ALSO BY A. S. BYATT

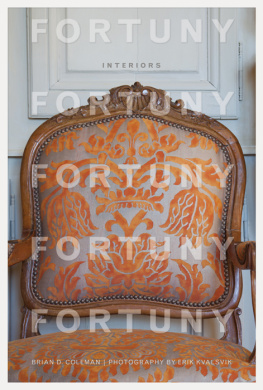

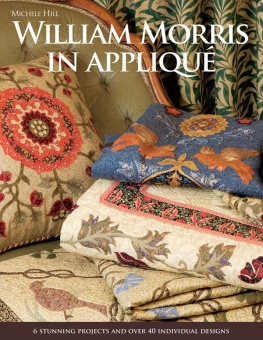

FORTUNY & MORRIS

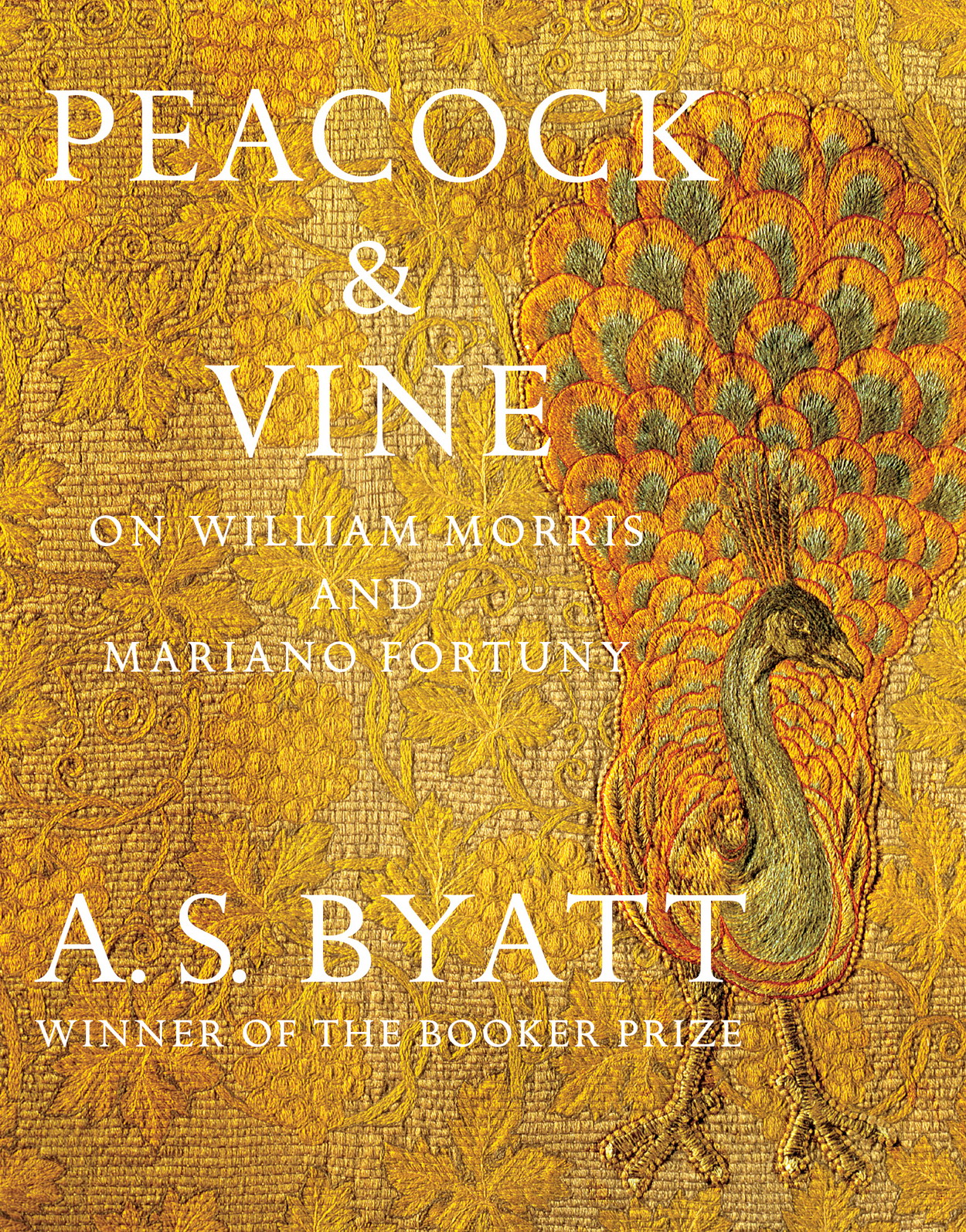

W e were in Venice in April and I was drunk on aquamarine light. It is an airy light, playing with the moving dark surfaces of the canals, shining on stone and marble, bringing both together in changing ways, always aquamarine. I found that an odd thing was happening to me. Every time I closed my eyes which I increasingly did deliberately I saw a very English green, a much more yellow green, composed of the light glittering on shaved lawns, and the dense green light in English woods, light vanishing into gnarled tree trunks, flickering on shadows on the layers of summer leaves. We were there to visit the civic museums, and I was very interested in the Palazzo Fortuny, the home of an artist of whom I had known almost nothing beyond the fact that he is the only living artist named by Proust in la recherche du temps perdu. I grow more and more interested in polymaths in the arts and I have always admired those whose lives and arts are indistinguishable from each other. And as I grow older I become more and more interested in craftsmen glass-blowers, potters, makers of textiles. My own ancestors were potters in the English pottery towns the Five Towns in Staffordshire.

