CONTENTS

COVER YA EARS

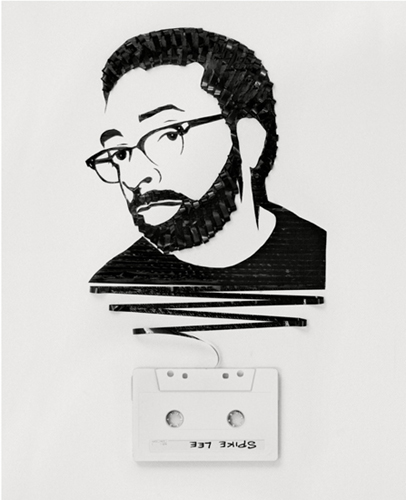

Growing up in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Cobble Hill in the mid-sixties I was first introduced to the power of portable music. There was this guy everybody called Joe Radio. He got that moniker because he stood on the corner of Henry and Warren Streets with a small transistor radio on his shoulder. I should say attached, because if you saw Joe Radio, you saw that small transistor on his shoulder. He would listen to the WMCA Good Guys or WABC with Cousin Brucie night and day, day and night. Joe Radio was the only one I ever knew who did that. The image of him constantly listening to his radio was burned into my mind at the young age of eight. Many, many years later, that boyhood experience reemerged as the character Radio Raheem in my 1989 film Do the Right Thing. I witnessed the tiny transistor radio evolve into the boomboxes of the eighties. I never owned one; number one reason, they weighed a ton; number two, it cost a fortune in batteries. I didnt have stock in Eveready or Duracell. It was some serious work lugging that shit around, and you had to have a strong will to impose your musical taste on the world. There was no sense in having a boombox if you did not play it at eardrum-shattering levels. You also had to be ready to fight if somebody dared ask you to turn that shit down. Radio Raheem would die for his boombox, for his music, blasting Public Enemys anthem Fight the Power all throughout the film.

This fine book by photographer Lyle Owerko superbly documents the long-gone era of the walking boombox (I never liked the racist term ghetto briefcase) in all its loud glory. These photographs bring back many memories, but do I miss them? Hell no. Thank God for Sonys Walkman, which eventually evolved into todays Apple iPod. Although, every once in a while, when driving my New York Yankeespinstriped Mustang in Marthas Vineyard (home to many fans of the hated Boston Red Sox), I blast Public Enemys Fight the Power and Radio Raheem lives.

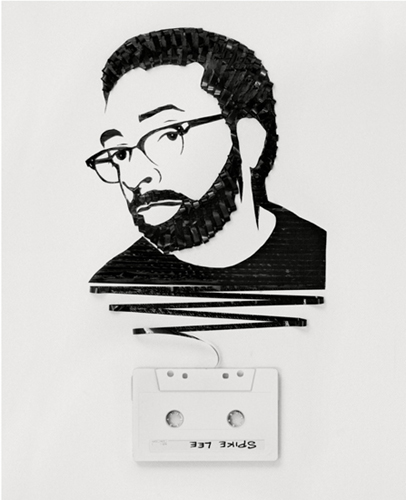

Spike Lee, March 20 in the Year of Our Lord 2009, Brooklyn, New York

PORTRAIT OF SPIKE LEE

ERICA SIMMONS

CONION C100F

AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS, NEW YORK CITY, 1989

OLIVIER MARTEL

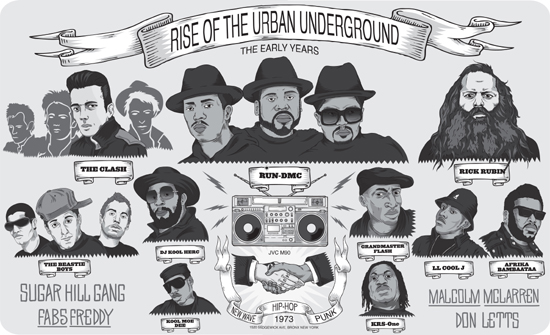

WEAPONS OF MASS DISTRACTION

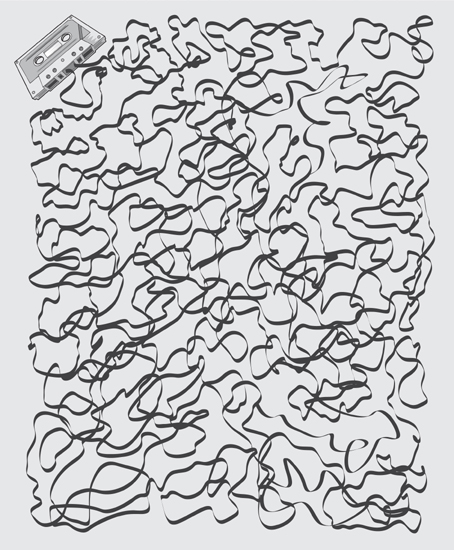

Ive always been fascinated with the meanings of things, more than just the visage of it. To me thats what makes long-lasting art. Thats what makes long-lasting history. Thats what makes anything that is culturally significant. It isnt just the visual of it. Its the meaning behind it and somehow thats how I found boomboxes (or more like boomboxes found me).

