Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Top Hat, White Tie, and Tails by Irving Berlin 1935 by the Irving Berlin Music Co, Administered by Williamson Music Co. All Rights Reserved. Used With Permission.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

wrote, were portents given of earth and ocean.

physician, his nerves worn ragged by his inability to get cool, leaped to his death from a fifth-floor apartment.

But the weather had broken. A series of rain showers swept through the city followed by a blast of cool wind from the north. By nightfall on Friday, July 26, 1935, the temperature hovered around 70 degrees. There was a slight breeze in the air.

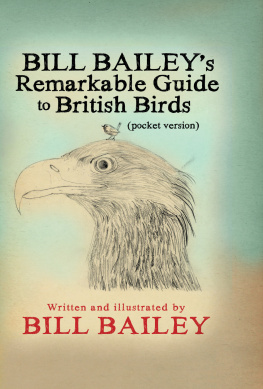

Bill Bailey, dressed uncharacteristically in a dark suit, striped tie, and Panama hat, was ready for his mission.

. This, in his heavy Jimmy Cagney brogue, was how you pronounced burnt liver.

Just twenty, Bailey had been a shoeless newsboy, grammar school dropout, juvenile delinquent, panhandler, turnstile jumper, insubordinate dockworker, stowaway, hobo, vagrant, thief, reformatory inmate, drunk, lyin son of a bitch, apprentice sailor, and connoisseur of the pleasures of the harbor. His life was transformed when he was working as a fireman (operating the oil burners to generate steam to power the ship) on a freighter traveling between New York and London. He was so outraged over the mistreatment of a stowaway of color, so nave, so trusting, so beautiful at heart, that he joined the Communist-led Marine Workers Industrial Union and, shortly thereafter, the Communist Party itself.

During the torrid days of July 1935, Bailey was mired on the beach without a ship. Broke and homeless, he was sleeping on the benches of the old International Workers Order hall on Union Square.

He had plenty of time to huddle with fellow unemployed seamen of leftist bent and discuss the civilizational assault that Adolf Hitler was conducting before the eyes of newspaper and radio correspondents who were relaying the news to the world. Over the previous few months, the Nazi state had launched its second major anti-Jewish onslaught since Hitler was elevated to power two and a half years earlier, proof that the initial-stage actions against Jews in March 1933 were just the beginning of the promised eradication of an existential foe. The Hitler government was also attracting international attention with strictures against the last vestiges of antiregime sentiment, targeting groups as varied as far-right paramilitaries of non-Nazi allegiance and professional comedians who lacked proper deference for regime leaders. The front pages blared the news about a months-long drive against the Catholic Church. Of particular note to the radicals on the waterfront, the Nazi government seized an American sailor from a US-flagged liner in Hamburg and threw him in a concentration camp for plotting to circulate antiregime printed materials.

Something had to be done, Bailey said.

Gizeh out for a stroll, declared the New Yorker.

The Bremen steamed twice a month into New York Harbor, easing with slow-moving grandeur into the Hudson River slip reserved for the Fatherlands premier vessel along what was known as luxury liner row. The area around Pier 86, which extended a thousand feet into the river from the foot of West Forty-Sixth Street, was a tiny province of the Third Reich with bars, restaurants, shops, and newsstands catering to a German-speaking clientele. Here, on the western edge of Manhattan Island, European civilization touched American soil (or cracked cobblestone) in the era before the standardization of air travel, before the transatlantic jets at LaGuardia and Kennedy.

they had an acquaintance on board or not. The topside areas with views of the shimmering cityscape resembled a packed subway train at rush hour.

that 4,800 nonpassengers had boarded the ship for the affair. With the addition of 1,300 passengers and a thousand German crew members, the population on the Bremen hovered around 7,000. The revelers included a Hollywood movie star, a delegation of Protestant clergymen, a Rockefeller heiress, the new US ambassador to Norway, a future secretary of the navy, a collection of wealthy financiers, the governor of Pennsylvania, a Honduran nobleman, a Chicago meatpacking mogul, and the two-year-old grandson of the president of the United States.

On the stretch of shoreline under the looming bow of the forward-facing ship, a few thousand anti-Nazi activists gathered to protest the mounting crisis in the Third Reich, chanting slogans, holding signs, and delivering speeches. Arise ye prisoners of starvation! they sang, using that eras translation of The Internationale. Arise ye wretched of the earth! The ranks included communists and socialists, anarchists and social democrats, high school students and old-timers, concerned citizens and cranks, gentiles and Jews, and, a rarity in those days of bedrock racism, blacks standing alongside whites.

