For my family,

the living and the dead

Contents

The pagination of this electronic edition does not match the edition from which it was created. To locate a specific image, please use the search feature of your ebook reader.

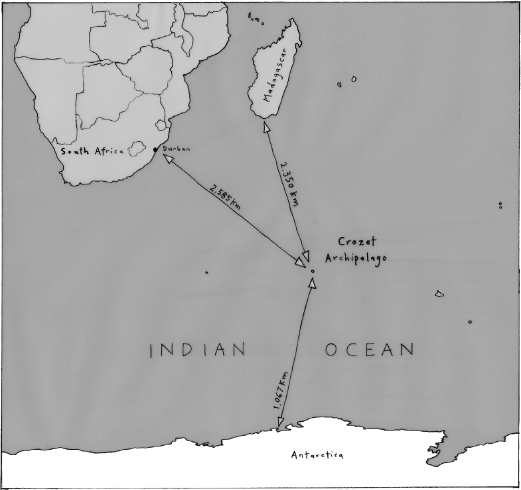

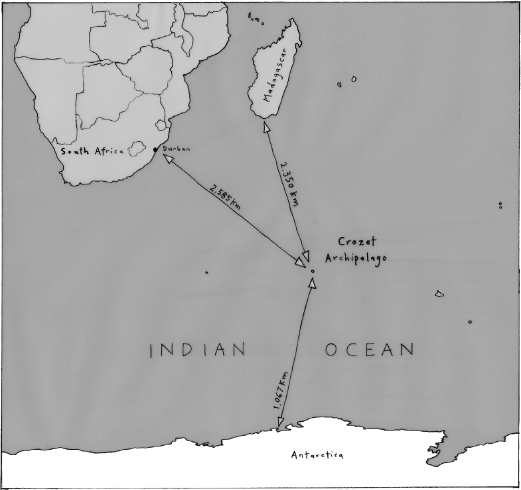

| The Crozet Islands, location | xii |

| The whales tooth carved by Charlie Wordsworth | 2 |

| Fanny Wordsworth | 10 |

| The Wordsworths commonplace book | 12 |

| A page from Fannys notebook | 15 |

| Fannys husband, Samuel Wordsworth | 23 |

| Spylaw House | 25 |

| Charlie Wordsworth as a young boy | 28 |

| Charlie as a young man | 30 |

| Charlie Wordsworth, schoolboy rambler | 38 |

| Fifteen-year-old Charlies certificate | 41 |

| The Strathmore, lying in the Tay River | 52 |

| Charlies invaluable sheath-knife | 82 |

| The wreck of the Strathmore | 92 |

| Robert Aitkenhead Wilson, third-class passenger | 100 |

| Grande le, as painted by Charlie | 113 |

| The survivors hut | 116 |

| Second mate, Thomas Brown Peters | 132 |

| Landmarks of Grande le | 155 |

| Inside Penguin Cottage | 156 |

| Fetching water in penguin-skin pigs | 159 |

| Killing penguins | 161 |

| The survivors signalling to a passing ship | 177 |

| Souvenirs of Grande le | 196 |

| Nellie, wife of Captain Gifford | 200 |

| Captain Gifford of the Young Phoenix | 203 |

| Charlies wife, Georgiana | 215 |

| Charlie Wordsworth in the 1880s | 218 |

| Charlies design for Fannys gravestone | 227 |

| A fragment of Fannys gravestone | 228 |

The Crozet Islands, between Antarctica and Madagascar

Imagine one woman, forty-seven men and a three-year-old boy shipwrecked on a tiny sub-Antarctic island. For seven months they eat albatross and burn penguin skins for fuel, before a passing whaler picks them up.

The woman was my great-great-great-grandmother Fanny Wordsworth. She and her son, Charlie, my grandfathers grandfather, were migrating from Scotland to New Zealand when their ship struck a rock in the Roaring Forties, halfway between Antarctica and Madagascar.

I dont remember when I first heard the story. Probably my mother told me when I was still very small, perhaps five or six years old. Maybe we were in the car, driving home to Paekakariki from Hawkes Bay after visiting my grandparents.

Almost half the people on board drowned in the wreck, my mother would have said, perhaps looking in the rear-view mirror, flicking the indicator, pulling out to overtake the car in front. Mrs Wordsworth only survived because she wouldnt get into a lifeboat with the other women and children Charlie was far too old to count as a child and she didnt want to leave him.

