into brand-new musical hybrids. Lyrics encompassed social satire, invented worlds, sci-fi, ideas from literature, stream of consciousness word paintings, a hippieish striving for enlightenment, a few love songs and even a smattering of politics.

As always with these musical shifts, there was no clear beginning. The earliest example this writer has seen of progressive in print, as an adjective to describe rock music, was with reference to the psychedelic group, Tomorrow, in early 1968, while in that year the Small Faces were referred to by Keith Altham in the New Musical Express as progressive pop. Jimi Hendrix was also labelled progressive in some quarters, an accolade he certainly deserved. The p word was used to describe Caravan in the sleeve notes of their self-titled debut album in October 1968. But it was in use even before then.

Melody Maker journalist Chris Welch claims he was the first writer to coin the phrase progressive rock when writing about Cream in 1967, in a nod back to progressive jazz, the way pianist Stan Kenton described his music of the late Forties. Writing in International Times in 1970, Mark Williams described Caravan, Soft Machine, Mighty Baby and Family as British ethnic rock music an interesting idea, but the label never stuck.

In the late Sixties, rocknroll music was still alive and well, with many of its pioneers still playing, but it was beginning to show its age. In this new, post-psychedelic artistic climate, rocknroll was suddenly expanded by a mass of new ideas, creating a different kind of rock music. Calling it progressive was as good a nomenclature as any. Music is constantly progressing anyway, but in the early Seventies, developments in rock music happened at an unusual speed, with musicians eager to stride into the new creative space that was opening before them.

Suddenly, basic 4/4 twelve-bar rocknroll seemed anachronistic, like something from the distant past, as rock was now open-ended and could potentially go anywhere and everywhere. Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull has this to say on progressive rocks questing spirit: When I was asked to define what makes a progressive rock musician, I said, well its a person who just gets bored easily. People who think, Well, I can do that, but whats next?

What was initially envisaged as a sustainable, imaginative alternative to mainstream pop, with one foot still in the counterculture, could, on paper, have been a minority interest, but eventually became in the case of some groups commercially huge in the heyday of the album. Major labels caught on and invested substantial amounts of money in this new thing, and there was enough of a market to allow a number of independent labels to spring up. And with a record-buying public looking for new kicks, it also infiltrated the charts, with hit singles in the early Seventies by Jethro Tull and Family in particular, who made appearances on the BBC TV singles charts showcase, Top Of The Pops.

Other reactions from friends to the news of this book project ranged from raised eyebrows of interest to lip-curling sneers of disdain. Such divided reactions are nothing new. Progressive rock was both revered and reviled in its heyday from 1969-74. And theres the rub. One musician I talked to, a practising punk of a certain age, admitted that although hed like to read the book, he couldnt stand the music and that obviously Yes were shit. I was concerned, although not entirely surprised, that to some, this music was simply synonymous with naff or less polite descriptors.

Although this easy way of dismissing nearly a decades worth of music bothered me, I could see why it had arisen. At its height, progressive rock was powerful and potent enough to attract millions of fervent true believers, but when it began to lose its way in the mid to late Seventies a view shared by many of the musicians I have spoken to it did what no other form of 20th-century popular music had managed to do. It provoked a backlash of epic proportions: the emergence of UK punk rock in 1976.