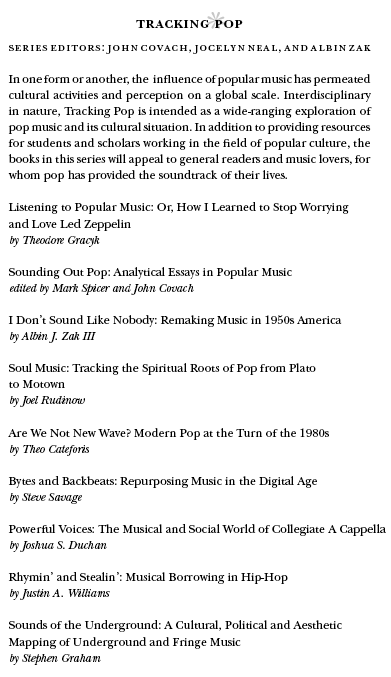

Contents

Guide

Page i

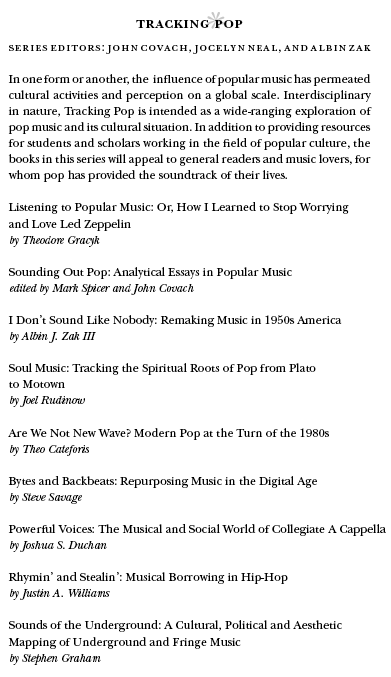

Sounds of the Underground

Page ii

Page iii

Sounds of the Underground

A Cultural, Political and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground and Fringe Music

Stephen Graham

University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

Page iv

Copyright 2016 by Stephen Graham

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-472-11975-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12164-9 (e-book)

Page v

Contents

Page vi Page vii

The underground is an enticing concept. It suggests ideas of shadowy struggle and esoteric doings, whether we think of wartime resistance in France, of the nineteenth-century Underground Railroad in the United States, or of any number of obscure cultural movements. Underground has long served as a potent metaphor, suggesting as it does concealment, dissidence, and subversion. Cultural and political movements around the world have noticed this; right-wing extremist groups such as National Socialist Underground and leftist organizations like Weather Underground have eagerly seized upon underground as a readymade label implying stealth subversion and dissenting resistance.

Music has been no exception, with underground being adopted by practitioners and accorded by critics across many different genres as a marker of cultural distinction. Use of the term typically follows a loose sort of logic. Underground hip-hop or dance musics, for example, are positioned as distinct from supposedly compromised commercial forms (straight from the underground!). This is a kind of relative use of underground that plays on the terms suggestions of subversion and distinction. I have something different in mind in this book, even if Im also calling up suggestions of obscurity and, to a point, subversion.

Im writing specifically about noncommercial forms of music making that exist in a kind of loosely integrated cultural space on the fringes and outside mainstream pop and classical genres. What Ill call underground musical formsnoise, improv, and extreme metal but also fringe practices like post-noise experimental pop and even some kinds of sound artshare a world of practitioners burrowing away independent of mainstream culture. They may be trying to resist that culture politically, but they might also just be satisfying themselves by making music for small audiences and little to no profit.

My argument here is that due to shared practical, musical, and in many Page viii cases political allegiances, these practices can be described collectively using the guiding metaphors of the underground and the fringe. The first describes ultra-marginal music and the second closely related music that fringes onto either high-art institutions or the commercial marketplace. I use critical analysis and interviews with practitioners in drawing up a map of this broad territory. Those interviews are dotted throughout the book but concentrated across Part II, which develops the contextual introduction of Part I ahead of the closer focus on music in Part III.

This expansive and seemingly definitive organizing framework is used even while acknowledging that my version of the underground and its fringes is personal and partial. Im offering a set of signposts rather than a hard proof, a starting point rather than a destination. There are other undergrounds, just as there other versions of this particular underground. Im simply trying to provide some useful categories and details and in this way to open up conversation and spur further thought about a desperately neglected realm of musical activity.

Page 1

What Is the Underground?

Page 2 Page 3

Introduction to the Underground and Its Fringes

1.1. Introduction: Contexts, Chronology, and Concepts

Ive become used to bizarre sights and sounds. Men playing guitars with their teeth against a backdrop of murderous imagery. People bumping into each other in confused but cheerful huddles, trying to follow vague instructions written on cards. A woman covered in synthetic blood screaming into a microphone like a loosed warrior. A piece of amplified soft glass being eaten, spectacularly. These kinds of experiences are now routine to me. And similar things can be found in obscure or veiled places across the world, from basement rooms in rented accommodations in Detroit, to repurposed bars and clubs in Dublin or Berlin, to meetinghouses in Tokyo, to scrungy warehouses in London and Glasgow. At venues such as these concerts and festivals are held where sheets of paper are played with handheld fans and cymbals with violin bows, where contact microphones expose the hidden sounds of the most basic acts of friction, where turntables are mined for sound without the use of records, and where abrasive sonic tinkering and wild and sometimes rickety experiment is the order of the day.

This book is about all of these things. It tries to construct a map that might organize all of this activity and present it in some intelligible scholarly form based on a couple of key guiding metaphors, understanding the dangers inherent to this institutionalizing impulse all the same. It focuses on what I am calling underground music, an umbrella term for the musical practices just described. These practices incorporate both ultra-marginal underground Page 4 music and underground music that fringes onto either more mainstream commercial or high-culture contexts. This fringe music can be seen in the case of the commercial fringe, for example, with artists such as Ben Frost and Laurel Halo making experimental electronic music and with semipopular festivals such as Roadburn in the Netherlands, Villette Sonique in France, and All Tomorrows Parties in the United States and the UK. On the other hand, high-cultural fringe music can be seen with groups like Skogen and Polwechsel that fuse improvisation with contemporary classical music techniques. But for the most part, underground practices exist at something of a remove from the mainstream, underground.

The ultra-marginal underground can be seen in noise artists such as Werewolf Jerusalem, the New Blockaders, Prurient, Hijokaidan, SPK, and Ramleh; in more or less obscure black metal artists such as Lord Foul, Leviathan, Wolok, and Xasthur; and in improvisers such as Okkyung Lee, Maggie Nicols, Annette Krebs, and Axel Drner. These artists make work that sometimes gets programmed in the same venues and festivals; often gets written about in the same places; and, broadly speaking, operates in the same kind of exploratory cultural tradition where techniques and sounds both from high-art and popular forms, from free jazz to metal to techno and jungle, are variously important. The shared radical aesthetics and cultural marginality of these musics places them into some kind of continuum, notwithstanding important subcultural genre differences between them; extreme metal has its own scene economies when placed against, say, improv, as noise does likewise. But these dont cancel out the many cultural, aesthetic, and political interrelations we can see across these musics. Weve long had words, however imperfect, to describe classical and popular and traditional musics. But my argument here is that we need a new term to supplement these monolithic categories in order to describe (and, yes, effectively institutionalize) the activity that falls between their cracks.

Page iii

Page iii