So the little boy on the island wasnt her son?

No, he was no relation.

How old was Charlie?

Twenty-three. He was a grown-up already.

My mother keeps her eyes on the road.

The women and children in that lifeboat, she says, they all drowned.

Or perhaps it was in my grandparents dining room that I first heard of the shipwreck. In my memory it is a dark room, with light switches and door handles too high to reach. Theres a gigantic carved Victorian sideboard laden with flowered china, a silver teapot. We sit around the neatly set table: milk-jug, butter-knife, jam-spoon. At home, milk pours straight from the bottle and the same knife does for butter and jam. But things are different here: you must be polite and tidy; you must speak properly. My grandparents are old, with grey hair and withered, pouchy skin, false teeth and trembling hands. They wear hats out of doors, they smell of talcum powder and old-peoples clothes, they call me dear.

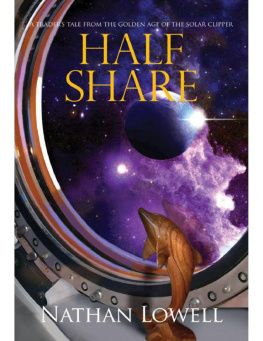

The whales tooth carved by Charlie Wordsworth and handed down to my grandfather

Here you are, dear, says Granddad, holding out a whales tooth covered in scrimshaw.

He tells me that Charlie did the carving, after the tooth was given to him by a sailor on the whaling ship that rescued the survivors.

Be careful, dear its very old.

The tooth is yellowy-white, almost as long as my five-year-old forearm. It is carved with a ship in full sail. Under the ship is a picture of an island. Above it are the American flag, the flag of the British Royal Navy, and the month and year of the rescue: JAN 1876.

The British flag is for the Strathmore, says Granddad. The ship that was wrecked. She was from Scotland. And the American flag is for the Young Phoenix, the American whaler that rescued them.

My grandfather was in his sixties when I was a child, which does not seem old to me now. At sixty-five my father wears T-shirts and sneakers, builds garden sheds, surfs the internet. But at sixty-five my grandfather was old a pipe-smoking, cufflink-wearing, handkerchief-carrying relic from a different time, the far-off olden days when everyone spoke properly and never said what they really thought.

As a child I wanted to visit the olden days. How would it feel to travel by sailing ship, wear strange and complicated clothes, live without plastic and electricity? But I knew Id have nothing to say to anyone who lived there the olden days were clearly full of old people. My shipwrecked great-great-great-grandmother and her son would be remote, neatly pressed beings to whom one must be polite.

Then, when I was a teenager, a relative gave my mother a typed transcript of two letters written by my ancestors on board the rescue ship, describing the wreck and their time on the island. The letters were meant for their family back home in Scotland and England, the relatives whod given them up for dead.

The transcript was typed in capitals, and was over twenty-five pages but I was enthralled. The voices of my forebears Fanny and Charlie Wordsworth spoke directly to me from the past. Some of the language was a little quaint, but the voices were vivid and real. They made jokes, talked about their sadness and fear, about their dreams, and the relief and joy of rescue. It was as if Granddad told me about a girl he had a crush on in primary school, as if the olden days had burst out of sepia restraint into full colour.

I read the letters, marvelled at them, talked about them, then put them away and forgot them till about four years ago, when this story of shipwreck began to acquire a new urgency for me. Several things happened around the same time: my mother got cancer, my marriage broke up, a woman whod been like a mother to me died, and I abandoned a novel Id spent years working on. In various ways I was confronted with failure, with losing what I wanted most love, a sense of belonging, success as a writer and with death.

My ancestors story spoke to me. They, too, must have wanted something badly no-one would risk that dangerous voyage without strong motivation. Setting sail for New Zealand, they fetched up on another island on the far side of the world, where they suffered, struggled and believed they would die. The story of their survival was also the story of mine if Charlie had died, I would not have been born. Of course, I knew the storys ending my very existence was the proof of Charlies rescue, at least but there was so much else I didnt know. What was it they wanted so badly? What were their lives on the island really like? What kept them going when they lost hope? Who were these people, my ancestors, and how had they changed by the time they were rescued?

Next page