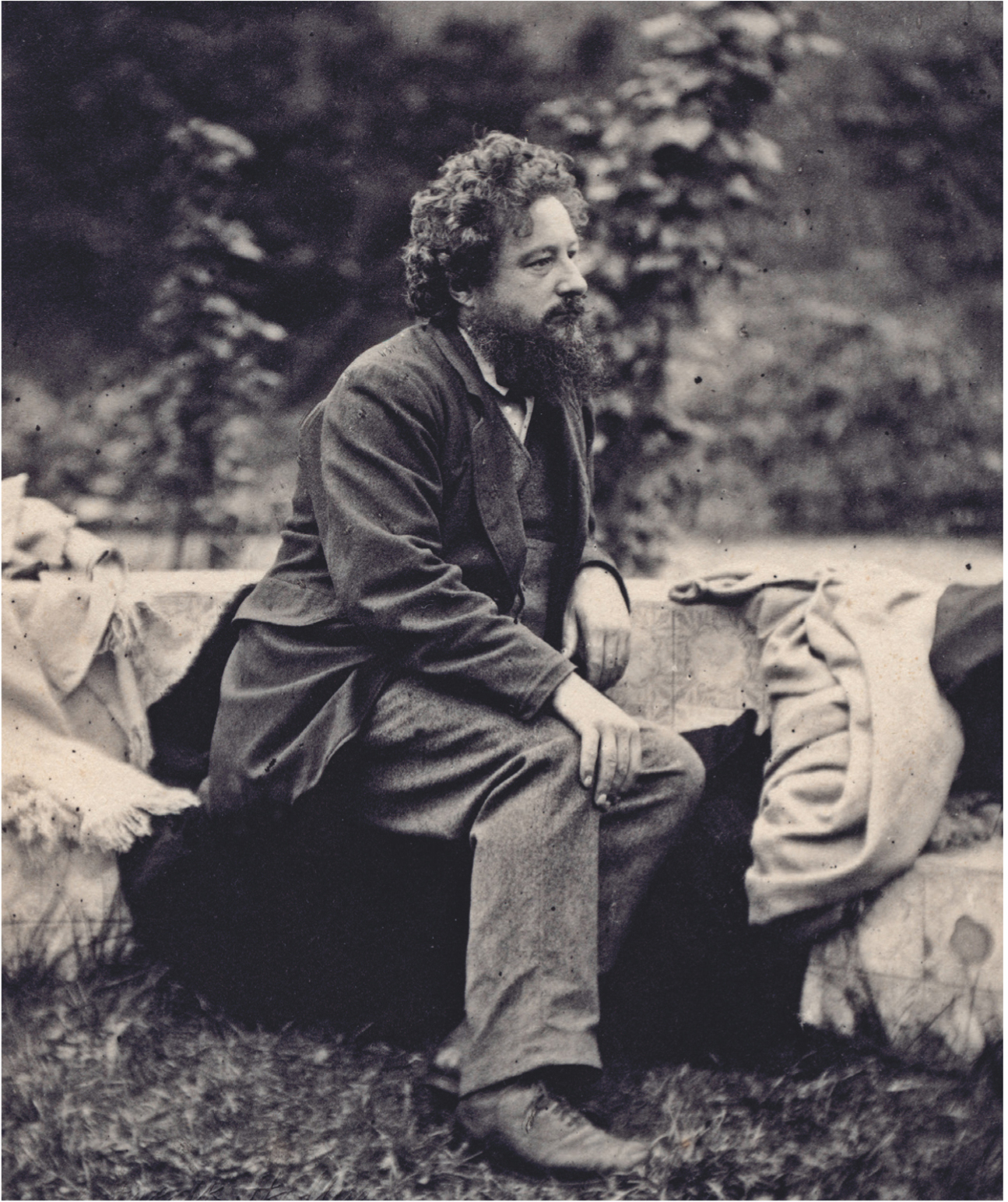

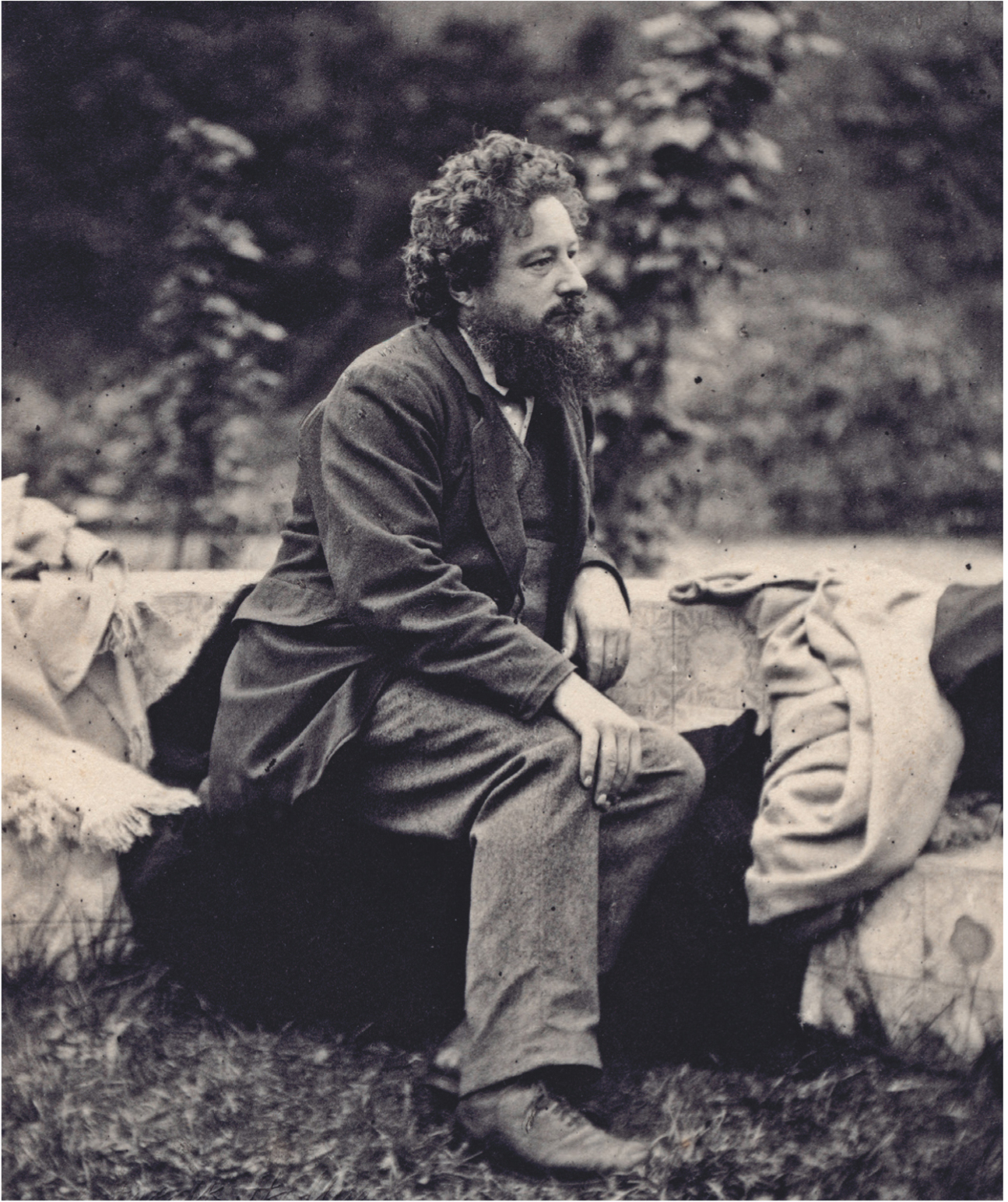

As I grow older, also, I have come to understand that my writing fiction and thinking starts with a moment of sudden realisation that two things I have been thinking about separately are parts of the same thought, the same work. I think, fancifully perhaps, that the excitement is the excitement of the neurones in the brain, pushing out synapses connecting the web of dendrites, two movements becoming one. Every time I thought about Fortuny in the aquamarine clarity, I found I was also thinking about the Englishman William Morris. I was using Morris, whom I did know, to understand Fortuny. I was using Fortuny to reimagine Morris. Aquamarine, gold green. English meadows, Venetian canals. When I came back to England and started thinking about Morris, visiting the museums that were the houses where he had lived and worked, I closed my eyes and found my head full of aquamarine light, water flowing in canals, the dark of the Palazzo Pesaro Orfei.