Surrounding the demonstration was a New York Police Department (NYPD) contingent of more than three hundred officers, including a hundred undercover detectives and a few dozen ten-foot-cops on horseback. A private security firm hired by the German shipping line deployed an additional fifty uniformed men and five plainclothesmen.

Another several hundred people at least, curious onlookers out for a stroll on the pleasant summer evening, lined the waterfront to get a glimpse of the spectacle.

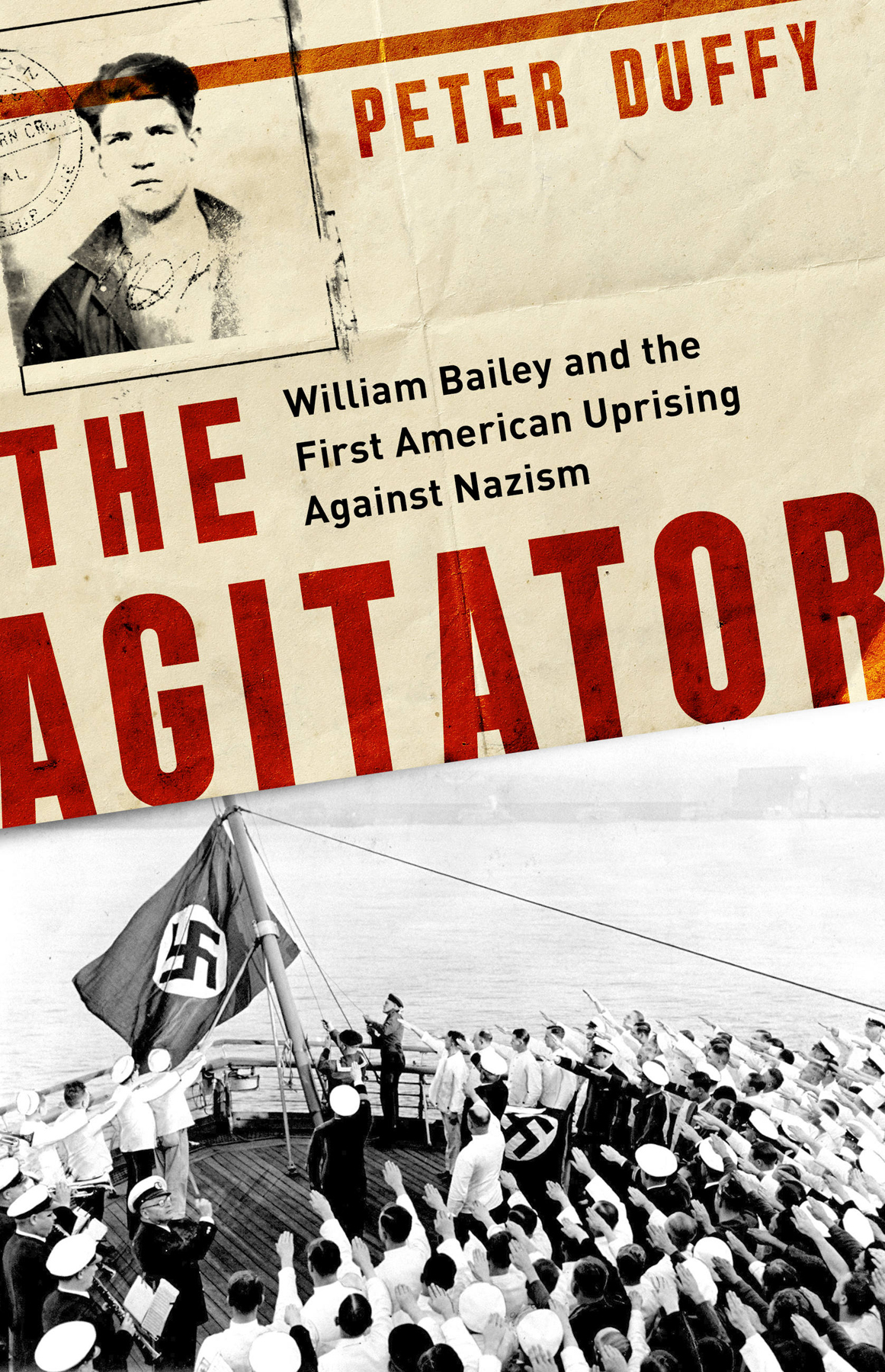

All eyes were turned toward the centerpiece of the evenings festivities, the swastika flag that waved from the short staff at the nose of the Bremen, hovering 50 feet over the stretch of unfenced shoreline where the rally was occurring. The flag was illuminated by a high-powered arc lamp beaming down from the ships bridge.

Bill Bailey was one of about a dozen itinerant seamen disguised in stylish clothing who slipped through police lines and crossed the visitors gangway onto the