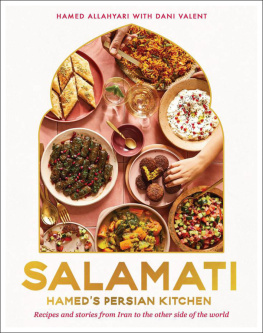

To my older brother Hussein who was my role model, inspiration and my best friend for life; to my mother who has sacrificed so much for me to be alive, well and to have a normal life; to my dad who quietly put his life on the line for all of us and has been a soundboard for every problem Ive ever had; to my younger brother who has always stood by my side no matter how bad it got.

T here was nothing special about our house in Herat, but it was all I knew as home until I was ten years old. It was built of clay, like all the other houses in our neighbourhood, and it was made up of four fairly bare rooms, with Persian rugs covering the floors. We lived with the families of two of my Dads brothers, so it was always full and busy, and my brothers and cousins and I were always causing trouble.

There was a kitchen area where Mum would make kichiri, and a sitting and dining room with no sofas or dining chairs, only patterned pillows or nalincheh. We didnt eat our meals at a table, but around the sofra, an eating area on the floor.

The Taliban had taken control of Herat before I could remember, and rules in the city were strict. Curfew was 8pm. No one went out after dark, and women werent allowed to go anywhere on their own. Even us children had to be careful who we spoke to, what we said and how we said it. The Taliban were everywhere, so it wasnt a good idea to do anything to stand out.

I was the middle of three boys, the jokey troublemaker sandwiched between my cheeky, liked-by-all older brother Hussein and my quieter, more reserved little brother Hessam, and we were sheltered from most of what went on with the Taliban. But I would sometimes overhear the elders talking about what they did stories of mercenaries decapitating civilians and quickly sealing the neck with hot wax so they could bet on which headless body would stay standing the longest.

Then, one bright, and surprisingly warm winters day when I was ten, everything changed. I had run home to fetch our football a crumpled piece of lightweight PVC wrapped in another torn plastic bag and as I went into the house I could hear Mums voice from the kitchen. She was practising a speech she was writing. Word that this speech was happening had spread around the community, but in hushed voices.

We have the same rights as men! She paused, repeated herself quietly, and then shouted it. We have the same rights as men!

This kind of talk was normal in our house, but I knew it spelt danger. Mums interest in womens rights had begun a few years ago when some of the other mothers in the neighbourhood had asked her to mentor their teenage daughters. Mum had a reputation for being an amazing cook, and she was brilliant at sewing. The neighbourhood mothers were keen for their daughters to learn the home skills they would need when they got married and, having only sons, Mum enjoyed teaching them. She treated them like daughters.

But as the girls she mentored came and went, Mum began to realise that once they got married they wouldnt be much more than servants for their new husbands. How could she prepare them for that? The Taliban rule meant that girls had few rights anyway they werent allowed to go to school and had no choice but to wear the full burka. Outside the home they were considered useless.

Mum was going to give her speech the next day, which was a Friday. The community would be coming together for Jummah, the Friday prayers, and as many people as possible would hear it. But that meant it wouldnt just be the women she was trying to help who would be listening; the Taliban would hear it too.

I watched from the living room as Mum moved around the kitchen, making the dinner and practising her speech. Then Dad came in.

Dad was Mums biggest fan. He was always getting under her feet and bustling around the kitchen, but he always supported her. He didnt look like most Afghans he was fair-skinned with hazel eyes and he had run a china shop with one of his brothers before opening the pharmacy where he now worked. Family was everything to him, and he backed Mums ambitions to fight for female equality. But he also loved us all and wanted to protect his family, and he knew Mums speech was dangerous. Opposing the Taliban publicly would put all of us in danger, and over the last few days wed noticed his nerves starting to show.

Where are the boys? he said now. The whole neighbourhood knows about your speech. I really hope you know what youre doing.

Mum looked up from the stove for a second and then turned back to what she was doing.

Theyre playing football, she said. And dont worry about tomorrow we have God on our side.

I crept out and went to find my brothers.

Our football pitch was a dusty alley in the neighbourhood where we had piled rocks up as goalposts. It was quite late when I arrived back with the ball, and the sun was already going down. I was always on the same team as my brother Hussein and played behind him, moving around the pitch so he was always in my sight. Although Hussein was four years older than me, Mum had trained me to keep a watchful eye over him, and I was always looking for any sign that he was in trouble.

Hussein had had a rare heart condition since he was born. Hed already had two operations in India: one when he was just a baby and another when he was six. But hed got worse as he got older, and despite trips to Iran and Bulgaria to get help we were told that the only place he could get proper treatment was the UK or America. We knew that one day Husseins illness would catch up with him and we would have to leave Afghanistan, but for us that seemed far in the future.

In the meantime, I had become an expert at checking up on Hussein, watching his breathing, the way he moved and the colour of his skin. I took my responsibility very seriously.

Now, as I looked down the alley, I saw Husseins eyes light up as he spotted a gap in the oppositions defence. He chased a perfectly placed through-ball. Go on, Roberto Carlos! I shouted.

But as he powered off the line and skipped past his marker, he suddenly stopped and hunched over. I panicked. I could hear Mums voice in my head repeating her instructions: Take his pulse, then get help.

There was a beat of silence, then I took a breath and ran towards him.

Bro! You okay? I said, trying to sound calm. By the time I reached him he had crouched down in the dust, his skinny shoulders rounded. He looked up at me, panting.

Yeah, Im fine.

Wed been running around, he had raced down the pitch to get the ball, maybe he was just thirsty? No. I had a bad feeling about this.

I put my fingers on the right side of Husseins neck just as Mum had shown me and began counting. One, two wait ! I couldnt keep up. It felt like machine-gun fire. My mind went blank for a moment, then I picked him up and put his right arm over my shoulder. I had seen football players carrying off their injured teammates like this. I could be a hero.

As we began stumbling home, I kept my fingers on Husseins wrist and eventually his pulse dropped to match mine. Of course, then he was quick to tell me that he could carry himself, so I let go but kept an arm around his shoulder.

As we turned the corner to our street, we could hear something loud and rumbling. Jeeps. These ancient Russian military vehicles were a common sight in our neighbourhood, and the militia in them would yell at each other and taunt passers-by. It was all just intimidation, and it became a bit of a game to us. We would duck out of sight and pretend we were in a war film.