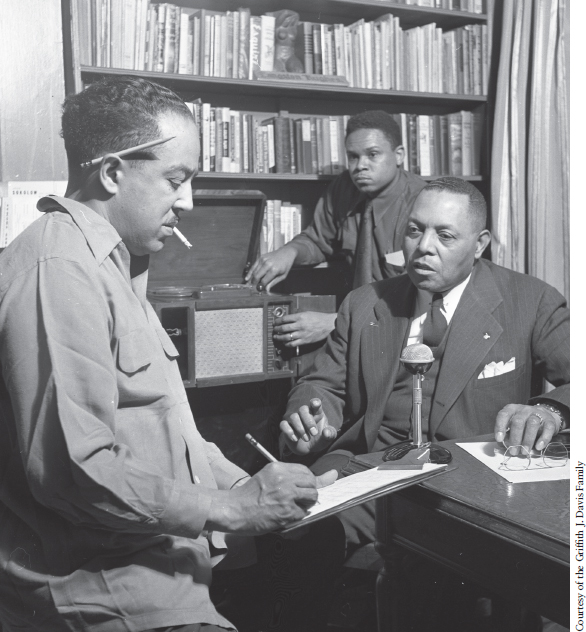

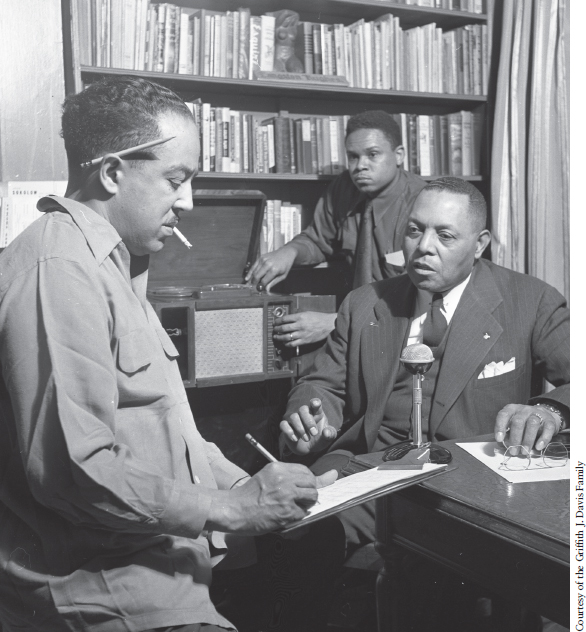

Samuel Battle speaks with famed poet Langston Hughes (left) for a never-published biography, as Hughes's secretary, Nate White, records the interview.

