JOHN MILTON

Life, Work, and Thought

JOHN MILTON

Life, Work, and Thought

GORDON CAMPBELL

THOMAS N. CORNS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Gordon Campbell, Thomas N. Corns 2008

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Clays Ltd., St Ives plc

ISBN 9780199289844

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Mary and Pat, our espoused saints

Illustrations

A Note on Dates

THE dates used in this biography take account of two peculiarities in the calendar of seventeenth-century England. First, the Julian calendar in use in England and in some Protestant countries on the continent was ten days behind the Gregorian calendar in use in Catholic countries; Shakespeare and Cervantes are sometimes said to have died on the same day (23 April 1623), but in fact Cervantes died ten days before Shakespeare, because Spain had adopted the Gregorian calendar. The Julian Calendar is known to historians as Old Style (OS) and the Gregorian, which was not adopted in Britain until 1752, as New Style (NS). In the chapter on Italy we use split dates, so Milton is said to have read a poem to the Svogliati on 6/16 September 1638, which means that it was 6 September in England and 16 September in Italy.

The second discrepancy concerns the start of the new year. In Scotland and on the continent the new year was generally reckoned to start on 1 January, and in England this convention was used for dates on printed title pages. In English documents written by hand (including dates written on books), however, the year is deemed to start on 25 March, the Feast of the Annunciation. Miltons Tenure of Kings and Magistrates was published on or about 13 February 1649, and has that year on its title page; a presentation copy now in Exeter Cathedral Library is dated (by hand) February 1648. Some scholars split the dates (13 February 1648/49), but we have chosen the simpler alternative of using the modern convention of dating from 1 January, so we would write 13 February 1648/49 as 13 February 1649.

Seventeenth-century documents are also dated by a range of alternative means. Latin documents, for example, are sometimes dated by the Roman system of counting backwards from the three divisions of the month (calends, nones, and ides) rather than by counting forwards in ordinal numbers from the beginning of the month. State papers are often dated by regnal year, except during the years 1649 to 1660. Legal proceedings are dated by reference to the law terms, but legal documents, like ecclesiastical documents, are sometimes dated by saints days and festivals. In all such cases, we have silently given the date by modern conventions.

Finally, Milton dated ten of his poems by his age, using the formula anno aetatis (in the year of [his] age), but that formula is ambiguous: anno aetatis 17, for example, might mean that Milton was in his seventeenth year, but it usually seems to mean that he was 17. One of his Latin elegies (number 7), however, is dated anno aetatis undevigesimo (at the age of 19), and in this instance the use of a Latin ordinal number is probably meant to be taken literally, and the phrase therefore means in his nineteenth year rather than at the age of 19. In cases of doubt, we discuss the problem rather than bury it.

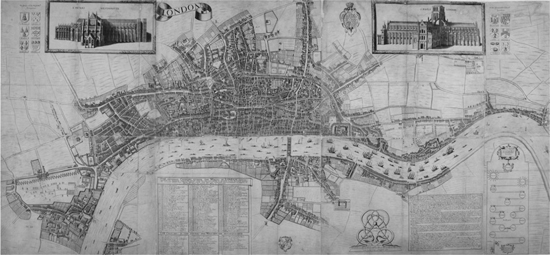

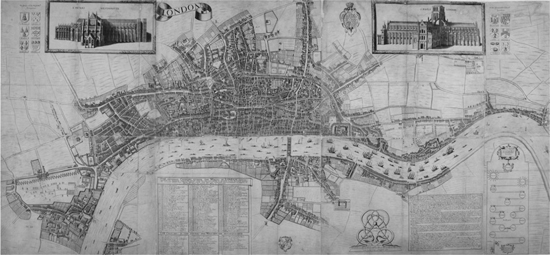

Map 1. William Faithorne, An Exact Delineation of the Cities of London and Westminster and the Suburbs thereof, together with the Burrough of Southwark (London, 1658).

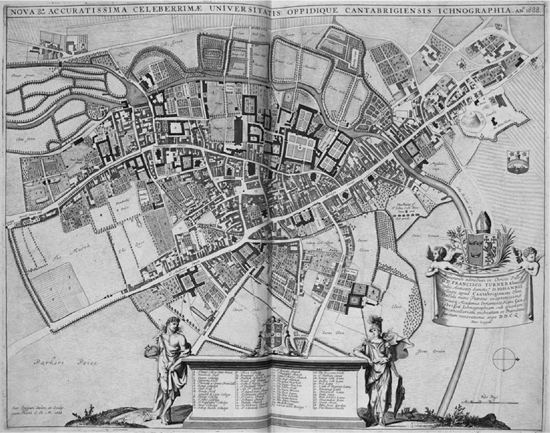

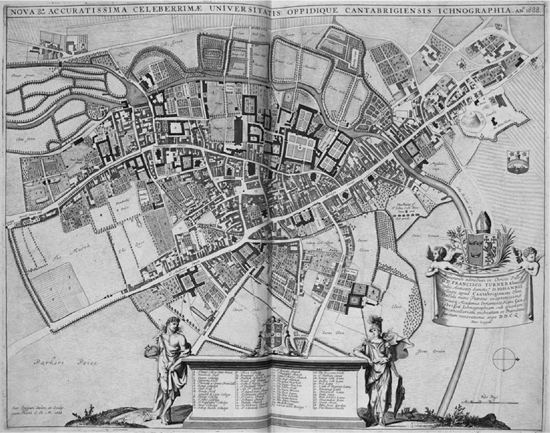

Map 2. David Loggan, Cantabrigia illustrata, sive, Omnium celeberrimae istius universitatis collegiorum, aularum, bibliothecae academicae, scholarum publicarum, sacelli coll. regalis (Cambridge, 1690).

Introduction

WRITING a biography of John Milton seems seductively easy, for two powerful reasons. First, much of the necessary information appears to be readily available. In the closing decades of the seventeenth century five lives were written by people who knew Milton or could draw information from others who did. Edward Phillips prepared an account of his uncles life for inclusion in an edition of Miltons state papers published in 1694. The freethinker and philosopher John Toland composed a life for his collected edition of Milton, so confirming the process whereby Milton was appropriated to the Whig cause.

The earlier lives have the authority of personal acquaintance for certain periods of Miltons life. The work of Wood and Toland is largely derivative, though Toland has some information not otherwise captured. A later life, by Jonathan Richardson (London, 1734) picks up a few anecdotes that others have missed.

Secondly, Miltons work does seem readily explicable in terms of his life: puritan son of puritan father, educated by puritans, writing on puritan themes against puritan enemies until the failure of a puritan revolution requires him to redirect those energies into the definitive puritan poem. Find and replace puritan with revolutionary or radical or progressive to taste.

Of course, the issues are not that simple. The early lives probably owe too much to Miltons prose writings, which in turn were shaped to meet the challenges of the fierce polemical exchanges in which he was engaged, and to the carefully crafted demonstrations of self-representation which occur frequently his poetry. The most useful and most influential for later biographers, those of Skinner and Phillips, are partisan apologias in defence of a good friend and a nurturing uncle, and they are designed to respond to the sorts of attack Miltons life and reputation had attracted. The documents which make up the life records require careful interpretation, which teases out their significance in their own age; placing them in their proper context sharply changes their meaning for the biographer. Perhaps the accounts that require the greatest measure of detachment are those in which Milton describes his own life (as in the

Next page