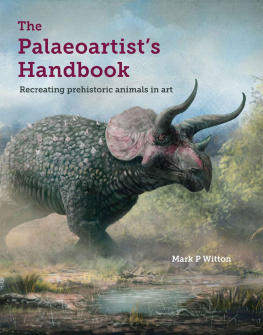

The

Palaeoartists

Handbook

Recreating prehistoric animals in art

The

Palaeoartists

Handbook

Recreating prehistoric animals in art

Mark P Witton

CROWOOD

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

Mark P. Witton 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 462 9

Fontispiece: Nemegt Sunrise. Sunrise over the Nemegt River in Cretaceous Mongolia greets a female Conchoraptor gracilis with a breakfast of hermit crab inside a Viviparus shell. (R. Amos)

For my parents, who, even now, arent persuading me to get a sensible job

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am incredibly fortunate to have many friends who are talented artists, historians, anatomists and palaeontologists, and this book would not exist as it does without our many conversations and collaborative projects. Id especially like to thank Mark Evans, Richard Forrest, Mike Habib, Dave Hone, Christian Kammerer, Chris Manias, Liz Martin-Silverstone, Darren Naish, Ilja Neuland, Elsa Panciroli, Mike Taylor, Katrina van Grouw and Matt Wedel for fuelling my brain with ideas, sometimes while numbing it with beer. Ashley Morhardt is thanked for allowing reproduction of data from her Masters thesis and commentary on the data therein.

Im thrilled to be joined in this book by some of the best palaeoartists currently working: their contributions elevate this work to a level I would be unable to attain on my own. Sincere thanks to Raven Amos, John Conway, Julius Csotonyi, Johan Egerkrans, Rebecca Groom, Scott Hartman, Bob Nicholls, and Emily Willoughby for supplying their art and thoughts to this project.

Finally, a little sentiment. My parents have always encouraged me to pursue the intellectually rewarding but professionally challenging field that is palaeontology, and its only through their encouragement that Ive gone so far along this scientific and artistic route that Ive ended up writing a book on it. Their continued support of my unusual career choice is appreciated more than British reserve allows me to convey on paper. Georgia Witton-Maclean, who received a disacknowledgement credit in my last book for being such a (admittedly worthwhile) distraction during my book writing process, graduates to the acknowledgement section for this book for being incredibly supportive while this project came together. She not only seems to find my constant rambles about palaeoart interesting but wins the Best Wife Ever award for accommodating all the books, fossils, bones, frozen carcasses and long working hours that palaeoartistic and authorial habits bring. If I can offer my first tip for being a palaeoartist before the book begins in earnest, its this: make sure you have an awesome spouse.

1An Introduction to Palaeoart

The ordinary public cannot learn much by merely gazing at skeletons set up in museums. One longs to cover their nakedness with flesh and skin, and to see them as they were when they walked this earth.

HENRY N. HUTCHINSON, 1910

M ost people are aware that palaeontologists, the scientists who study extinct life, sometimes work with artists to produce works of art featuring ancient species and landscapes. The details of this process are mostly murky in the public sphere however, being rarely discussed outside of specialist venues and of seemingly little interest compared to finished illustrations, paintings, sculptures or animations of fossil creatures. In fact, there is a whole discipline for this form of artistry, replete with its own specialist knowledge base, skill sets, recognized artists, and a long history, all dedicated to the recreation of extinct animals, plants and their landscapes in illustration and scupture. This discipline has been variably named over the last two centuries, but is best known today as palaeoart ().

Fig. 1.1 The Cretaceous dromaeosaur Microraptor gui restored eating a fish (Jinanichthys). Every detail of this painting is based on fossil data, including the plants and environment, the depicted behaviour, and even the colour of the Microraptor, making it a supreme example of the genre known as palaeoart. (E. Willoughby)

The terms palaeoart (sometimes spelt paleoart this reflects the American-English spelling paleontology instead of the English spelling palaeontology) and palaeoartist were created by celebrated palaeoartist Mark Hallett in his 1987 article The Scientific Approach of the Art of Bringing Dinosaurs Back to Life. The term is a portmanteau of palaeontological art, palaeontology being the scientific study of extinct life and fossils. Somewhat confusingly, palaeoart is also used in archaeological literature to refer to artistic creations by prehistoric people. An alternative term for art of reconstructed fossil animals, palaeontography, has been coined by another artist, John Conway, and might offer a solution to this confusion. Palaeontography is used in some circles, although palaeoart remains the dominant term by far and will be used throughout this book.