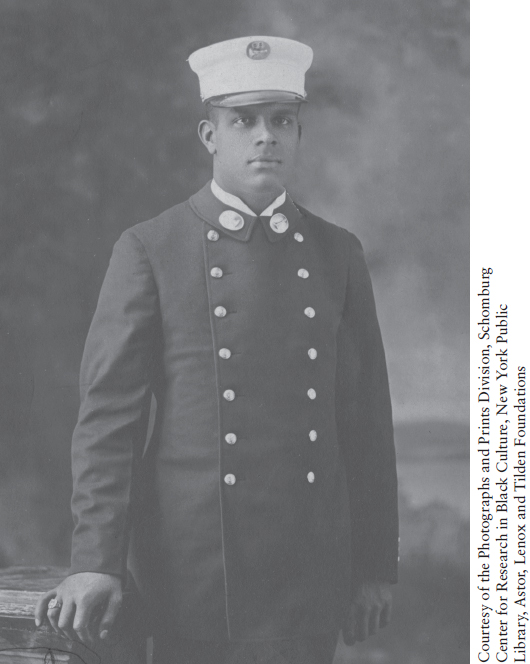

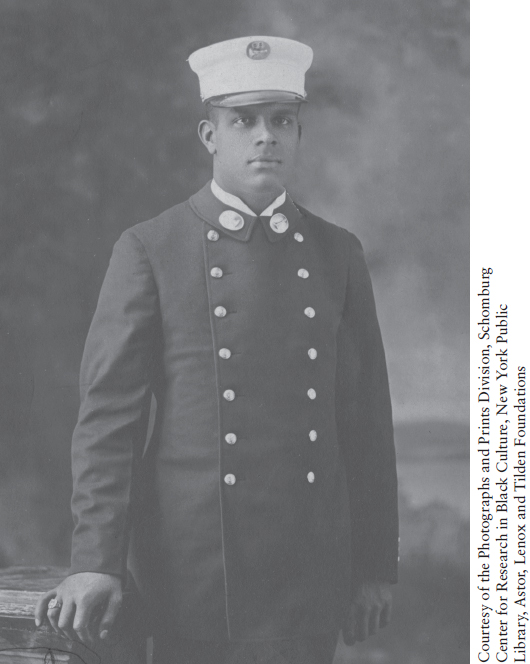

Renowned for feats of strength, Battle's protg, Wesley Williams, fought his way up the ranks of the New York Fire Department with the help of his father, James the Chief Williams, head of the Grand Central Station Red Caps. Lieutenant Wesley Williams (left) in 1927.

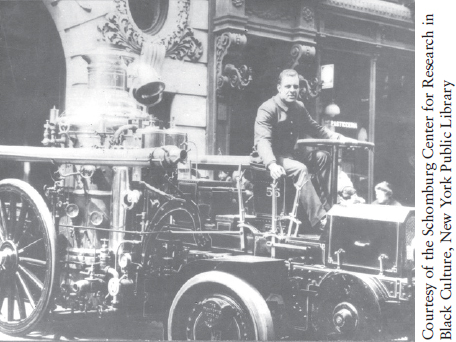

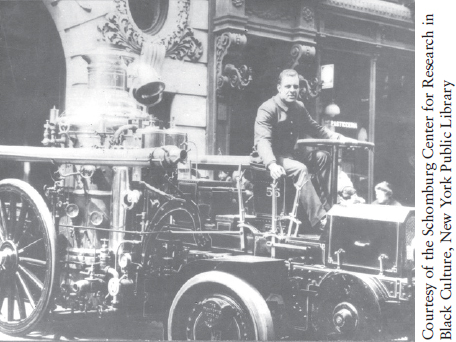

Wesley Williams started as a pumper crewman in 1919.

