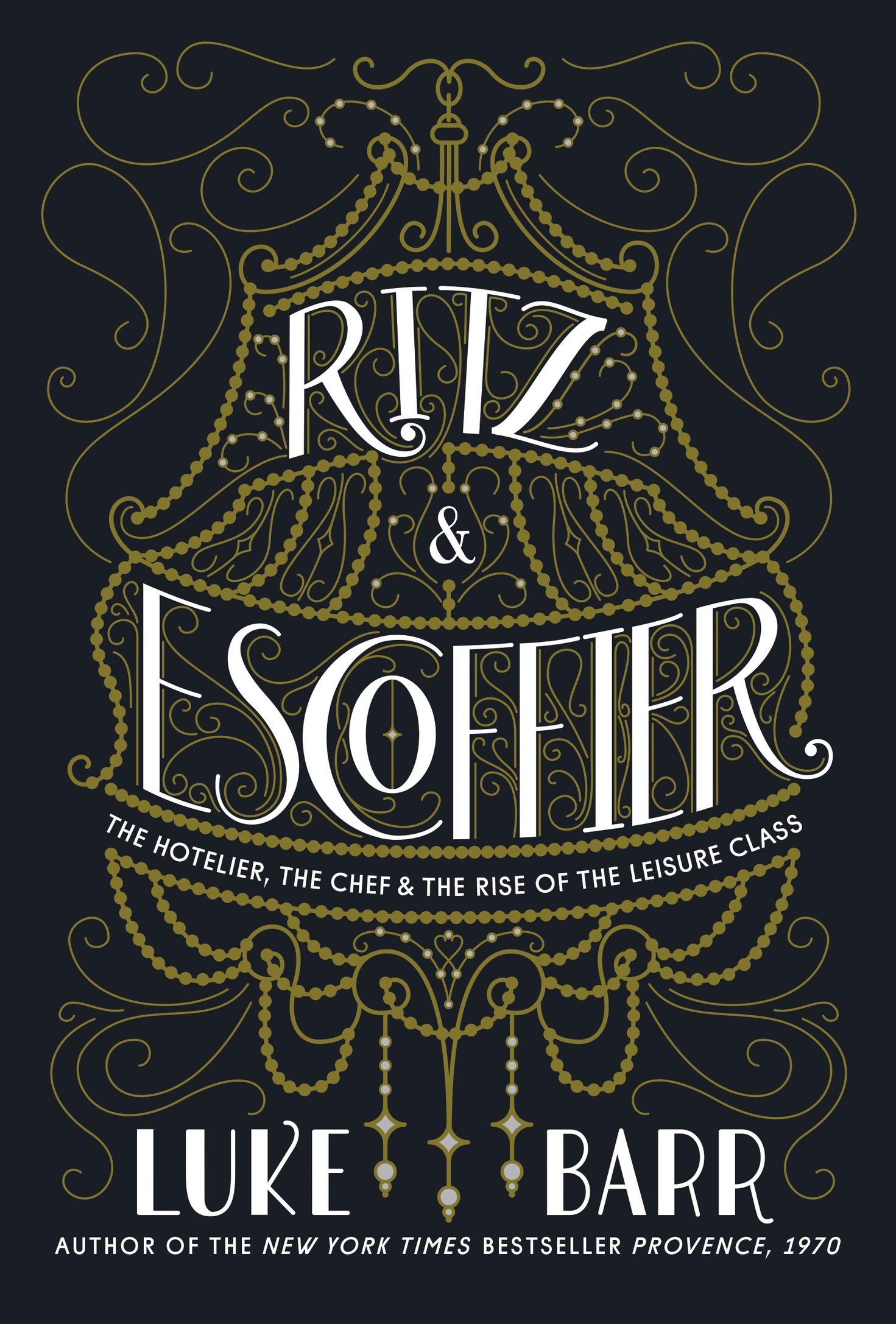

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Barr, Luke, author.

Title: Ritz & Escoffier : the hotelier, the chef, and the rise of the leisure class / Luke Barr.

Description: First edition. | New York : Clarkson Potter/Publishers, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015344 | ISBN 9780804186292 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780804186308 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ritz, Csar, 18501918. | Escoffier, A. (Auguste), 18461935. | Savoy Hotel (London, England)History. | Hospitality industrySocial aspectsHistory19th century. | Hospitality industrySocial aspectsHistory20th century. | Leisure class.

1

THE HOTELIER and the IMPRESARIO

In early August 1889, Csar Ritz left Cannes on an overnight train, the 8:43 p.m. bound for Calais. He was en route to London, ensconced in a private cabin, traveling alone.

