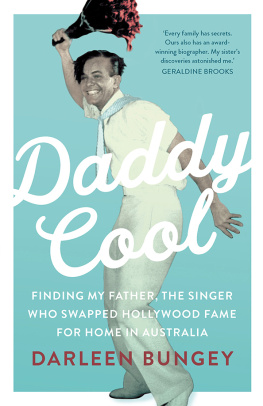

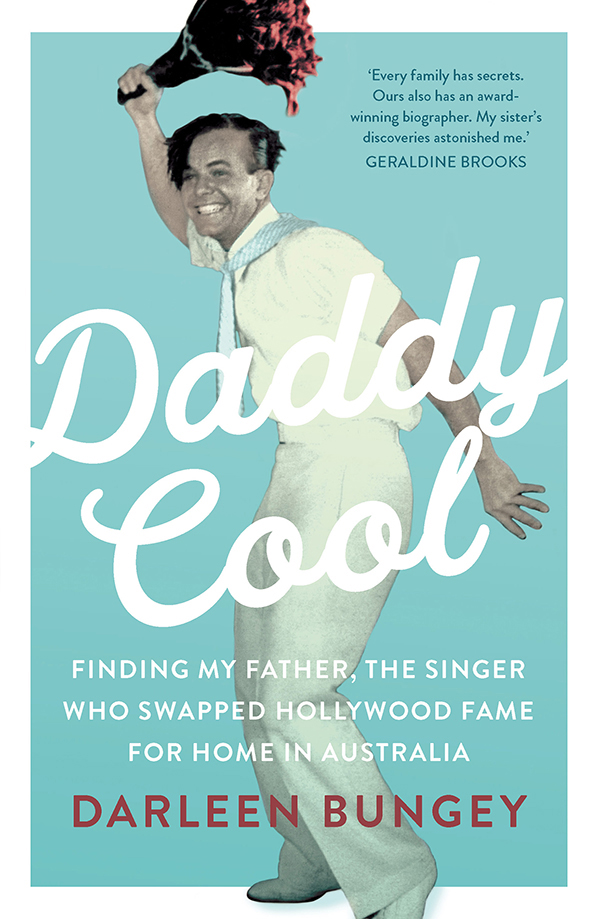

First published in 2020

Copyright Darleen Bungey 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 967 3

eISBN 978 1 76087 408 7

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

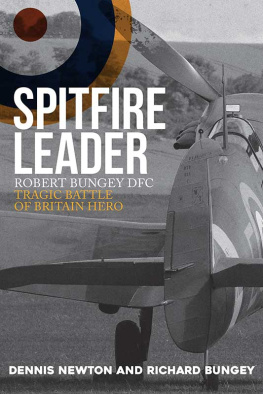

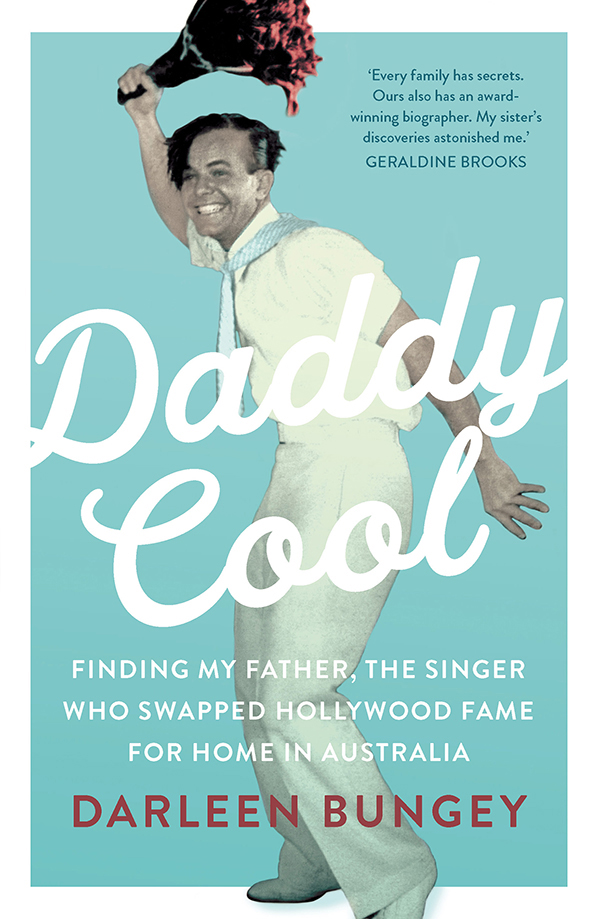

Cover design: Lisa White

Cover photo: authors collection

To Sam and Cassie

Pass it on

Who in the world am I? Ah, thats the great puzzle.

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

HIS TWO AUSTRALIAN DAUGHTERS carried him across the broad sands towards the headland that rises sharply from the last northern beach in the city of Sydney. Sun sparked off the lighthouse at the top of the scrubby rise. Giant boulders, elemental, lay at the base of the cliff on a rocky bed that spilled into the sea.

We were young enough then, in 1994, to easily negotiate the long haul over the tricky wet passage of stones leading to one of the most magnificent boulders. It would be his headstone and our farewell point to the man with several names. In his first life: Robert Ahern CutterBuster, Bob. And in his second: Lawrence BrooksLawrie.

Surrounding us were ancient rock engravings and burial sites once created by the Guringai people. Tens of thousands of years later, a Customs House had been built. In the 1800s, this area had been a bushrangers hideout, a place for smugglers of sly grog. On this day, my sister brought a bottle of whiskey, our fathers favoured spirit. It would be our toast to him.