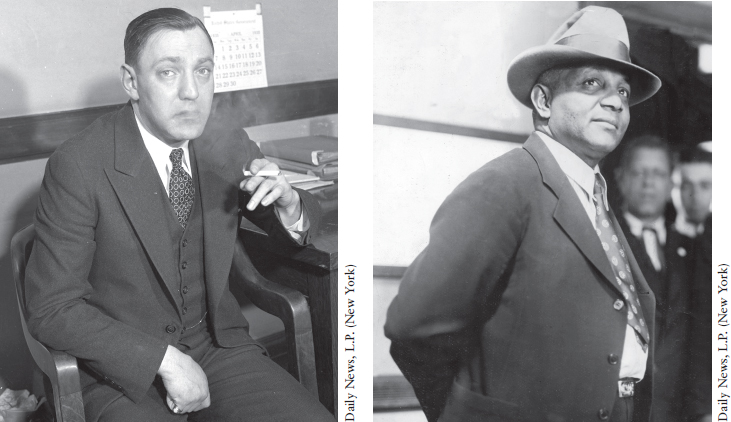

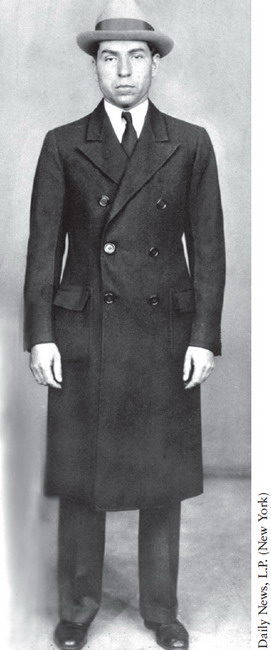

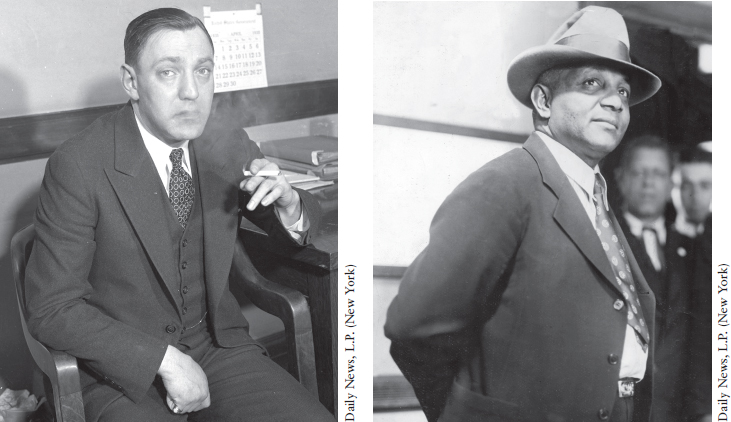

Democratic Party boss Jimmy Hines exacted revenge after Battle raided a gambling den run by Harlem cabaret king Baron Wilkins in 1923.

Battle cracked the case when mobster Dutch Schultz (left) had Harlem gambling kingpin Casper Holstein kidnapped in 1928.

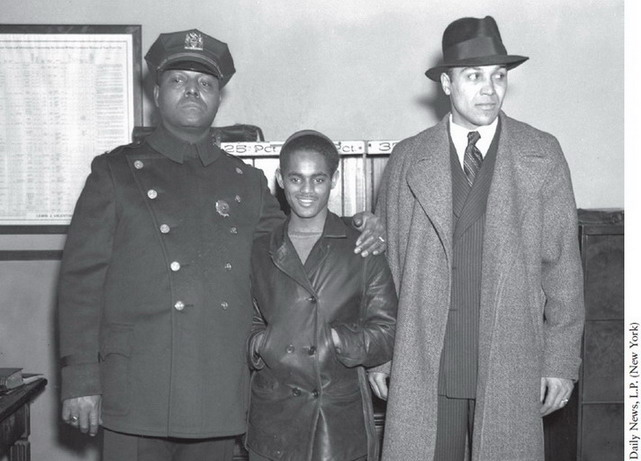

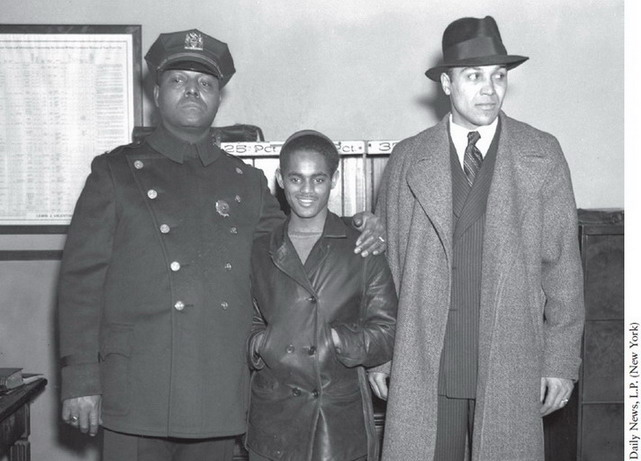

When rioting swept Harlem in 1935, sparked by false rumors that police had killed a black teenager, Battle and a detective posed with Lino Rivera to prove that the young man allegedly at the center of the violence was alive.

