Contents

Guide

Page List

for Simten Gurac

THE FRUIT OF USURY

TYRANT SPELLS

SAMSON SYBARITICUS

REVOLUTION AND ROMANCE

WAR ON TWO FRONTS

KILLING NO MURDER

UXORIOUS USURERS

BLIND MANS BLUFF

Rouze up O Young Men of the New Age! set your foreheads against the ignorant Hirelings! For we have Hirelings in the Camp, the Court, & the University: who would if they could, for ever depress Mental & prolong Corporeal War. Painters! on you I call! Sculptors! Architects! Suffer not the fashonable Fools to depress your powers by the prices they pretend to give for contemptible works or the expensive advertizing boasts that they make of such works; believe Christ & his Apostles that there is a Class of Men whose whole delight is in Destroying.

WILLIAM BLAKE, Milton

We did not fall because of moral error; we fell because of an intellectual error: that of taking the phenomenal world as real.

PHILIP K. DICK, VALIS

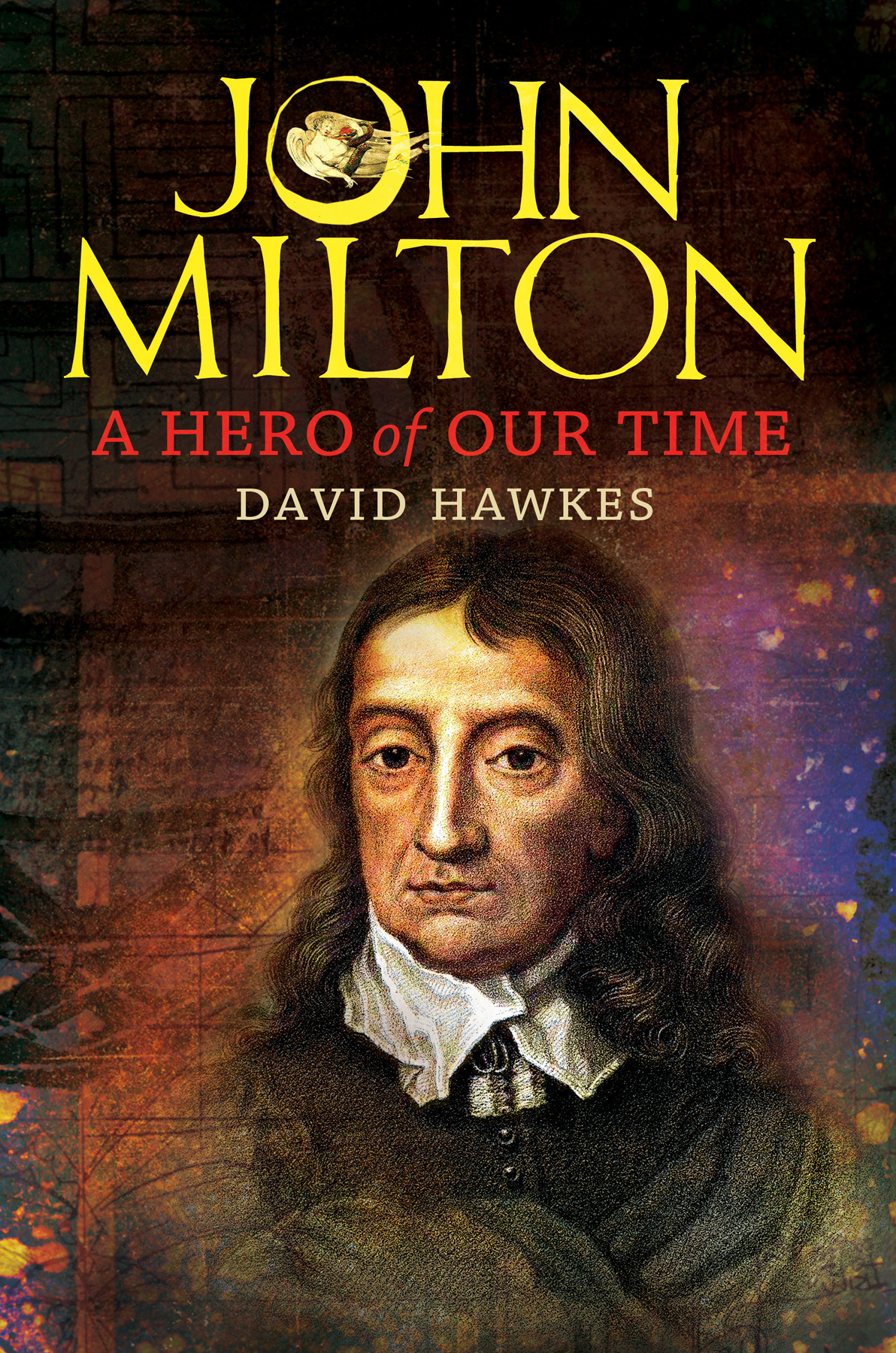

THERE ARE MANY brilliant and exhaustive biographies of Milton already. What is different about this meager essay? Most previous works on the subject have conscientiously attempted to place Milton in the context of his time. That is of course a prerequisite of a successful biography, and I hope that this one does not neglect it. The debt I owe to the historical insights provided by earlier biographies is obviously incalculable. But I have tried to make my emphasis slightly different, insofar as I concentrate on what Milton has to tell us about our own time: the postmodern era of the twenty-first century. I hope that I may be acquitted from the charge of anachronism on the grounds that Milton considered himself a prophet and that he often explicitly states that he is speaking to the people of the future, to us.

