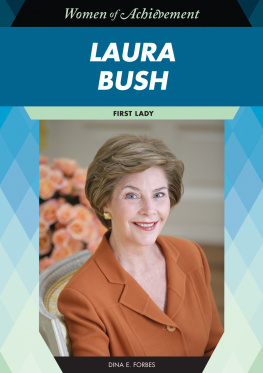

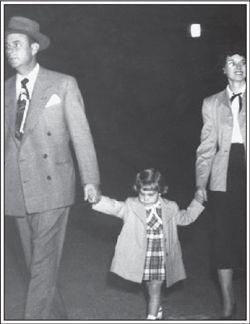

My parents and me at the Texas State Fair.Spoken from the Heart Laura Bush

My parents and me at the Texas State Fair.Spoken from the Heart Laura Bush

SCRIBNER

New York London Toronto Sydney

SCRIBNER

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 www.SimonandSchuster.com Copyright (c) 2010 by Laura Bush All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020. First Scribner hardcover edition May 2010 SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc. used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work. For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com. Manufactured in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN

978-1-4391-5520-2 ISBN 978-1-4391-6034-3 (ebook)

For the joys of my heart,my husband, George;my daughters,Barbara and Jenna;my mother;and the memory of my dad.CONTENTSThrough the Nursery GlassDreams and DustTraveling LightOne Hundred and Thirty-two RoomsGoodness in the Land of the Living"Grand Mama Laura""I Told You I Would Come"Prairie Chapel MorningsAcknowledgmentsBibliographyIndex Through the Nursery GlassMy first birthday.

Through the Nursery GlassMy first birthday. What I remember is the glass. It was a big, solid pane, much bigger than our little rectangles at home, which sat perched one on top of the other. I can still picture that window and the way it seemed to float on the wall without any curtains or wood. Beyond the glass was the nursery, where they kept the babies.

I don't remember looking at a baby. In my mind, there is only the window, although my brother, John Edward Welch, is lying on the other side of the glass. It is June of 1949 in Midland, Texas, and I am two and a half years old. I do not remember if I stood on my tiptoes or if my father held me, smelling as he often did of strong coffee and unfiltered cigarettes. He would have dressed me himself that morning in a pretty cotton dress that my grandmother had made. She made almost all of my clothes, choosing her own cute patterns and fabrics, sewing them on her old treadle Singer sewing machine, the needle clacking up and down as she pumped the pedal with her foot.

Whatever scraps her scissors had left behind she would take and carefully turn into matching doll dresses. Then she would bundle them up, a few at a time, and mail them from El Paso to Midland. Later, when the ranchers' daughters and the oilmen's girls were riding with their mothers on the train into Dallas to buy their first school dresses, pink or ruffled, with white lace or pert satin bows, at Neiman Marcus or Young Ages, my grandmother was still posting her cotton creations for me on the mail train from El Paso. Although the Western Clinic was less than ten blocks from our little house on Estes Avenue, with its hint of a front porch and postage stamp yard, where the grass was continually battling drought and dust, we would have driven there, in my father's Ford. I was born on November 4, 1946, at the same little Western Clinic, a one-story building, concrete and cinder block, with rows of decorative thick block glass and thin windows. It was built over a decade earlier, in the lean years of the 1930s, when Midland was a town of some 9,000 people.

But by 1949, Midland was closing in on 22,000 people, and Western Clinic was still all there was. It had a scant thirty-six beds. Patients were simply patched up and moved on. There was a long waiting list for surgeries. The clinic could not afford to let anyone dawdle; as soon as they were able, perhaps even before, patients went home. Dr.

Britt, who ran the clinic, had been brought in to practice in Midland by the oil companies. He birthed babies, treated sick toddlers, set broken bones, and watched hearts fail. Western Clinic didn't have a blood bank until 1949. Its Xrays were packed up and sent by commercial bus to a radiologist in Fort Worth. The drive alone was more than six hours. And once that bus had left, Dr.

Britt could only wait until the next one was ready to depart from the depot. The city also kept a small Cessna-style plane parked alongside the grassy landing strip at the airport to fly patients in and out and to ferry pathology samples over to a doctor in San Angelo. When the brand-new, $1.4 million Midland Memorial Hospital opened, in 1950, the X-rays were still bussed and the surgery samples still flown. But this was 1949. There was barely an obstetrical or surgical unit inside Western Clinic by the end of that year. My parents would have known this.

My father's brother, Mark, was a doctor in Dallas. But we lived in Midland, and there was no way to move a fragile baby, born unexpectedly two months too soon. My father had always wanted a son. In February of 1944, when he and my mother had been married for a few weeks, he wrote her a letter from a training base in North Carolina. A thirty-one-year-old GI, he was waiting there to be shipped to England. On thin airmail paper, in his tall, narrow, and meticulous script, Harold Welch wrote to his new bride, Jenna, who was not yet twenty-five, "Honey, what do you want, a little boy or a little girl? What you want, I want, it makes no difference to me, but I'd kind of like to have a little boy, would you?" I see them now in an old photograph, my grandfather Hal Hawkins, looking hot, uncomfortable, and a bit dour in his jacket and tie, his belly straining against the buttons of his white shirt, his hair refusing to stay slicked back and instead slipping down over his forehead.

On the other side of the picture is my father, a head taller, hair neatly cropped, in his dress uniform, grinning and handsome, "so handsome," as my mother says, "with the most beautiful blue eyes." And between them is my mother, her arms through the arms of the men beside her, her head flung back in laughter, her whole face alive with a look of pure joy. Harold and Jenna waited two years for each other. My father shipped home in January of 1946. Two years beyond their vows, they were still newlyweds. My mother was an only child, and when I was growing up, she would say with a wink in her quick, witty West Texas way that she would have been "insulted" if her parents had had more children. But that is only part of the story, the way when you dig down through the dry West Texas flatlands you discover the fossilized remnants of shells and underwater life, what remains of the ancient, vanished Permian sea.

Only when I was much older did I learn that my grandmother had lost her own babies, two babies, my mother thinks, both of whom were born too soon and died. But she never truly knew because no one spoke of it. You might talk about the wind and the weather, but troubles you swallowed deep down inside. My mother's own pregnancy with me had been hard. She did as the doctors told her and spent most of it in bed. This time she had gone to bed too, but the baby still came early, gasping, with no high-tech incubator to warm him, no pediatric IV line to put in his tiny arm, nothing but swaddling blankets and a few sips of formula from a glass bottle or given with an eyedropper, the way one feeds an injured baby bird.

Next page

My parents and me at the Texas State Fair.Spoken from the Heart Laura Bush

My parents and me at the Texas State Fair.Spoken from the Heart Laura Bush Through the Nursery GlassMy first birthday. What I remember is the glass. It was a big, solid pane, much bigger than our little rectangles at home, which sat perched one on top of the other. I can still picture that window and the way it seemed to float on the wall without any curtains or wood. Beyond the glass was the nursery, where they kept the babies.

Through the Nursery GlassMy first birthday. What I remember is the glass. It was a big, solid pane, much bigger than our little rectangles at home, which sat perched one on top of the other. I can still picture that window and the way it seemed to float on the wall without any curtains or wood. Beyond the glass was the nursery, where they kept the babies.