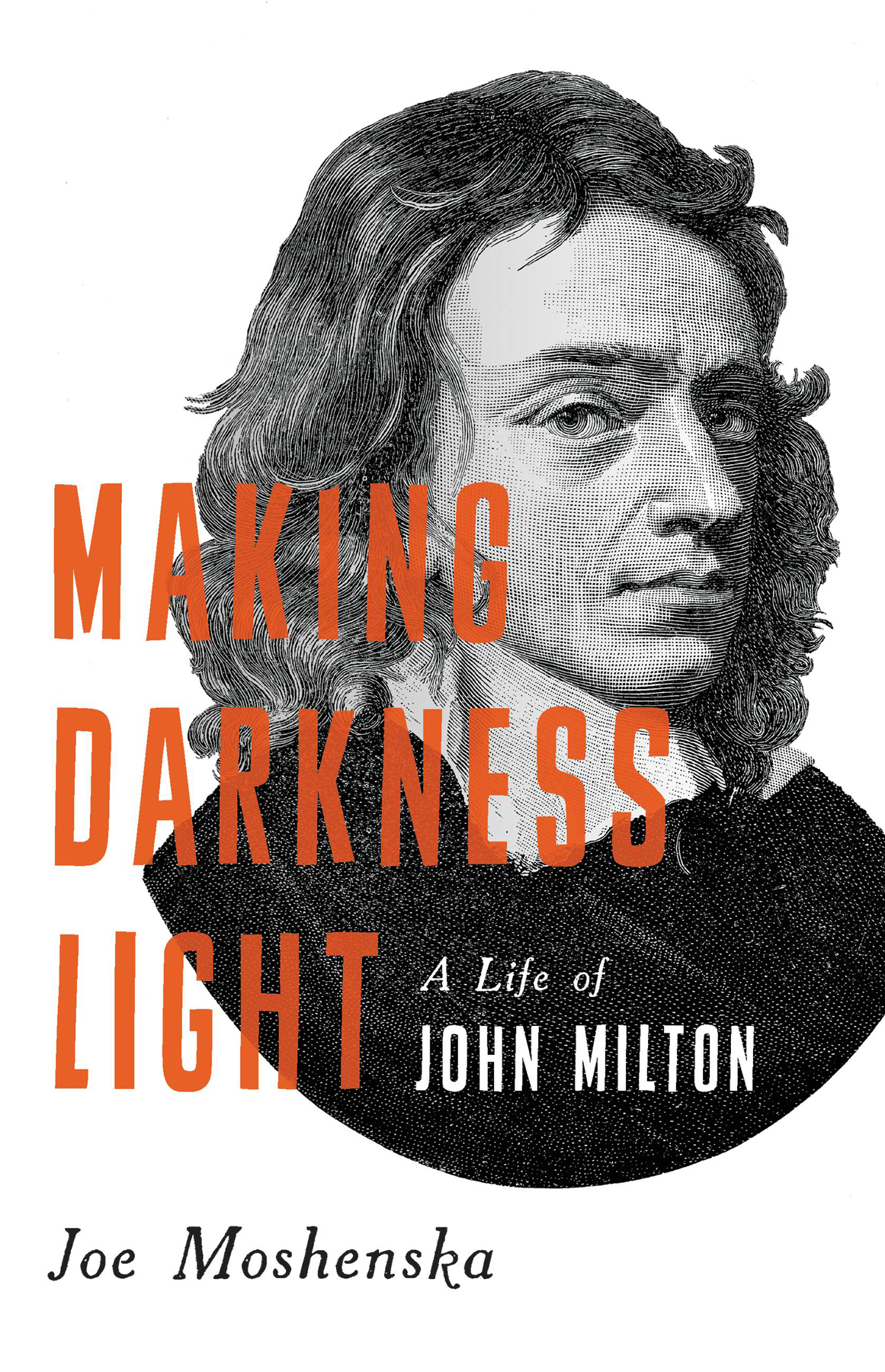

Photo credit: Rosa Andjar

Joe Moshenska is professor of English at the University of Oxford, where he teaches early modern literature. He is a BBC New Generation Thinker and his essays and reviews have appeared in the Times Literary Supplement , the White Review , the Financial Times , and the Observer . He received his PhD from Princeton and lives in Oxford, UK.

Feeling Pleasures: The Sense of Touch in Renaissance England

A Stain in the Blood: The Remarkable Voyage of Sir Kenelm Digby

Iconoclasm as Childs Play

Copyright 2021 by Joe Moshenska

Cover design by Chin-Yee Lai

Cover image Look and Learn / Bridgeman Images

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: December 2021

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Basic Books London, an imprint of John Murray Press, an Hachette UK company

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call () - 6591 .

