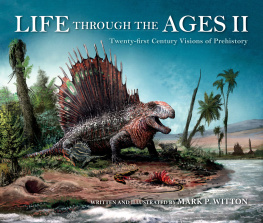

LIFE THROUGH THE AGES II

Life of the Past

James O. Farlow, editor

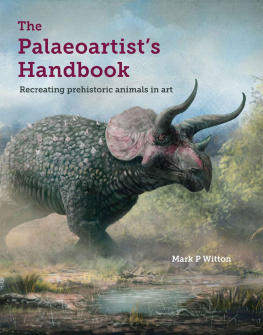

LIFE THROUGH THE AGES II

Twenty-first Century Visions of Prehistory

WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED BY

MARK P. WITTON

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2020 by Mark Paul Witton

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Manufactured in Canada

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-04811-0 (hdbk.)

ISBN 978-0-253-04814-1 (web PDF)

1 2 3 4 5 25 24 23 22 21 20

Contents

Acknowledgments

ALL OF US INVOLVED IN SCIENCE STAND ON THE SHOULDERS OF the generations of researchers who came before us, and books such as this one represent the summation of work from hundreds, maybe thousands, of individuals. Collective thanks are owed to these folks who help us uncover the history of life and our planet, as well as those who workoften in trying circumstancesto understand and rectify our current biodiversity crisis. Its hard to write a book about the evolution of life without feeling more invested in the state of life on Earth and the future of this planet. I hope reading this book will help others feel the same way I have as Ive written it.

Some specific individuals must be acknowledged for their contributions to this book and their encouragement about its content. This work has benefited from input by Victoria Arbour, Nathan Barling, James Boyle, Markus Bhler, Richard Butler, Vicky Coules, Gary Dunham, Jim Farlow, Mike Habib, Luke Hauser, David Hone, Christian Kammerer, Julian Kiely, Darren Naish, the research staff at National Museums Scotland, Felipe Pinheiro, Steve Sweetman, Mike Taylor, and Mathew Wedel. There are possibly others whom I have forgotten to mention: if youre among the omitted, feel free to demand that I buy you a beverage of your choosing next time we meet.

My ability to write educational books and create art is supported by a number of patrons who supply me with a monthly salary at Patreon. com. You guys have made, and continue to make, a huge contribution to my life, for which Im sincerely thankful. I hope this book justifies your very kind support of my work.

My parents, Paul and Carol Witton, need a mention for their continued patience with a son whom they see increasingly rarely, owing to my being ever busier with different projects that bleed into vacation time and weekends. (I promise Im not just putting you on speaker phone while I work through your phone calls, honest.) But please spare most thought for four-time book widow Georgia Witton-Maclean, who somehow still puts up with my long, late work hours and my continuous gibbering about whatever cool thing Ive been painting or writing about, and demands only that I watch Deep Space Nine with her in return. Shes quite OK, that wife of mine. But thats our little secretdont tell her I said that.

LIFE THROUGH THE AGES II

Introduction

In the Shadow of Knight

THE STORY OF LIFE ON EARTH IS HARDLY A NEW TOPIC FOR AUthors and illustrators. Popular books on this subject have existed since Franz Ungers 1851 Die Urwelt in ihren verschiedenen Bildungsperioden (The primitive world in its different periods of formation), a landmark work that described and illustrated (courtesy of artist Josef Juwasseg) the changing environments and inhabitants of our planet for the very first time. Countless examples of the same concept have appeared since then, created by authors and illustrators of varying backgrounds and levels of expertise. Most have largely been forgotten, but the 1946 book Life through the Ages is fondly remembered and, thanks to modern commemorative editions, it remains in print well over 70 years since its first publication. The ongoing popularity of Life through the Ages has almost certainly been helped by the fact that its author/illustrator is one of the most celebrated and influential artists of extinct animals to have ever lived: Charles Robert Knight (18741953).

Nowadays, we consider Knight a paleoartist: an individual who restores the life appearance of fossil animals and ancient environments using paleontological and geological data, supplemented by a firm understanding of modern natural history to fill in our knowledge gaps about prehistoric worlds. Although Knights career saw him capture many natural history subjects, he is probably most famous and fondly remembered for his depictions of prehistory. The discipline of paleoart is as old as paleontological science, stretching back to at least the year 1800, and we can view Knights professional life, which ran from the 1890s to the early 1950s, as bridging the nineteenth-century foundation of paleoart with a more modern, established period characterizing the mid-twentieth century. Much of the contrast between these eras reflects the rapid accumulation of paleontological knowledge that occurred in the late nineteenth century. Paleoartists working in the early 1800s often had only scrappy fossils to work from, resulting in reconstructions that, though sometimes surprisingly insightful considering the material they were based on, were not close approximations of their subject species. The discovery of superior fossils in the latter half of the 1800s allowed for new reconstructions that eclipsed the scientific merit of their predecessors. For dinosaurs, in particular, many of these discoveries were being made in the western United States by museum teams from the northeast of the country. As a young and talented natural history artist situated around New York City in the 1890s, Knight was in a prime position to capitalize on these new discoveries. By 1894, his habit of sketching animals and specimens in the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) was recognized by museum staff, and he was asked to restore the life appearance of the extinct piglike mammal Elotherium (now Entelodon). Knights career as a paleoartist was thus launched, and thereafter he spent much of his professional life recreating extinct animals in various artforms.

For two decades Knight worked closely with the director of the AMNH, Henry Fairfield Osborn, who promoted Knights work heavily. Osborn seems to have regarded Knight as a museum brand and pushed his work both to advertise the museum and to spread AMNH influence to other institutions. Knights work became such a beloved component of the museums exhibits that installations were eventually designed with his artwork in mind: it was important for fossil specimens to be associated with, but not to obscure, his murals and illustrations. Still, Osborn also saw Knight primarily as an artist, not an independent scientific intellect. He referred to Knights AMNH works as OsbornKnight restorations, and in some instances he used Knights work to visualize his idiosyncratic and infamous ideas on human evolution. Though they developed a productive and successful partnership, Knight and Osborn did not always work in harmony; the two men often disagreed on matters of artistry, science, and artistic ownership. Their working relationship came to an end in 1928, when Knight agreed to a commission from the Field Museum in Chicago. For Knight, distancing himself from Osborn was probably to his benefit, as it demonstrated that he could produce excellent paleoartworks without Osborns direction. Osborn, however, thought Knight would flounder without his support and was critical of his later work, including his iconic murals for the Field Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum. Despite their less-than-amicable professional split, Osborn and Knight remained friends until Osborn died in 1935, with Knight writing fondly of his colleague after his passing.

Next page