Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Karla Stover

All rights reserved

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.43965.832.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934221

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.553.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

It was a time when dreams came true, the dreams of those old-timers and true believers like Carr and McCarver who looked at the bay in the forest and saw a city.

Murray Morgan

PART 1

THE LAST OF THE PIONEER YEARS

TACKLING PACIFIC AVENUE

Considerable difficulty is being experienced in the construction of the sidewalk on part of Pacific Avenue. In some places the walk is built over the edge of the roadway necessitating the construction of trestle work thirty feet high in places.

Tacoma Daily Ledger, September 27, 1883

Sometime in the 1870s, a man named Arthur Locke decided to follow the Northern Pacific surveying lines from his Spanaway Lake home to Commencement Bay because though hed heard about the bay, he hadnt seen it. Locke tracked the stakes through the forest, walked down what is now Pacific Avenue and ended up at a tent built around a tree stump where Old City Hall is. The tent was a restaurant, so he ate dinner and walked back home.

Not long after that, James Tilton, Washington Territorys first surveyor general, was asked to plat a town. For a salary of $300 a month, currency, he laid out one-hundred-foot-wide streets in the business district and forty-foot-wide residential streets. However, city fathers werent happy with Tiltons ideas for draining Tacomas clay bank hill, and his employment was short-lived. Army Corps of Engineers assistant engineer Colonel William Isaac Smith was asked to weigh in. He was in the area, working on Pacific Railroad surveys and explorations along the southern route of a proposed transcontinental railway route. Smith surveyed and re-platted. From the railroad terminal where the wheat grain elevators are to the top of the bluff at Eighth Street and Pacific Avenue, volunteers graded an eighty-foot-wide road that residents called either Picnic Road or the Magnificent Drive. It wasnt very magnificent, however. The problem was that Pacific Avenue was a dirt road, therefore either muddy or dusty. For a number of years and at regular intervals, Chinese laborers were hired to wheel in barrels of gravel and spread it on the road.

Many of the stores were perched high. Some were on a level with the sidewalks while others were below. The walks themselves were not level. The pedestrian must have a care where he stepped; night travel was precarious, and not safe without a lantern.

Herbert Hunt

By the 1880s, neither residents nor developers knew whether New Tacomas business district was growing north or south. (Old Tacoma, aka Old Town, and New Tacoma merged on January 1, 1884.) The projected construction of a grand railroad station near Ninth Street was shelved. Instead, a modest wooden depot went up at Seventeenth Street. When people arrived, they either went north to the new Northern Pacific Building or the Tacoma Hotel or south into the small commercial district with its wholesale establishments, blue-collar boardinghouses and piecework businesses. Whether north or south, though, Pacific Avenue was unsafe because of poor lighting and the state of its roads and sidewalks.

When the first streetlights were installed, they used coal oil, and Marshal E.O. Fulmer had to light them at night and douse them in the morning. The presence of streetlights was so important, though, when the city added new ones, charges of favoritism about their locations were made.

In May 1884, an ordinance allowing for the illumination of Pacific Avenue by electric lighting was postponed. Instead, the city fathers directed their attention to the inspection and regulation of chimney flues. Two years passed before Tacoma Light and Water Company was ready to launch itself into the street-lighting business. The first electric streetlights went into service on December 26, 1886, along a three-quarter-mile stretch of Pacific Avenue. What the lights did was illuminate the shoddy state of Tacomas roads. A typical news items was one like this: On Thursday night a drunken man and a Chinaman were involved in a fist fight near the Railroad House and while in the thickest of the conflict, fell from the walk into the deep mud of the adjoining gutter and were almost lost from view. They emerged from the soft slime with their ardor entirely cooled.

During circus parades, while dogs barked from rooftops, wagons regularly mired down in the streetcar rails. Skunk cabbages grew in the in the moist soil, and people crossed Pacific by jumping from one piece of driftwood to another. Comments such as, Give us anything but mud, Give us the first pavement that can be laid down and The council should have done something long before this, reached the ears of the city councilmembers. Clearly, a solution was needed, and the first remedy tried was laying planks. Property owners were assessed, and the work began.

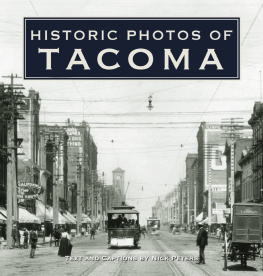

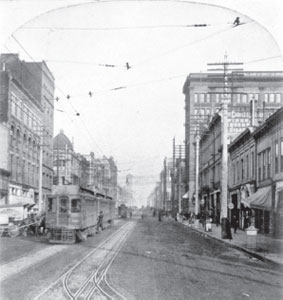

Fourth and Pacific Avenues after the Tent Period, circa 1880. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-101072 (b&w film copy neg.)].

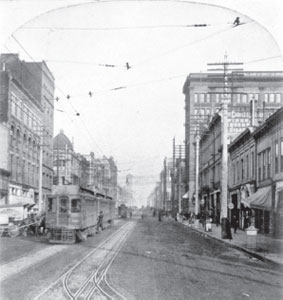

Pacific Avenue, 1904. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [LC-USZ6-174].

How extensively Pacific Avenue was covered with planks isnt known, but they ran south at least as far as the Jefferson Street intersection. The planks were one foot wide and six inches thick. Stringers were laid every three feet, and the planks were attached to them with spikes. They extended from the curb to the streetcar lines. Though an obvious improvement over dirt and mud, they had their disadvantages. J.A.Q. Sproule, owner of the Cow Butter Store at Pacific Avenue and Jefferson Street, said their biggest disadvantage was that they were so flammable. Carelessly tossed cigarette and cigar butts, sparks from streetcar rails and firecrackers meant the smart shop owner kept a bucket of water handy to douse fires. Another problem was that spaces underneath the planks became handy hog wallows for wandering pigs, and according to rumors at the time, at least one escaped felon found a place under the planks in which to hide. Another problem was that Tacomas elevation rose about 360 feet in just eight blocks downtown, and horses had a hard time getting traction on the slippery wooden inclines.

Different parts of town had plank roads for varying lengths of time. In 1892, the Tacoma Daily Ledger ran a scathing article on their state with physicians weighing in: there was no ventilation under the wood, which retained dampness and decaying impurities. Added to this, they said, the byproducts of horses, and you have a mess. City officials knew many of the roads, Pacific Avenue included, needed work, and the city attorney had to decide whether property owners could be assessed a second time.

Next page