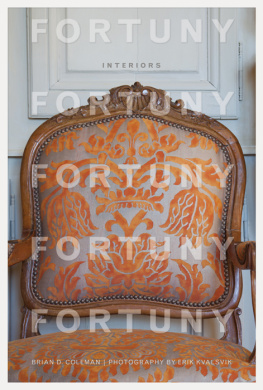

MARIANO FORTUNY, 18711949, BY GUILLERMO DE OSMA

Faithfully antique but markedly original, so Marcel Proust describes the fabrics and clothes of Mariano Fortuny, summarizing the essence of his work in this revealing phrase.

Proust was, as were a number of other writers, an admirer of Fortunys creations, but undoubtedly it was he who most brilliantly and intelligently analyzed Fortunys dresses and textiles with a clear-sightedness that left nothing to chance and little to poetic imagination. Proust offered the essential keys for understanding the unique and exceptional dimension of the artists work. By doing so, he makes Fortuny a leitmotivsmall, but essentialof his great novel, In Search of Lost Time.

With these five words Proust defined the foundation of Fortunys creations, not only as designer of fabrics and clothes, but of all of his vast work as painter, engraver, sculptor, photographer, set designer, lighting engineer, furniture and lamp designer, and inventor, the discoveries of whichfrom illumination systems to a boat propulsion systemhe zealously registered in the Paris Patent Office.

In such a convulsive and eclectic end of the century and, above all, particularly with the avant-garde period of the first half of the twentieth century, afflicted by isms that succeeded one another, anxious to break with the past in order to invent a modern present where art, design, and architecture provide a revolutionary repertoire for the new man, Fortuny remained on the edge of isms and polemics. Mariano worked untiringly in a totally personal way, shutting himself away from worldly noise, dedicated to his diverse and ambitious projects in this marvelous laboratory, which would be the Palazzo Pesaro degli Orfei, today the Museo Fortuny. Deaf to proclamations and manifestos of the international avant-garde, Fortuny did not have any problem with, or any fear of, looking at the past as a source of inspiration and ideas. Not in order to achieve something that would seem an imitation or a plagiarism, with that artificial and so theatrical aspect of copy, but in order to reinterpret the past into something modern and current. So modern and current that his fabrics, still produced today in the old Giudecca factory with its same artisanal methods on the machinery that he invented, decorate the most modern spaces and houses for the citizens of the twenty-first century. His dresses, in particular the famous Delphos of fine pleated silk, continue to be used by models, actresses, or society ladies as if they were novel and current creations, which would be unthinkable for the clothes of his contemporaries: Paul Poiret, Paquin, or Lanvin. On these same women, these would be seen as somewhat ridiculous, and completely out of fashion. Fortunys clothes have also inspired modern creators such as Mary McFadden or Issey Miyake with his Pleats Please series, as if it were an homage to the master.

It is also true that looking at the past was something natural for Mariano Fortuny. He was born in 1871 in Granada, a city full of vestiges and monuments of a very illustrious past where West and East, North and South, Europe and Arabic Africa flow together and converse. This double influence, especially Fortunys interest in the Arabic and eastern world, his other great source of inspiration, would be a constant in his work throughout his life.

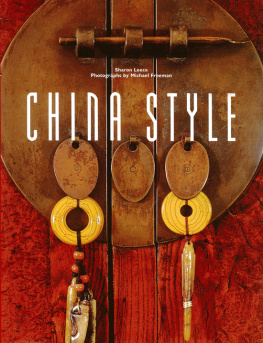

On the other hand, his own life made him an accomplice and participant in an illustrious past, which Fortuny did not disown and for which he would always have great respect and admiration, influenced by the fact of having lost his father, a brilliant and famous painterAmerican and European collectors paid fortunes for his paintingswhen he was only three years old. His father, whose palette and brushes, luminous and most exquisite paintings, and splendid engravings he kept, was also an important collector of weapons, ceramics, Arabic objects, and also fabrics. This collection of antique textiles with Renaissance damasks, medieval velvets, Chinese silks and brocades from the Orient was kept and enriched by his mother, Mrs. Cecilia de Madrazo, herself the daughter and niece of illustrious painters and architects. This collection would undoubtedly be the germ and inspiration of Fortunys extensive and highly varied textile work. Fortunys relation with the past was not superficial or anecdotal; it was a profound, almost biological relation, as if the past were a part of himself, which he understood and accepted naturally. It was not an imposed or academic past, but a living and revitalizing one. As someone who knows something well and appreciates it, Mariano did not want to imitate it without infusing it with new life. That is what Fortuny did, regenerating that past, using his resources and enormous capabilities well to create something modern, perfectly coherent with the world of his time and in the case of the fabrics and dresses, with the world of the twenty-first century.

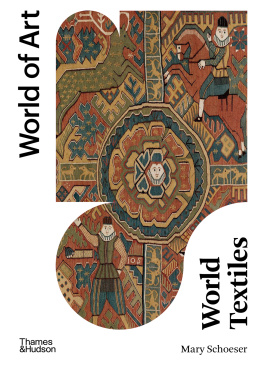

How did he give it new life? On the one hand, by new production techniques. All of his fabricsvelvets, silks, cottonsare stamped; it is the only technique which he used for applying the chosen motif onto the textile support. For Fortuny, it was essential to control all of the production process, and everythingexcept the fabric, which arrived rawwas first made in the workshops of the Palazzo Pesaro and later in the Giudecca factory. He produced the dyes, wood blocks, stencils, printing machinerywhich he patented with his other inventionsand finally, the culminating moment, the artisanal finish with the applications of gold and silver using diverse tools and the retouching by hand with brushes and sponges to obtain those so personal effects which immediately distinguish a Fortuny fabric. This irregular finish of profound richness is closely related to the painter in Fortuny. He considered himself foremost a painter, perhaps because it was his first training, and he would never cease painting. This would definitely mark his concept of fabric as if each piece, each meter were a painting and therefore always different and unrepeatable. His fabrics are profoundly personal, as Proust says referring to the clothes, to such an extent that they could be given a name.