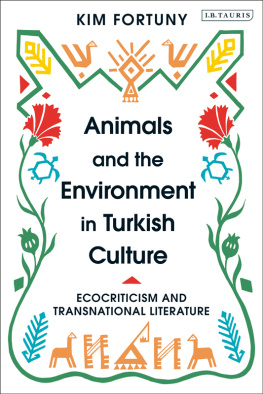

Animals and the Environment

in Turkish Culture

Animals and the Environment

in Turkish Culture

Ecocriticism and Transnational Literature

Kim Fortuny

To my dear Mother, Darlene Fortuny

And in memory of Electric Jim, my Dad.

This book has traveled so much distance that it is easy to forget all the people and places that have contributed to its inception and production. I have a number of families to acknowledge, the first being my academic family at Boazii University, Istanbul. Foremost, I would like to thank the extraordinary research assistants who made this book possible, namely, Arif Camolu and pek Kotan. Their consistent enthusiasm, diligence, and professionalism have been a gift to me. Other graduate assistants whose contributions I appreciate include Lamia Kabal and Aysun Kan and, in the final stages, student assistant Bura Bakan. I have been very fortunate to find a home away from home in my professional life. My mentors and colleagues in the Department of Western Languages and Literatures at Boazii University are also some of my closest friends and working side by side with them through the years has been a privilege and a pleasure. Our remarkable students are also a source of energy and hope, and I appreciate daily the work we do together. Many anonymous peer reviewers offered excellent suggestions that improved the text and I send my gratitude out to them.

My family of friends who have helped sustain me through the writing process is a large one. Special thanks to Emine Fiek and Baak Demirhan for the daily nuts and bolts of living. Elif nl, Ethan Guagliardo, and Leila Braverman for every other day. Thanks to my sister Glen Gler and brother Zafer Sar. Friends distant but dear include Meg Russett, Ingrid, and Gerard Philippon, Rhonda Roth and the Oxbow Park yoga people. And all the Altman Rd. people, Paula and Herb, Joan and Kerry, Karil and Scott. Special thanks to Hakan Yeildere.

Lastly, I would first like to thank my superior mother for doing what she does most naturally, supporting and nurturing those around her. She has been a constant source of love and friendship for me and I dedicate the book to her. Our father Jim Fortuny would have liked this book and recognized himself as the early inspiration for all things wild. I thank him profoundly for that. I miss you. I would also like to thank my siblings Jill, Ralph, and Guy for being my people and also my niece Isabelle and all the other offspring who make summers in Oregon a beautiful thing.

Three of these chapters originally appeared as articles, in slightly different form, in the following publications: Herman Melvilles Near East Journal and Ahmet Hamdi Tanpnars Five Cities: Affinities of Culture, Nature, and Islamic Mysticism in Istanbul. Nineteenth-Century Contexts. 37.2 (2015): 127145; Natures Place in Political Romanticism: Selected Poems by Nzm Hikmet appeared as Nazim Hikmets Ecopoetics and the Gezi Park Protests. Middle Eastern Literatures. 19.2 (2016): 162184; Islam, Westernization and Post-Humanist Place: The Case of the Istanbul Street Dog. ISLE (Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment). 21.2 (2014): 271297.

The research and writing of four chapters were made possible through grants provided by BAP projects at Boazii University, Istanbul, Turkey: : Ecopoetics, Dead Metaphors, and Bird Migration: The Bosporus Passage of the European White Stork (No 12940, P. Kodu 17BO4P4).

Although a Pacific Northwest American with roots in the foothills of the Oregon Cascade Mountains and Willamette River Valley, I have spent a good part of my adult life, and all of my professional life, in Istanbul, a complex and crowded old world metropolis. When one thinks of Istanbul one does not think of nature per se. But it is perhaps this assumption that has fed my desire to think through questions of post-humanism the relevance of Romantic poetics to contemporary green movements, the place of feral animals in cities, the political relevance of public green space, and other similar topics that occupy my writing here. To move back and forth between contrastive environments, one relatively rural to one emphatically urban has been, and continues to be, a constant exercise in revision and adaptation. We work with what we have at hand: Write what you know, Hemingway frankly advised. When one is lucky, life can deal us a rich if sometimes disjunctive range of experience. And with experience comes something akin to knowledge, or so one hopes.

This book reflects this sometimes uneasy movement between landscapes and cityscapes. It also attempts to negotiate through inclusion the various voices that make up the books polyphonic world, some Turkish, some North American, some literary, some theoretical. While the primary focuses of the book are selected environments, animals, and literary texts in Turkey, my own background in American literature circulates throughout these discussions. Nature, of course, does not recognize national borders or identity, though biotic life adjusts or reacts to walls erected by humans to contain it or keep it out. In this spirit, the various landscapes that follow come together with diverse cultural or intercultural references and literary and non-literary texts under the auspices of an impartial natural world. They also come together in response to the conviction that work that responds to environmental pressures on the world we live in must engage the local, wherever that may be, as well as the global. If were lucky, we have access to both.

The transnational worldview at the center of this book has a personal textual history. In a previous book, American Writers in Istanbul (Syracuse UP 2010), I traced my own bicultural experience in the writing of canonical writers such as Herman Melville, Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Paul Bowles, Nelson Algren, and James Baldwin. Most of these writers only stopped by long enough to fall in love or disillusionment before moving on. Most of these writers only stopped by long enough to fall in love or disillusionment before moving on, all except James Baldwin who made Istanbul one of his alternative homes throughout the 1960s. It was Melville, however, who would prove to be the bridge to the focus of inquiry that occupies the present text: nature. In my chapter on his Near East Journal entries dedicated to his visit to Istanbul in 1856, I had argued that his record of the city suggests that there is much about Istanbul that reflects a lawlessness or detachment in the relationship between man and nature, an important theme in Moby Dick. While nature is not empathetic in Istanbul, just as the whale is disinterested, man and his monuments nevertheless seem to co-exist stoically within a natural urban wilderness. Melville suggests, I argued, that nature and human culture in Istanbul tend to their own detached, yet synchronic, rhythms. These assessments were based on close readings of the journal notes and my own readiness to read Melvilles focus on cemeteries and mosques as indicative of a larger preoccupation with the interconnectedness of cultural monuments and nature and something ineffable, call it spirit, that penetrates both.

One day I received an unpublished English translation of a chapter on Istanbul by the early twentieth-century Turkish writer Ahmet Hamdi Tanpnar from his book-length work of non-fiction Be ehir (Five Cities). The translator was Ruth Christie and the chapter has since been published in Texas Studies in Literature and Language (2012). Tanpnar, whose fastidious, lyrical prose was and continues to be too difficult for me to read with ease in Turkish, entered my life like a beloved great uncle. All that I had been trying to sort out in the Melville chapter of my book suddenly had a better, wiser precedent. This is what Tanpnar had to say about trees:

Next page