In a beach suburb several kilometres away, his wife had no idea what was taking place. She knew no way of ever saying goodbye to the man she had loved for so long. When he had been cremated, and after the wake, our mother didntcouldntdiscuss what might happen to her husbands ashes, to the remains of the man she had loved for almost half a century. And in the years that followed, she never asked.

High above the Tasman, the sea that merges into the Pacific, we cast him adrift. We imagined the ocean would carry him from his adopted home of Australia to his birthplace on the coast of California.

In the dust were the sights and sounds of him, particularly the sounds of him. His wonderful tenors voice, a voice that could rise above all faultclear, true, piercingly tender.

The deep bass of the ocean orchestrated his leaving. In an airy tumble, he briefly smudged the blue sky above and the white wash below. And then he was on his way. Eighty-seven years were dissolving, reforming found, lost, then found again.

MY FATHER READ LIKE he sang.

Curled up in my bed, watching him turn the pages of Alice in Wonderland, his soft voice blanketed me. When he said, This is your first grown-up book, I grew like Alice, far larger than my room, swelling with pride that I had my fathers undivided attention and, at my tender age of six, that he considered me an adult.

He was a wonderful reader. Words were important to him. He treated them like notes of music. Vowels and consonants were carefully articulated, each sentence perfectly pitched. Like a concert conductor, he drew action from the verbs, colour from the adjectives and guided the punctuation with precisionswift, slow, halt, stop.

Sitting next to me, reading aloud, he must have recognised Alices plight: he knew how it felt to fall from one world into another, to change identity. Over the years, although infrequently, he would speak of that foreign past; but for the most part it lived in a deep tea chest stored indifferently on the sandy soil under the house where stone foundations supported the wooden bungalow.

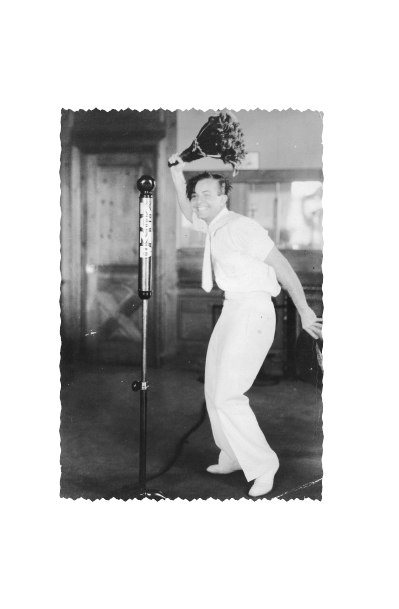

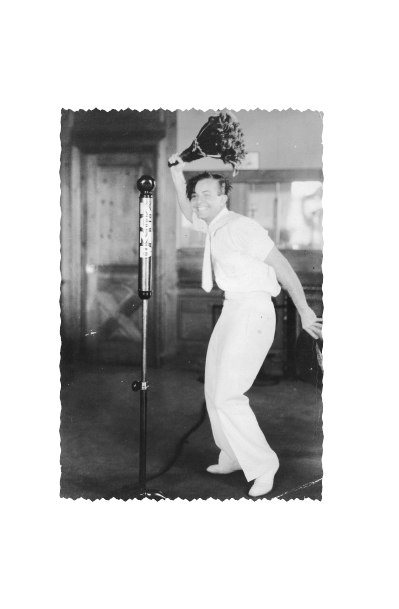

In this crate his history tumbled. His handsome young face crumpled on crushed newspapers. His 78-rpm vinyl recordings warped in the heat. Paper mites censored his reviews. His publicity photographs slowly faded. And spiders continued to spin like a metaphor over this tangle of another time.

In his late thirties, he had married for the fourth and last time. At this midpoint in his life, he had shed a life of glamour and travel for a packed lunch, for a nine-to-five job. Occasionally, the names and places from his pastthe singing venues of the 1930sthe Coconut Grove, the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, the St Francis Hotel, the Biltmore Bowlwould crop up in conversations, but a child pays meagre attention to such details. And while, in the 1950s, I wore my precious Mickey Mouse ears and looked longingly towards the USA as one big Disneyland, it held little sway with me that my father had once called it home.

Up until my mid-teens, he took singing engagements that fitted around his day job. The man who sang at the kitchen sink was the man who sang on the radio every week. The man who caught the train from a working-class suburb of Sydney to the Town Hall station was the man on his way to sing for the Queen. The man who stood in the living rooms of our neighbours homes, singing in celebration of their anniversaries and birthdays, was the man I watched rise magically from the stage floor in the majestic State Theatre to sing alongside the organist. It was a double life that to me seemed normal. It wasnt until he was pictured leaning against a piano on the front page of the newspaperthe paper that he worked for as a proofreaderthat I realised he was different to any other father I knew.

In the years after his death, I began paying close attention to the lives of others. I wrote biographies of men who, not necessarily seeking fame, didnt shun it when it arrived: one rushed towards the spotlight, while the other backed into it. Although they were painters not performers, I began to question if it wasnt my father who was at the heart of my endeavours. Was he the man I had always needed to un-riddle? Not only the man who inexplicably reversed his life, but a father who could trouble as well as delight; a man my mother would at times ask me to understand, to forgive.

Finally, I decided the tea chest was my rabbit hole. Rather than never find the answers to my mysterious father, I chose to plunge in.

IN AN EARLY PHOTOGRAPH, black-and-white and stamp sized, I am six months old. I sit in a pram looking towards my father who, shirtless and wearing an old pair of trousers, sweats in the sun as he rakes grass seeds into a small patch of soil bordering the front of a just-built, two-bedroom semi-detached red-brick bungalow in Marrickville. I am watching the man who, in that year of 1948, had just been written up in Tempo magazine as a suave, sophisticated heart throb famous for his love songs. The writer declared that, if Lawrie Brooks were to go to England, he would be a greater singer than England has ever produced.

Next page