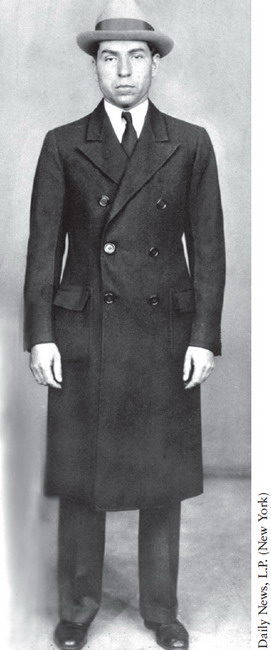

During Prohibition, Battle raided speakeasies while gangster Lucky Luciano lavishly paid New York Police Department brass for protection.

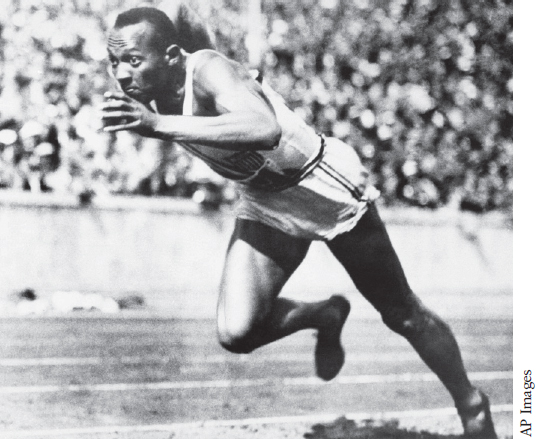

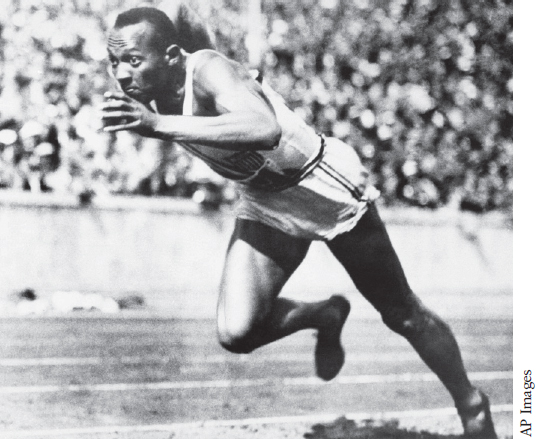

Jesse Owens took up lodgings in Battle's townhouse after Owens stunned Adolf Hitler by winning four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt impressed Battle indelibly at a public event in 1943, and she became an admiring friend.

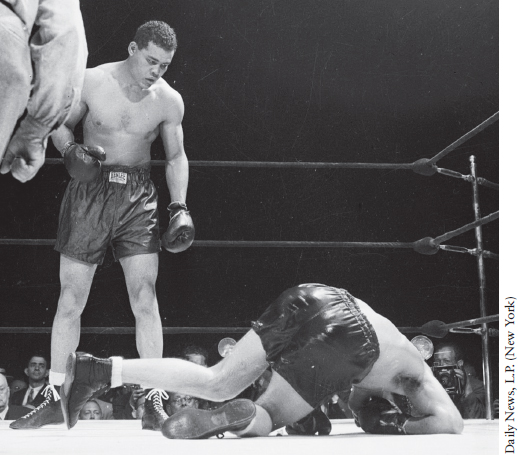

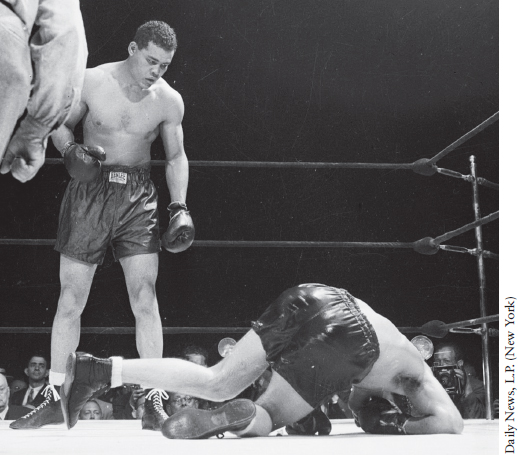

Battle was in Joe Louis's corner the night the Brown Bomber defeated Billy Conn to keep the heavyweight crown in 1941.

