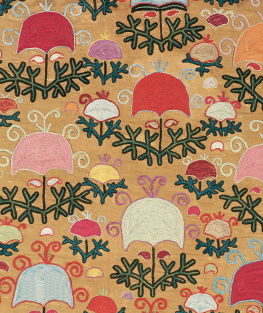

18th-century embroidered velvet Koran folder

To Terry E. McLean (19502016), who forgave my round-the-clock writing

About the Author

Mary Schoeser is a recognized authority on the history of textiles. She has advised organizations such as English Heritage, the National Trust, Liberty of London, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Her publications cover the full range of textile history, from the textile entries in Materials and Techniques in the Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Dictionary (2002) and monographs on textile artists such as Rozanne Hawksley (2009), to surveys of contemporary work in International Textile Design (1995) and its context in Textiles: The Art of Mankind (2012). Currently an honorary senior research fellow at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, she has served fifteen years as the Honorary President of the Textile Society (UK) and remains Patron of the Bernat Klein Foundation and the School of Textiles, Coggeshall.

Contents

A comparison between prehistoric and present-day textiles demonstrates the lack of logic in a linear history, which takes us from simple to complex, or from plain to patterned. Many of the materials, techniques and forms used in ancient times remain in use today, both as essential aspects of production in many regions of the world and as ingredients in textile arts. Such continuity makes textiles unique among all artifacts. The fact that their making often involves the creation of the ingredients unlike working with wood or stone makes them extremely complex and revealing of human ingenuity. It can be argued that as indicators of cultural mechanisms, textiles offer insights into the greatest range of developments, embracing not only technology, agriculture and trade, but also ritual, tribute, language, art and personal identity.

The relationship of textiles to writing is especially significant, not only for the cuneiform-like qualities of many patterns (preserved in a Hungarian term irsos, meaning written), but also for the parallels between ink on papyrus and pigment on bark cloth. There is, in fact, little difference between the two. Such connections are implied in many textile terms. For example, the Indian full-colour painted and printed kalamkari are so named from the Persian for pen, kalam; the wax for Indonesian batiks is delivered by a copper-bowled tulis, also meaning pen. The European term for hand-colouring of details on cloth is pencilling. The Islamic term tiraz, originally denoting embroideries, came to encompass all textiles within this culture that carried inscriptions. And the patterns woven into the silks of Madagascar are acknowledged as a language: the Malagasy vocabulary for writing and preparing the loom are synonymous, while the finest stripes are zanatsoratra, literally children of the writing, or vowels.[] The study of textiles is, in fact, a branch of palaeography, in which deciphering and dating reveals the stories encapsulated in cloth handwriting.

Being both functional and decorative, textiles can be read in many ways. This wallpocket of 171030 displays figures representing Faith, Hope and Charity, and the Four Cardinal Virtues as identified by Plato. It has significance for studies of classicism, Christianity, Western concepts of women, and the role of needlework in a young womans education. Made of plain silk taffeta, silk floss, silver and gilt thread and gold lace and braid, it also documents the fine materials then available in Engadine (Grisons canton, Switzerland), as well as the skills and taste of its maker.

With or without inscriptions, textiles convey all kinds of texts: allegiances are expressed, promises are made (as in todays bank notes, whose value is purely conceptual), memories are preserved, new ideas are proposed. Records were kept in quipu (khipu) a method of knotting string used by the Incas and other ancient Andean cultures to keep accounts and communicate information, the oldest of which is some 4,600 years old. Many anthropological and ethnographical studies of textiles aim at teaching us how to read these cloth languages anew. The plot is provided by the socially meaningful elements; the syntax is the construction, often only revealed by the application of archaeological and conservation analyses. Equally, the most creative textiles of today exploit a vocabulary of fibres, dyes and techniques. Textiles can be prose or poetry, instructive or the most demanding of texts. The ways in which they are used and reused add more layers of meaning, all significant indicators of sensitivities that can be traced back to the Stone Age.

Recent scientific dating methods have located the DNA distinction between clothing lice and body lice, which can be dated to some 190,000 years ago, long predating the so-called cognitive revolution, a period during which hominids developed language, theorized as a replacement for grooming. Yet textiles intersect with both, being expressive as well as comforting, a fact not yet enfolded in studies of human development. Cognitive neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists confirm that our brains devote more study time to complex surfaces, decorative patterns, curved shapes, three-dimensional features and multiple colours, essentially seeking to find the pattern and spot the difference, the essence of all intellectual enquiry. The action of making, as much as observation of the material result, encapsulates visual and theoretical analysis and learning, as well as documenting and sharing of ideas as much as textiles themselves. Might one now propose that we started stitching and making baskets and got smart, rather than the other way around?

Taking a lead from textiles also engenders a more balanced understanding of the indigenous cultures that never developed the use of bronze and iron (as in Australia), developed iron use alone and comparatively late (as in Africa in about 800 BC), or developed the use of copper followed rapidly by iron (as in the Americas in about AD 100). As the climate warmed at the end of the last Ice Age (c. 7000 BC), the loss of abundant vegetation in certain areas forced communities to redirect observational and manipulatory skills in order to settle, allowing the control and preservation of food supplies. Yet these skills were already highly developed through centuries of experience with textile materials and techniques, and their contribution to agriculture and animal husbandry can be readily deduced, not merely in the use of cordage and bands for ploughs and reins, but, more significantly, in the way such concepts were expressed: haft, for example, means not only to bind and handle, but also to habituate animals to a particular pasture, resulting in hefted flocks. Scholars now confirm that fibre, fur and feather production and their use for clothing and shelter was developed in response to global warming: agriculture was initiated for textiles rather than food. Considering all this, could not the same skills have contributed to the development of metallurgy? Certainly gold was manipulated into threads at least by the 11th century BC; metallurgy and textile techniques later become closely related through joint applications in machine-building and as a result of the lead taken in organic chemistry by first dye, and then fibre, sciences.

Next page