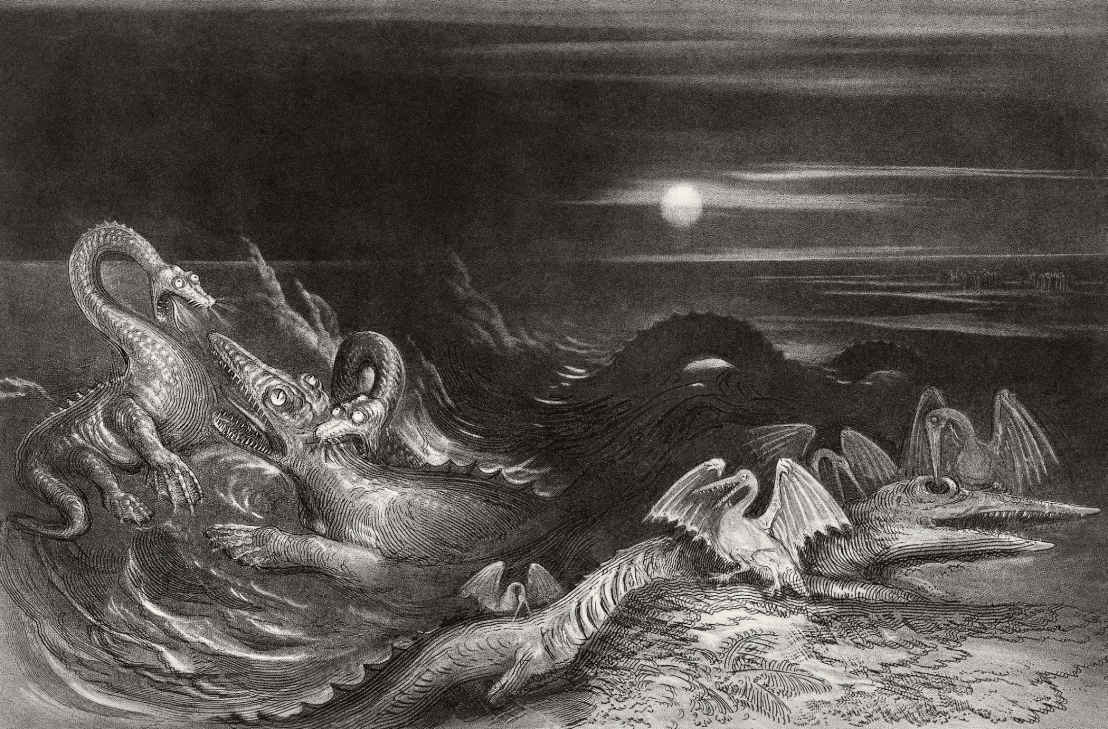

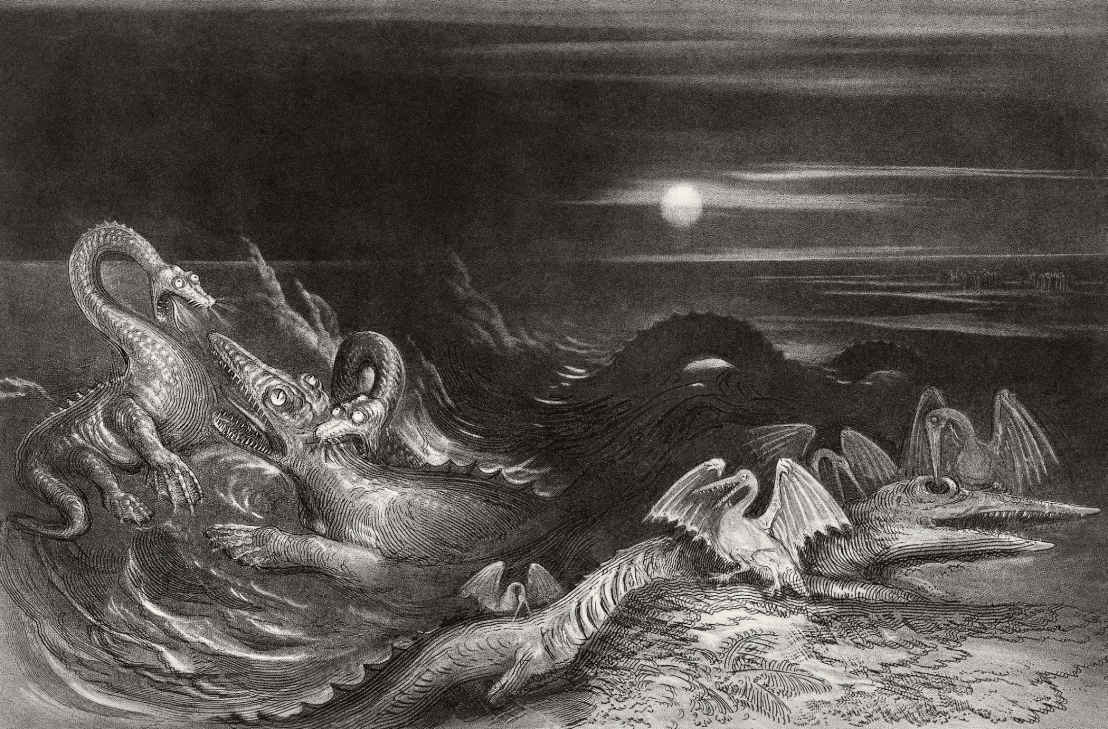

Fig. 1.2The sea dragons as they lived, a classic palaeoartwork from 1840. (R. Martin)

While the discipline of palaeoart was only recently named, its history extends as far back as palaeontological ). The first modern piece of palaeoart a sketched restoration of Pterodactylus antiquus, a Jurassic flying reptile dates to 1800 and was produced for private correspondence between scholars. In the next half century, palaeoart entered scientific literature, was then used as an educational device for students, then to educate the public, and eventually as the basis for merchandising opportunities. Initially practised by scholars themselves, natural history artists began to enter the employment of scientists to facilitate the production of grander and more technically accomplished artworks early in palaeoart history. This relationship between scientists and artists continues today. We can thus essentially see the origins of our modern palaeoart industry a tool for scientific, educational and commercial application dating back to the 1850s, over 160 years ago. In that time palaeoart has undergone several movements and reinventions, shown a steady increase in popularity, and is now recognized as one of the most important assets in the popularization of palaeontology and scientific outreach.

Next page