Battle became the first African American member of the New York City Parole Commission in 1941. Family members attended his City Hall swearing-in: (left to right) son, Carroll; Carroll's wife, Edith; granddaughter, Yvonne, held by Battle; wife, Florence; and daughter, Charline Cherot, mother of Yvonne. Battle took the post previously held by Lou Gehrig.

Florence Carrington married Battle at age sixteen, in 1905. She anchored their family and supported her husband through all his many struggles. Here she is with Battle on the steps of their Strivers Row townhouse, around 1945.

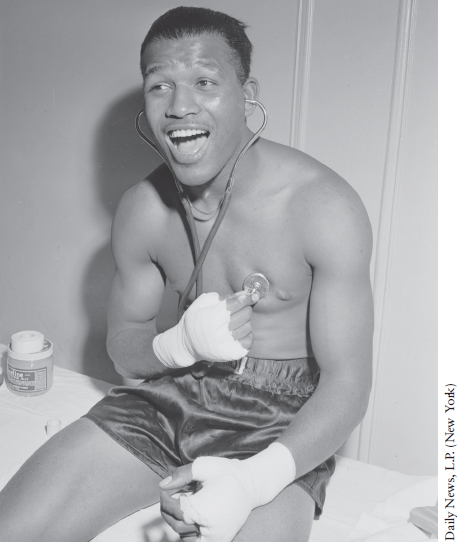

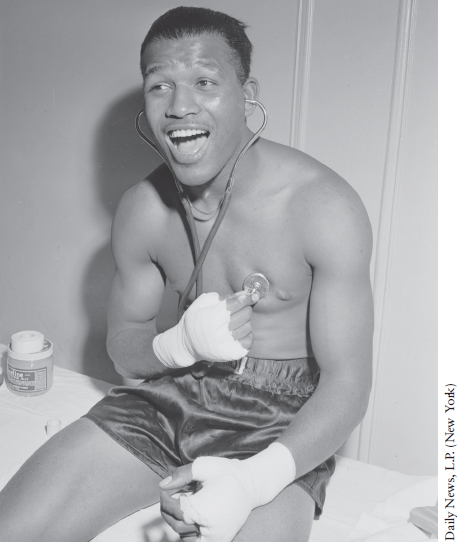

Battle mentored young Sugar Ray Robinson and remained the champ's friend for life.

