To the intrepid travelers who braved the khans and the Bolsheviks; trekked across frozen steppes; traversed the Kyzylkum and Karakum Deserts; crossed the Pamirs, the Roof of the World; and returned home to write about it.

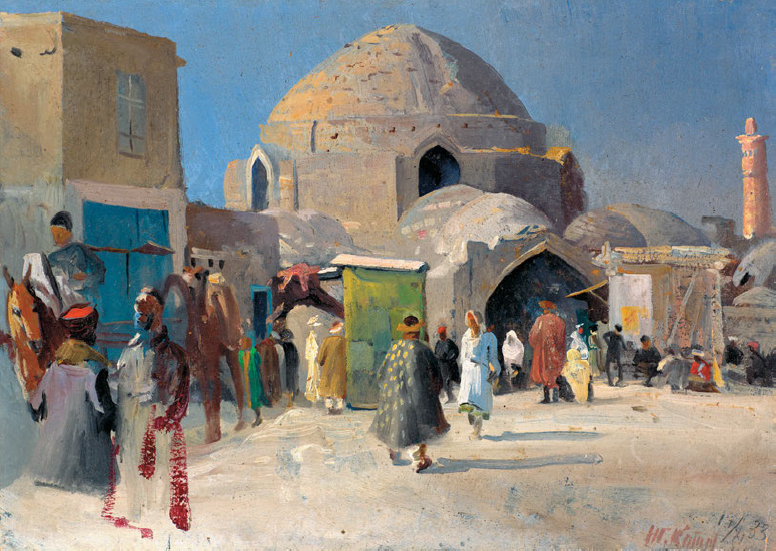

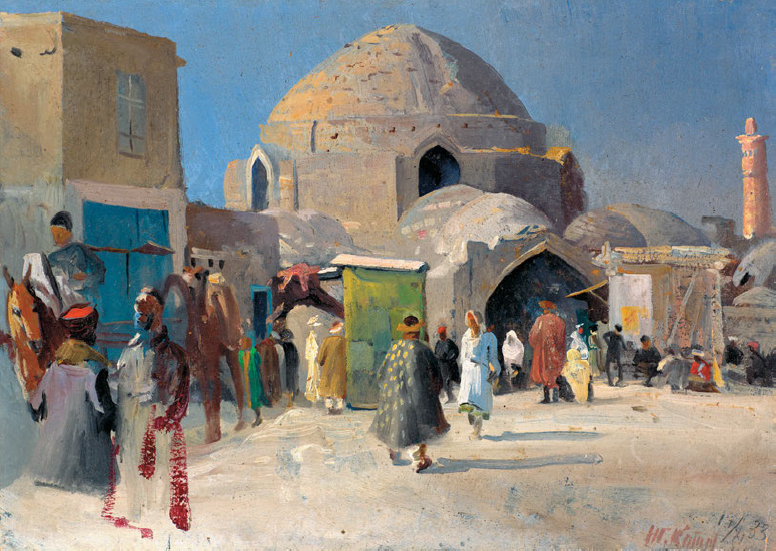

1933. Oil on board, 10 x 14.5". Authors collection.

The Taqi-Zargaron (jewelers market) was built in the 16th century, and today the mud-brick vaulted dome still houses merchants in mysterious recesses where rubies and emeralds and Circassian slaves once changed hands for fabulous prices. On the far right of the painting is the Kalyan Minaret. One hundred fifty-eight feet high, it was the tallest freestanding building in the world at the time it was built in 1127. Kotov was an acclaimed Russian artist who spent a considerable time in Central Asia painting scenes of everyday life.

for full description

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Of a sudden one hears the muted sounds of bells far away. It is strange music, it creates an impression that is magical. It makes one sleepy. The sound gets more and more precise, finally it is very close. Like huge black ghosts, the camels appear out of the darkness; slowly, majestically, with dignity they move across the desert sands. Sven Hedin, letter to his family

For the past decade, I have traveled extensively through the Central Asia of the khans, the tsars, the Bolsheviks, and the Soviets. My guides spanned eight centuries. They were English, Russian, American, Swedish, Danish, Austrian, Swiss, Spanish, Italian, Hungarian, and Moroccan. They were explorers, adventurers, geologists, ethnographers, clergymen, merchants, journalists, diplomats, counter-revolutionaries, and spies. Indomitable travelers all, they endured brutal hardships and returned home to tell about them. These men and women are gone now, but their experiences and observations remain vividly alive in the books they left behind. Some had political and/or self-serving agendas, in particular those Russians and British engaged in the struggle for control over Central Asia in what came to be known as the Great Game. Some were influenced by their ideological sympathies, for example pro-tsarist or pro-Bolshevik. But most took it upon themselves to record what they saw as accurately as they could, albeit through a personal lens. These are the people who have shaped my impressions of the Central Asia that was.