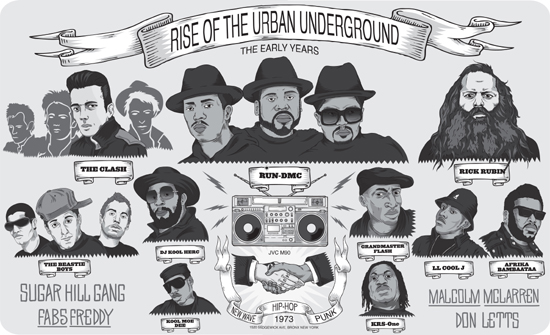

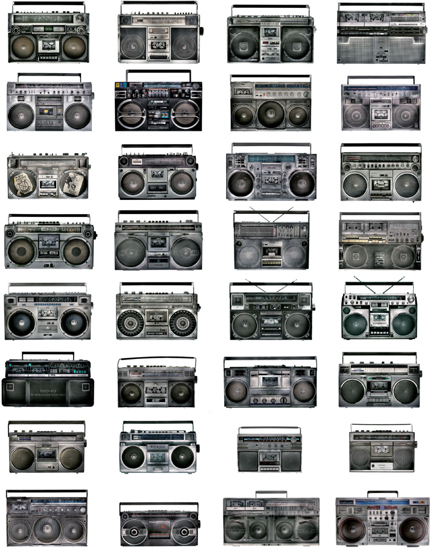

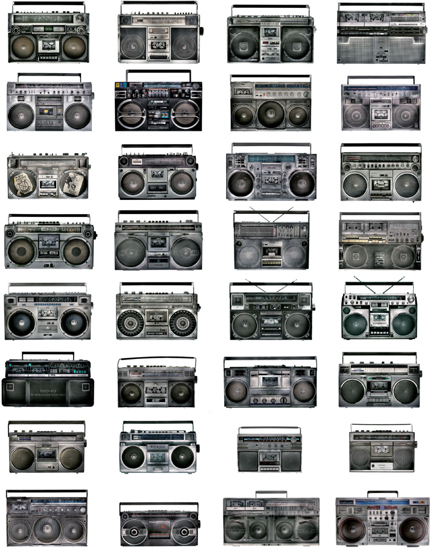

Exactly when the term boombox hit the streets is not known for sure. In the United States, department stores apparently began using the term in marketing and advertising as early as 1983. Street slang linguists pin the term down at 1981, and define the boombox as a large portable radio and tape player with two attached speakers. Initially, it became identified with certain segments of urban society, hence the nicknames like ghetto blaster and beatbox. And due to their size and relative portability, as the general public began to embrace these gargantuan creations of electronics, lights, and chrome-plated gadgetry, a new form of expression was born.

I was given my first box in the early eighties to listen to while I did my artwork. It was an upgrade from the one-speaker Realistic tape deck that I had been using to listen to mix tapes. Throughout college I worked in silk-screen shops, taking my boombox from gig to gig until it gradually was entirely covered with ink, paint, and caustic solvents. After college, I moved to New York and lived on Forty-first Street in an industrial building a few blocks from the center of Times Square. It wasnt long before I hit up one of the electronics shops in the area for an all black and shiny metallic-plated Lasonic box. That box stayed with me through many moves, different girlfriends, and some really odd living situations.

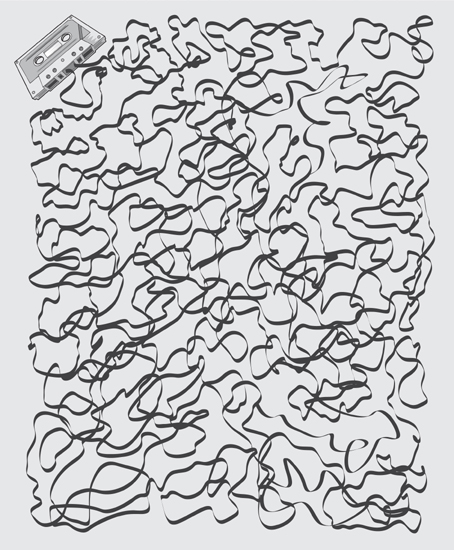

Over the years, I worked as a photographer in some pretty hairy situations, both in Africa and New York. After the events of 9/11 ripped apart my downtown neighborhood, I took every assignment I could to travel. In December of 01, I was in Japan on tour with the band American Hi-Fi, directing their tour documentary. During a few hours off in Tokyo, I lucked out in picking up an absolutely mint late-seventies Victor (JVC) at an outdoor marketI was stoked. It went everywhere with us. The band insisted on having it onstage with them, placed next to the drum kit at each nights gig. The box saw so much fun on that trip. On the last night of the tour, the band headlined at a huge venue in Tokyo with MTV Japan on hand to film the gig. Hi-Fi pulled out all the stops. The crowd went ballistic as the band rocked the joint. Stacy Jones, the lead singer, destroyed his Fender during the last encore, then turned and grabbed whatever he could get his hands on next... my boombox! It was sitting comfortably in front of the bass drum. He snatched it and in one quick swoop pummeled it into the stage like Godzilla swatting down a tiny fighter jet. I watched as my beautiful, mint-condition box was obliterated in a rock star crash test. Pieces were everywhere... a fractured rut was left in the stage. After the lights went up, I found my box and dragged its eviscerated remains backstage for one final photograph. Meanwhile, the venues bewildered road crew stood in a circle staring at the gaping hole in the stage that looked as if an asteroid had knifed through the ceiling and left a small impact crater.

The picture I took of the ruined remains of the box became the front of their live-in-Japan album called Rock n Roll Noodle Shopit made a great cover. After that I was determined to find another one like it. Fervid searches expanded my collection through flea markets and thrift stores, eventually leading me online to eBay, which gradually built the remainder of the collection that I have today.

This book grew out of a portrait series of my boombox collection that I began working on some years ago. I wanted to capture the physicality of nostalgia, of what had been a cohesive element between so many genres of music. Initially, I intended to create a photobook so other people could have a set of my work, a version of their own boombox collection. But as I spoke to friends about the project, the conversations we had made me realize that there was a much bigger story here. In documentary-style photos of boomboxes from the seventies and eighties, you always see groups of people hanging out around boxes on the street, in parks, and on subways, sharing their music. I kept hearing talk about a connection between the box and the ideals of empowerment and community.

Next page