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Typeset in Janson Text by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021943268

ISBNs: 9781541620681 (hardcover), 9781541620698 (ebook)

E3-20211027-JV-NF-ORI

For Rosa, Alejandro and Beatriz, who bring with thee / Jest and youthful jollity, / Quips and cranks, and wanton wiles, / Nods, and becks, and wreathed smiles.

And for Sean, who taught me what it means to read, and accompanied my wandering steps and slow.

T o begin, a man in a chair; Take One . The chair is of medium height, fashioned from dark wood, tendrils of ornamentation carved across its top and sides a set of cartouches, and in the centre a flower that digs into the nape of the mans neck. He too is of moderate stature, in his mid fifties, light brown hair tending now to grey as it frames his oval face; the skin pale and surprisingly delicate, its smoothness belying his years. Only the hands, gripping the arms of the chair harder than they need to, betray the suffering that the calm exterior works to suppress. The knuckles, rough with calluses, twitch and lock in response to the lances of pain that zigzag up through the body from his gouty legs. No sign of this suffering registers in the brown eyes that stare ahead, undistracted by any shadows or flickers of movement at the window or wainscot. Though their whites and irises look perfectly clear, it is a decade since first the left eye and then the right began to register blank spots and whole areas of fuzzy indistinction before giving way to darkness altogether.

As always at such times, he sings a quiet song to himself beneath his breath, forcing his gnarled knuckles to move and tap along to the tune. This is the hard part the everyday paradox of trying to go to sleep, knowing that the only way is not to try at all, to let ones mind wander in the secret hope that sleep will itself sneak up and pounce. Its nine oclock in the evening long gone are the schooldays when he would stay up into the early hours, often until midnight or one oclock, feverishly scribbling. He has eaten little since a light dinner, concerned that cramming his belly will lead to more of the violent rumblings that used to grip his gut after the evening meal in the years before he went blind. Never one to eat much, his appetite has now dwindled almost to nothing. Impossible to make oneself sleep, to draw an end by force of will to the stream of sensations and associations slipping by. Dangerous, too: every schoolchild knows that sleep is when the recumbent body is most vulnerable to threats from without and within, from hags and imps that suck the breath from babies, from lustful thoughts that bubble up and tarnish even the most carefully managed mind. Gradually, imperceptibly, wakefulness gives way.

At first it seems to him that there is nothing, then, suddenly, something a crackling and sparking at the edge of the mind. Later, when he wakes, it will be impossible to remember just how it happened. Time would seem not to stop, but never to have started; words like before, after, now seemed flatly irrelevant. Sometimes it would seem like it had been a fissure in the darkness, a glimmer of red or lilac light; sometimes akin to a taste, sweet and salt at once, that would tingle the tongue not altogether pleasantly, a taste new and tart like the lurid fibres of a pineapple. Most often, though, it would seem to begin as a sound, first a far-off rumbling like the trembling skin of a beaten bass drum or of brewing thunder, that would gradually, without it being possible to decide when the tremors had resolved themselves into words, form itself into a sort of speech. These were the best nights, when the words arrived, picking up the thread that had been cut that morning at the moment of waking.

When his clear unseeing eyes opened, the words would seem to vanish but he would instantly know whether they were still there, waiting to be found and fashioned. Gone for now from the mind, they had settled in the belly, as if restricting himself to a meagre dinner the previous night had been necessary to leave room for them to come. But, just like sleep itself, the words themselves could not be sought by force of will, no matter how tempting it was to try. By now he knew it was better to sit and wait. He could not see the darkness in the room beyond the window at this early hour probably four or five oclock, the usual time of his return to the waking world but he called out into it, waiting for the slap of footsteps in response that would announce the approach of his

Take Two. The scene is similar, almost identical. The chair, in fact, is exactly the same the same hefty wood and careful carvings. The man also looks similar, but there are differences. This time he is dressed not in a flowing grey coat but in tighter-fitting clothes of black. Despite his unseeing eyes, there is a small sword with a silver hilt tucked through the band at his waist and the eyes themselves are equally clear and unblemished in their shine, but they are no longer brown, rather a cooler blue-grey. Hes the same height as before but considerably stockier, which makes him look rather less tall short and thickset would be an unkind way to put it, but at least some of the bulk is muscle, suggesting that before he lost his sight and his hands curled into painful knots he would have known well how to use the sword. He again eats little, and enjoys his pipe and cup of water before settling into the chair for the evening, but rather than pursuing sleep he puts it off, enjoying the small noises of quiet and solitude, the gentle rustling of the green hangings that cover the walls. Time to think. The great work that he has known, for longer than he can remember, he was destined to achieve is finally underway, flowing freely each morning when he has had time to ruminate upon its latest part. The quiet between the hubbub of the day and the dimly punctuated blankness of sleep is when it happens. He can return to where he left off as easily as if it were a speech that he had paused momentarily for a sip of water or to clear his throat. There it is: and with the Center mix the Pole. What does he need for what comes next? He knows that it will be there when he turns to look for it.