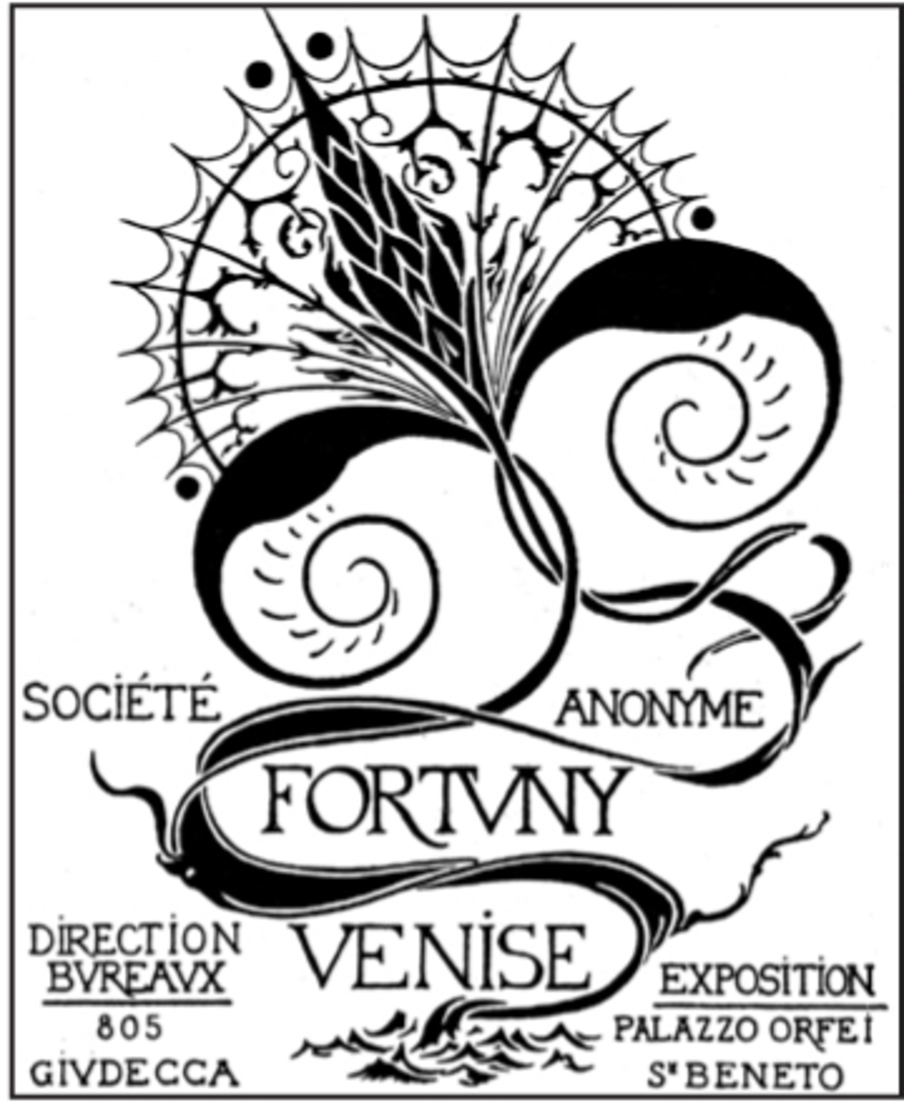

They were both men of genius and extraordinary energy. They created their own surroundings, changed the visual world around them, studied the forms of the past and made them parts of new forms. In many ways they were opposites. Morris was an English bourgeois whose father had made an unexpected fortune in tin mining. He became a convinced and passionate socialist. Fortuny came from an aristocratic Spanish family of painters and artists and lived in an elegant aristocratic world. Fortunys imaginative roots were Mediterranean North Africa, Crete and Delphos. Morris was obsessed by the North and the Nordic the Icelandic sagas, Iceland itself, the North Sea.

Mariano Fortuny was born in Granada in 1871. His father, Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, was a distinguished painter, and his mother, Cecilia de Madrazo, came also from a family of artists, architects and critics. Fortuny y Marsal died of malaria when he was only thirty-six years old his collections of pottery, armour, textiles and carpets, as well as his paintings and etchings were an essential part of Fortunys life and work. After his fathers death his mother moved to Paris, where her brother Raimundo was a celebrated portrait painter: the family moved in a world of artists and writers. In 1889 the family moved to Venice partly, at least, because Fortuny was allergic to horses, and suffered from asthma and hay fever. There they lived in the Palazzo Martinengo on the Grand Canal until Fortuny bought the Palazzo Pesaro Orfei in 1899. The move was partly because his mother did not approve of his companion, a French divorcee, Henriette Negrin, whom he met in Paris and who joined him in Venice in 1902, and whom he married in 1924.