Table of Contents

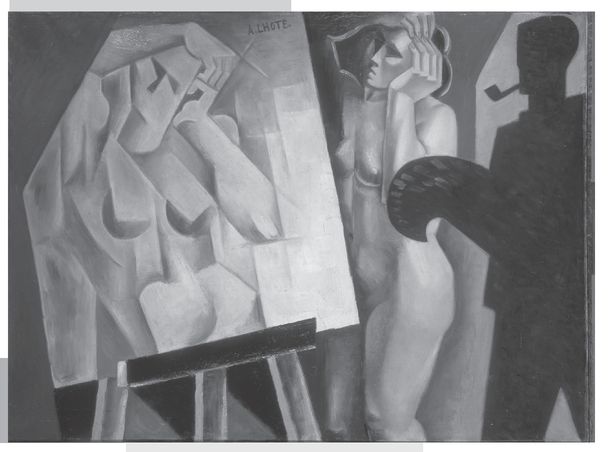

Le peintre et son modle (1920) by Andr LHote demonstrates the relationship between cubism and abstract mathematical ideas of transformations. (CENTRE POMPIDOU, PARIS)

Also by Amir D. Aczel

Chance

Descartess Secret Notebook

The Mystery of the Aleph

Pendulum

Entanglement

The Riddle of the Compass

Gods Equation

Fermats Last Theorem

For Miriam, with much love

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I AM HIGHLY INDEBTED to five mathematicians and one artist. They are the mathematicians Pierre Cartier (IHES and ENS, Paris), Barry Mazur (Harvard University), Marina Ville (Jussieu, Paris, and Boston), two mathematicians who insist on anonymity, and the painter Thomas Barron.

I thank Owen Gingerich and the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University for making me a visiting scholar in the department. I am equally indebted to Fred Tauber, director of the Center for Philosophy and History of Science at Boston University, for having me as a research fellow at the center.

I thank my longtime editor and friend, John Oakes, for making this book a reality and for his ever thoughtful editing and advice. Finally, my deepest appreciation to my wife, Debra, without whom this book would never have been written.

one

THE DISAPPEARANCE

IN AUGUST 1991, Alexandre Grothendieck, widely viewed as the most visionary mathematician of the twentieth century, a man with insight so deep and a mind so penetrating that he has often been compared with Albert Einstein, suddenly burned 25,000 pages of his original mathematical writings. Then, without telling a soul, he left his house and disappeared into the Pyrenees.

Twice during the mid-1990s Grothendieck briefly met with a couple of mathematicians who had discovered his hiding place high in these rugged and heavily wooded mountains separating France from Spain. But soon he severed even these new ties with the outside world and disappeared again into the wilderness. And for ten years now, no one has reported seeing him. His mail keeps piling up uncollected at the mathematics department of the University of Montpellier in southern France, the last academic institution with which he had been associated. The few individuals whom he had once trusted to forward him the select pieces of mail he did want to receive no longer have any way of making contact with him. His children have not heard from him in many years, and two of his relatives who live in southwest Francenot far from the Pyreneesand with whom he had had limited, sporadic contact, have not had a word from him in years. They do not even know whether he is still alive. It seems as if Alexandre Grothendieck has simply vanished off the face of the earth.

During his most active period as a mathematician, from the 1950s to around 1970, a period when he completely reworked important areas of modern mathematics, lectured extensively on his pathbreaking research, organized leading seminars, and interacted with the most important mathematicians from around the world, Alexandre Grothendieck had been closely associated with the work of Nicolas Bourbaki. And some have surmised that Grothendiecks inexplicable disappearance into the Pyrenees was somehow connected with his relationship with Bourbaki.

Nicolas Bourbaki was the greatest mathematician of the twentieth century. Since his appearance on the world stage in the 1930s, and until his declining years as the century drew to a close, Bourbaki has changed the way we think about mathematics and, through it, about the world around us. Nicolas Bourbaki is responsible for the emergence of the New Math that swept through American education in the middle of the century as well as the educational systems of other nations; he is credited with the introduction of rigor into mathematics; and he was the originator for the modern concept of a mathematical proof. Furthermore, the many volumes of Bourbakis published treatise on the elements of mathematics form a towering foundation for much of the modern mathematics we do today. It can be said that no working mathematician in the world today is free of the influence of the seminal work of Nicolas Bourbaki.

But what was the nature of the relationship between Bourbaki and Alexandre Grothendieck, and who is Nicolas Bourbaki?

ALEXANDRE GROTHENDIECK WAS born in Berlin on March 28, 1928, to Alexander (Sacha) Shapiro and Johanna (Hanka) Grothendieck. Both parents were ardent and very active anarchists.

Sacha Shapiro was born on October 11, 1889, to a religious Jewish family belonging to the Hassidic movement, in the town of Novozybkov in the region where the three borders of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia all meet. At times, the town has been Russian, at others, Ukrainian.

Shapiro forsook the Hassidic lifestyle of his parents and was swept with the revolutionary movements of the time. He participated in several uprisings against the Russian tsar, the first one being the abortive 1905 revolution. As a member of an anarchist movement, he took the nom de guerre Sacha Piotr. He was first arrested when he was only sixteen years old, when the attempted coup against the tsar failed. Following this arrest, Shapiro was deported to Siberia and spent ten years in jail. Released in 1917, he found himself taking part in the Russian revolution that same year. Again he was arrested, and at some point was condemned to death. He escaped, was recaptured, and ran away again. During his last escape from the Russian police he lost an arm. He then fled from Russia, assuming the false name Alexander Taranoff, and would remain a stateless person for the rest of his life. Soon after his release from prison, before taking flight, he met and married a Jewish woman named Rachel, and with her had a son named Dodek.

But their time together did not last long and, with the aid of woman named Lia, he slipped across the Russian border into Poland. He and Lia then drifted through France, Belgium, and Germany, illegally crossing national borders with unusual agility, and finally arrived in Paris, where they lived together for two years; but Sacha had a string of other relationships with women. Through his anarchist activities he met important figures of world revolutionary movements, including the Americans Alexander Berkman (1870-1936) and Emma Goldman (1869-1940). He moved to Berlin and there, through his involvement with anarchist groups, met Hanka Grothendieck.

Johanna (Hanka) Grothendieck was born in Hamburg on February 23, 1900, to Albert and Anna Grothendieck. Albert had a shoeshine business in town, which at the height of his career he owned; otherwise, he worked there as an employee. Hanka was close to her father, who encouraged her to pursue her gifts of acting and writing.

Soon, the girl rebelled against her parents and her lower-middle-class upbringing and took up with artists and intellectuals. She hoped to become a writer, and early on in her life she worked as an editor and writer for small papers, and also studied to become an actress. She met and worked for German impressionist painters before the urge to travel swept her away from Hamburg and took her to the center of German intellectual life: Berlin.