Most of the interpretations of Miltons work found here have been made before by others, and my intellectual obligations are so great as to render any invoice risibly inadequate. But I would mention in particular the work of Victoria Silver, who first taught me about Milton in graduate school, and whose book Imperfect Sense: The Predicament of Miltons Irony has influenced my ideas in ways so profound that I am doubtless unaware of many of them. The original idea for this book came from my astonishingly generous colleague Ayanna Thompson, who was also kind enough to read and comment on portions of the work in progress. Kathy Romack, Rebecca Steinberger and Barbara Traister were especially inspiring conversationalists, and I learned a great deal from them. Obviously, however, no one but myself bears any responsibility for my hermeneutical and historical blunders.

I wish to thank the English department at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, which provided me with a very useful Humanities fellowship just as I was finishing this project. The intellectual and personal generosity of Swapan Chakrovorty, Supriya and Sukanta Chaudhuri, Amlan Das Gupta, and Malabika Sarkar was truly overwhelming. The entire department of English at Arizona State University also deserves my thanks, and Ive benefited in particular from the conversation and collegiality of Cora Fox, Joe Lockard, Richard Newhauser and Brad Ryner. Phillip Karagas, Risha Sharma and Karen Silva have been unbelievably patient and helpful, and Neal Lester has unfailingly provided every aid and support I either asked or hoped for. I am extremely grateful to Eileen Cope for her initial faith in this project and her encouragement as I worked to complete it. Jack Shoemaker and Laura Mazer have been everything an author could possibly desire in a publisher. My friends and family have been staunch in their support as always, and this project could never have been conceived, let alone completed, without the unfailing loving kindness of Simten Gurac.

I

ALTHOUGH HE HAS been dead more than 300 years, John Milton should be judged by the standards of the twenty-first century. We ought to evaluate his work by its relevance to our situation today. Other authors of the past do not invite this demanding kind of scrutiny, but Milton insists on it. Throughout his life, Milton claimed to be a prophet. He frequently declared that he was speaking primarily not to his contemporaries (whom he thought hopelessly ill-equipped to understand him) but to the people of the future, to us. He believed himself divinely ordained to announce truths that might be ridiculed by his own era but that would be resoundingly vindicated by succeeding ages. He thought he was ahead of his time. He arrived early at this belief, and he never wavered from it. At the age of twenty-two he envisioned for himself a life of study and contemplation [t]ill old experience do attain / To something like Prophetic strain. His later pronouncements on the subject dispense with the qualifier. We are his intended audience; we are the ones who can judge the accuracy of his predictions. Does Milton explain the nature of our own predicament, does he indicate how it came about, does he offer a way out of it? Was he a prophet?

Prophets are not honored in their own countries, and Miltons opinions were not highly esteemed by most of his contemporaries. His views on matters ranging from monarchy to divorce were considered wildly outlandish by all but the extreme avant-garde, and the books in which he expressed them were received with furious outrage and ribald laughter. Many writers would have concluded that there was something eccentric or incoherent about their own opinions, but Milton concluded that it was everyone else who was wrong. He was, he thought, battling against the spirit of the age itself, the zeitgeist:

I did but prompt the age to quit their clogs

By the known rules of ancient liberty,

When straight a barbarous noise environs me

Of owls and cuckoos, asses, apes and dogs.

To quit their clogs means to leave their shackles, and Milton spent his life trying to break what his admirer William Blake was to call the mind-forgd manacles in which, he believed, his countrymen had imprisoned themselves. His battles were largely lost and his life ended with all of his causes defeated, but rather than question the virtue of those causes, he blamed the servile mentality of his fellow Englishmen. Attempting to liberate willing slaves was merely casting pearl to hogs. The people loved their shackles.

Milton believed that most people are natural slaves. He got this idea from Aristotle, who used it to rationalize ancient Greek societys dependence on slave labor. In Aristotle, a slave is a person whose actions serve the purposes of somebody else: a person whose own activity is alien to him, because it belongs to another. By serving the purposes of another he ceases to belong to himselfhe becomes an attribute, a property, of the other person. Serving alien purposes is unnatural, because it is human nature to pursue ones own purposes, but many, perhaps most, people are attracted to this unnatural way of life. These people would rather be slaves than be free.

It is easy to dismiss the concept of natural slavery as a piece of self-interested fiction. Of course the ruling class in a slave-owning society will need to believe that slaves are naturally suited to their condition. But Milton was well aware that legally enslaved people are not necessarily natural slaves and that many natural slaves are not legally enslaved. The Aristotelian argument describes the nature of servility, not the empirical characteristics of slaves. Milton believed that every individual was naturally inclined toward mental slavery. Not everyone acted on his or her natural inclinations, however, and in fact a virtuous life should be a continuous act of resistance to slavish temptations. For Milton, virtue was not innate but had to be actively produced, manufactured through the battle against vice, just as good is created by the fight against evil, and freedom is won only through incessant internal and external war against our natural tendencies to slavery.