As I worked on this book, a phrase kept cropping up in my mind: Nothing is as it seems. At times the process of creating Silk and Cotton was like an archaeological dig. Exciting finds, both textiles and tidbits of information, were uncovered, only to have other discoveries cast doubts. One experts opinion contradicted anothers. Like mirages on the shifting sands of the Takla Makan Desert, facts could be elusive. Central Asia, or Turkestan as it was formerly known, is a jigsaw puzzle with a million tiny, scattered pieces. Ive gathered some of those pieces in this book and fitted them together into a small part of the whole, offering the reader a glimpse into an enigmatic place and its people. As that astute Hungarian Orientalist and traveler Arminius Vmbry wrote in the preface to his book Sketches of Central Asia (1868), The slightest notice of a country so little known to us as Turkestan, which political questions will soon bring into the front of passing questions, will always have its uses.

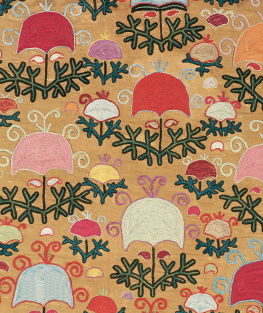

Central Asian people lived their daily lives surrounded by textiles, most of their own making. Textiles defined practically every aspect of their traditional way of life, beginning with a young girls dowry, through marriage, childbirth, old age, and death. There were suzanis for the marriage bed; niche covers; prayer mats; patchwork bedding quilts; camel trappings for a bridal procession; bags to hold tea, scissors, and mirrors; crib covers; lovingly embroidered childrens hats; and robes of every color and pattern. Having spent many years as a textile designer, I was first attracted to the unusual patterns on the Russian-export cottons that lined many ikat robes. It was next to impossible to find just the cloth itself, so I began buying old robes simply for their printed linings. The collection grew until the time came to open the robes and give the long-hidden linings their due. Russian Textiles: Printed Cloth for the Bazaars of Central Asia was published by Abrams in 2007. As I became more immersed in the rich and varied textile culture of this region, it became impossible to focus only on liningsthey were part of a much wider worldand so my collection expanded, and this book became the companion to Russian Textiles. With a few exceptions, the textiles illustrated in Silk and Cotton are drawn from my collection and, as such, reflect my personal taste. Rugs are not included as they are a world unto themselves; nor are other woolen items, such as tent bands and woven storage bags.

When writing about the broad spectrum of Central Asian textiles, one must invariably face the issue of transliteration. While Turkic and Persian dialects as well as Russian are still widely used, more than a century of Russian control has added further layers to the complexity. In many areas, the written language went from Arabic (prior to 1928) to Latin (192840) to Cyrillic (194091) and back to Latin (post independence). Spellings, translations, and pronunciations continue to evolve. Ascribing a name to a particular item is daunting. Take, for example, a hat: Not only does each broad ethnic group have their own generic word for hat, each regional area or tribal subgroup has a term for its distinct style of hat, and as these styles vary, further descriptive terms come into playall with multiple spellings. Because geographical names changed throughout history (depending on who was in power at the time) and spellings varied widely, I chose what appeared to be the most commonly used term prior to Central Asian independence in 1991.

I think of this book as a Central Asian album that introduces the reader to a broad range of silk and cotton textiles as well as to the people who made them. This is indeed such a vast and complex region that to do much more than introduce is not possible within the constraint of three hundred pages. To try and assign an attribution to every textile as to ethnic group, date, and place of origin is perhaps overly ambitiousactually, probably impossible. However, with pieces that were problematic, I chose to risk erring on the side of an educated opinion rather than offer no opinion at all. Whenever possible, I sought the input of other people well versed in Central Asian textiles. I also felt it important to put the textiles within their cultural-historical context. Period photographs by Russian photographers Max Penson and Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii; Western travelers such as Annette Meakin, Stephen Graham, and Edward Murray; explorer Sven Hedin; and photojournalists Maynard Owen Williams and John McCutcheon, among others, all give a sense of time and place. Each textile has its own integrity, and Don Tuttles photographs do them justice. Some examples are particularly fine and showy, such as the early suzanis, but most are ordinary pieces made for everyday use. These are the textiles that were, and sometimes still are, part of the lives of the people of Central Asia.

Next page