He wore a suit with a high-collared shirt, a tie and waistcoat, and a bowler hat. As usual, he was dressed impeccably, a white carnation in his lapel, his moustache carefully waxed. Ritz was a young man, but his hairline had begun to recede above his high brow and intelligent, watchful eyes. He looked around the compact cabin: it was wood-paneled, with brass coat hooks, a mirror, and a number of storage compartments for his personal items. (His trunk had been taken by a porter when he boarded the train.) Now Ritz hung his jacket in the small closet and placed his hat on the rack. The weather was hot, and he was glad to be traveling at night.

Ritz loved to travel, the thrill and speed of it, the trains rushing toward the future. The Calais-Mediterranean Express train he was on now, for example, had launched a few years earlier, in 1886, and was state of the art, with a restaurant car and onboard lavatories, precluding the need for rest stops at stations along the way. The train ran slowly along the French Riviera, stopping at resort towns like Menton and Monte Carlo before speeding north through Lyon and Paris and on to the English Channel. From there, Ritz would board a ferry and then another train, to London. The trip would take a full night and day.

It was remarkably fast, Ritz thought. The express trains were transforming European travel and, especially, the towns along the Mediterranean. The English had been coming to the Cte dAzur for a century already, traveling by carriage and on boats. Rail lines had made the trip far easier. There were numerous competing train companies using the tracksthe long-established Marseilles-to-Nice service along the coast dated back to the 1860s, which was when the Cannes station had been built, a small white building with a roof covering both tracks. But the express trains heralded a new era, bringing throngs of visitors from all over Europe. This was good for Ritz: he was in the hotel business.

Why was he going to London, anyway? He hated London. Well, hed never been to London, actually, but he hated the idea of it: the gloom, the fog, the dour English propriety and cool reserve. The mediocre food. He was Continental, in every sense of the word. His business was pleasure. Ritz was a hotel man, welcoming guests with well-practiced charm at his two small properties, one in Cannes, the Htel de Provence, the other in Baden-Baden, Germany, the Hotel Minerva, where he also ran the Restaurant de la Conversation.

He was thirty-nine years old and had been working in the business his whole lifein Lucerne, Paris, and Vienna; in San Remo, Monte Carlo, and Trouville; all over Europe, following the glamorous trail of vacationing aristocrats and wealthy tourists as they took their cures and baths and sought mountain air in the summer and Mediterranean sun in winter. They were an international tribe, increasingly mobilethe Orient Express, with its luxurious sleeping cars, had just launched the first nonstop train between Paris and Constantinopleand Ritz had cultivated a following among them. The dapper young Swiss hotelier was effortlessly multilingual (if heavily accented), and never forgot a name or a face. Not only that, he also took careful note of his clients whims and desires: who preferred what for breakfast, who required a carafe of water on his bedside table at night.

Ritz was also a showman, an orchestrator of evening entertainments and gala dinners. Indeed, it was because of one such grand dinner that he now found himself, however reluctantly, on the train to London.

It had been almost a year ago, that dinner, at Ritzs recently opened restaurant in Baden-Baden. The Restaurant de la Conversation was already the talk of the town. He had advertised both the hotel and restaurant extensively, printing lavish brochures, and installed electric lights above the terrace, twinkling in the branches of the plants and trees. He was soon attracting a glamorous crowd. (Kaiser Wilhelm I, the German emperor, had eaten dinner there, and Ritz had made sure everyone knew it.) Baden-Baden was a summer resort, a place people came to for the casinos and the racetrack, and of course for the hot-spring bathsbaden is German for bathand it was a town where, in the evening, elaborate dinner parties were held. So when Prince Radziwill, a leading member of the Kaisers circle and Berlin society, told Ritz that he wanted to host a dinner that would be rememberedsomething original, he saidand that cost was not a concern, Ritz seized the opportunity.

This was the sort of challenge Ritz loved: to create a spectacle. And all the better to do so with an unlimited budget. This would be more than a dinner; it would be an event. He landed upon a simple, summery idea: to bring the outside in. He covered the entire floor of the restaurant with grass, and the walls with roses, hundreds and hundreds of them. He placed potted trees among the tables and brought a stone fountain and pool into the restaurant and filled it with exotic goldfish. At the center of this theatrical indoor woodland scene was an enormous fern. Ritz had seen it at one of the local horticultural gardens and managed to rent it for the night. (That alone had cost a small fortune.) Then he built a table around the towering plant and covered that with yet more flowers. (Ritz was a great believer in flowersvast, extravagant quantities of them. He sometimes thought he was singlehandedly keeping the local florists in business.)