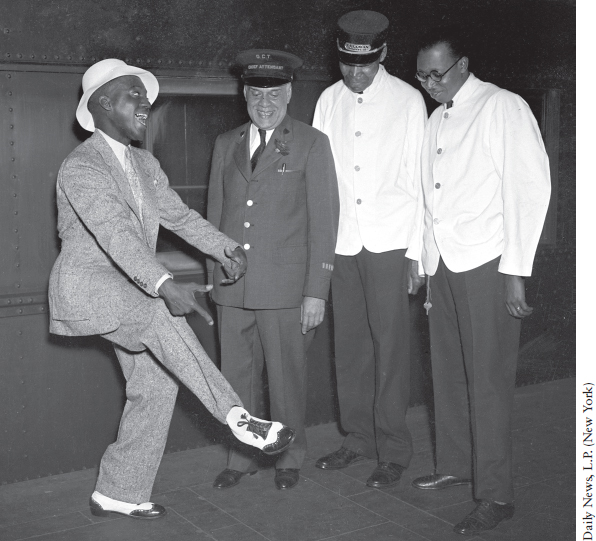

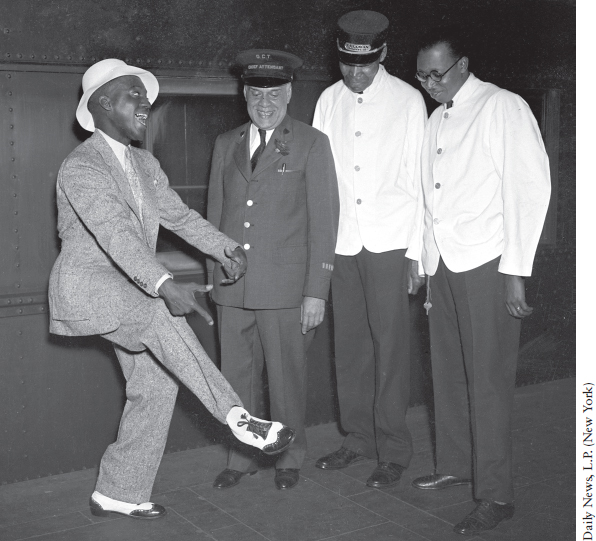

When his good friend the tap dancer Bill Bojangles Robinson died in 1949, Battle helped plan the dancer's funeral in Ed Sullivan's apartment. Robinson is seen here dancing for Chief James Williams (second from left), father of Wesley.

Rioting swept Harlem in 1943 after a police officer shot and wounded a black soldier, who was falsely reported killed. Mayor La Guardia summoned Battle to help restore peace.

Battle's grandson Tony Cherot (second left) with Councilwoman Inez Dickens (left) and New York Police Commissioner Ray Kelly (right) at a 2009 ceremony renaming the Harlem intersection where Battle saved a white officer's life in 1919.

PREFACE

THE HEART OF ONE RIGHTEOUS MAN

AN EARLY READER of this portrait of Samuel Jesse Battle harkened back to the Old Testament, verse three of Psalm 106: Blessed are they who observe justice, who do righteousness at all times! The connection was fitting. Battles enormous courage, seemingly limitless charity, and unfailing insistence on dignity far exceeded his human flaws. He would not be told no when no was unjust. Expecting equal treatmentand occasionally paying dearly for his good faithhe persevered to prevail over some of New Yorks most closely guarded racial barriers.

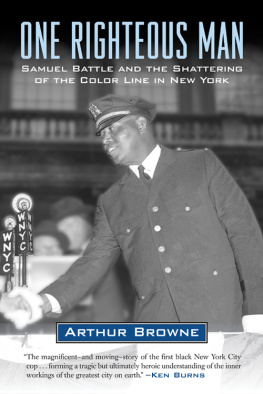

The moral bearing that propelled Battles victories shines most vividly through his own words. In 1949, he hired Langston Hughes to write his autobiography, spent hours speaking with the renowned Harlem Renaissance poet, and provided him with handwritten recollections. The result was a never-published, eighty-thousand-word book titled Battle of Harlem. One copy of the manuscript resides among Hughess papers at Yale Universitys Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Battles grandson Tony Cherot has custody of a second copy. The two are not identical. After publishers showed no interest, Battle worked with a new partner in hope of making the book more marketable. He also secured a foreword by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

All to no avail.

Relying on Cherots copy of the revised manuscript, I set out to bring Battle to life in contexts that stretched from the postCivil War South through turn-of-the-century New York, through his fight to join the New York Police Department, through the Roaring Twenties and Prohibition, through the glorious rise and tragic fall of Harlem, through the Great Depression and two world wars. From his rambunctious boyhood in 1880s rural North Carolina to his death in Harlem in 1966, Battle was so engaged in his times that his journey illuminates the sagas of the United States and its largest city as oppressively experienced by African American citizens.

To the extent that I have succeeded in capturing the man and his eras, I owe a debt of gratitude to scholars and authors who documented the countrys social, cultural, political, economic, sporting, and military evolutions. As but two examples, Gilbert Osofskys