Foreword

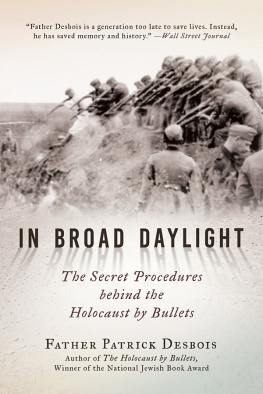

One thing I remember learning at school is that there is no word in ancient Hebrew for history. In its place is the word zikaron . Im not sure why this piece of information has stuck with me over the years, but it has. I remember my teacher explaining that the literal translation of zikaron is memory, but that something is lacking in this translation. There is something about the words meaning that just cannot be conveyed in the English language, she said.

Perhaps this is because history and memory are indistinguishable in Judaism. The Jewish past is not understood as a series of events arranged in chronological order, but as a continuous tradition. To be part of Jewish history is to practise the Jewish tradition, and to find meaning in that tradition is to become part of a shared memory. Zikaron is not just the recollection of past experiences; it is also the communal memory of an entire way of life.

I was reminded of this word when I started working with Eva Slonim on her memoirs. Every Tuesday, for around four months, we would sit together in her study and talk about her past. I was amazed by the facility of Evas memory; I often had to remind myself that she was only twelve or thirteen years old when most of these events took place. I was in awe of her ability to remain focused and composed while talking about moments of unimaginable suffering, of complete horror. She told me her story with perfect stoicism, almost as if it were someone elses.

I recorded all our conversations; listening back to them, as I later did, was more gut-wrenching than the conversations themselves. When I was not in Evas warm and reassuring presence, I found the evil she encountered as a child overwhelming and incomprehensible.

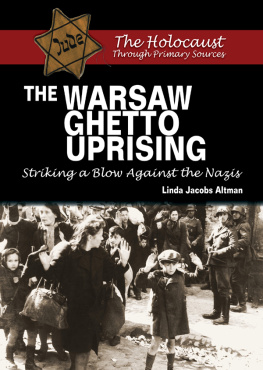

It was when I started transcribing our conversations that I really heard the voice of the young Eva. I was seeing and experiencing history through a childs eyes. There has been such a huge emphasis on systematically archiving what happened during the Holocaust. This is of course necessary, but sometimes it can make history look like cold, hard facts, and the sounds of individual suffering can be swallowed up.

Eva and I spoke at length about why she wanted to write this book. One theme we continuously came back to was testimony. Eva is driven by a sense of responsibility to tell future generations about what happened to her and her family. She wants to teach her grandchildren about Jewish life before the Holocaust, to ennoble the idea of Jewish continuity, and to teach and warn the world at large about humanitys potential for evil.

I once suggested to Eva that another function of testimony is more personal. It allows individuals the opportunity to reflect on what has happened to them. It may offer catharsis or a sense of release, perhaps even a new perspective from which to interpret their past experiences.

Eva shook her head. No, she said. There is no meaning in these memories. Reliving these memories is only difficult. Im doing it for the next generation.

When you read this book, then, you will hear two voices. One is Eva as we know her now, a historian speaking with the caution and guardedness of someone who has built an internal wall against extraordinary suffering. The other is the Eva who experienced this trauma for the first time, the one who remembers, the girl who first interpreted her experiences with the naivety and innocence of childhood.

In Evas testimony history and memory are entwined in one expression. It is almost impossible now to interpret anything meaningful from what happened to Eva. The Holocaust still looms as a break from tradition, a fracture in Jewish history in Evas words, the final goodbye to an entire way of life.

These memoirs are, first and foremost, an exercise of incredible courage. I believe this courage comes from Evas knowledge that her story will be recorded. She writes for zikaron , the hope that, sometime in the future, her testimony along with those of her peers will become part of the Jewish tradition, told over and over, lived over and over. This record of a personal memory will become part of the shared memory of the Jewish people.

Oscar Schwartz

Readers will find a glossary of the foreign-language terms used in this book on pages 178180.

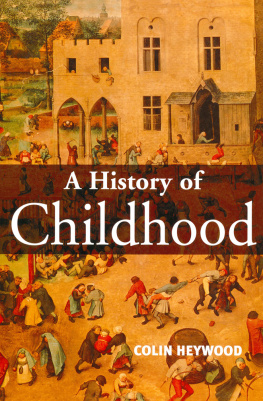

Childhood

PALISDY ULICA, BRATISLAVA, EARLY 1930S

In spite of everything, I remember Bratislava as a beautiful city. The Danube flows through it majestically. I remember how, on sunny days, we would cross the river by boat, or by bridge, and go to the parkland on the other side for picnics.

I was born in Bratislava on 29 August 1931, the second child of Eugene and Margaret Weiss. Their first child, Kurti, was their only son, my only brother. He was one year older than me, the only boy in our budding family. After me, my mother would give birth to another eight girls Noemi, Marta, Esther, Judith, Renata, Ruth, Rosanna and Hannah all born in almost yearly succession.

We lived in a grand three-storey apartment building. It stood tall and imposing opposite the presidents palace. I remember it well: number sixty, Palisdy Ulica.

My Papa bought Palisdy 60 before he married my Mutti, Margaret Kerpel. I believe that their marriage was arranged, and that their wedding was held in Mattersburg, Austria Muttis birthplace in 1929. Papa would have been twenty-six when they got married, and Mutti was two years younger.

Young men werent supposed to get married until they had the means to provide for a family. Before Papa got married, he matriculated and started a successful textiles business. Papa would work all day and then travel at night to the various places that his business would take him, while studying accountancy and textile engineering part-time. He was enterprising, and tireless in his efforts to pass on this work ethic to his children.

During summer we would go for holidays in the Tatra Mountains, staying at a Jewish resort in ubocha. It was an elegant place, and kosher. Fresh rolls were baked every day. Tall trees and mountains surrounded the hotel. Papa would always arrive late for our holidays; there was always some outstanding business matter that had to be attended to.

We girls used to race down the hillside, rolling all the way to the bottom. Noemi and I would compete to see who could eat more bread rolls. Papa used to watch us and pay us one crown for every roll we ate. Kurti was a reserved young boy and preferred to read on his own. Our younger sister Marta was a cute little girl with a fiery disposition. I remember an adult once said to her, You are so sweet I could eat you up, and she replied, Gobble up your own children! In ubocha there was also a swimming pool, and we little ones were permitted to swim even though there was mixed swimming.