ALSO BY ROLAND PERRY

Fiction

Programme for a Puppet

Blood is a Stranger

Faces in the Rain

The Honourable Assassin

The Assassin on the Bangkok Express

Non-fiction

The Queen, Her Lover and the Most Notorious Spy in History

Horrie: The War Dog

Bill the Bastard

The Fight for Australia (aka Pacific 360)

The Changi Brownlow

The Australian Light Horse

Last of the Cold War Spies

The Fifth Man

Monash: The Outsider Who Won a War

The Programming of the President

The Exile: Wilfred Burchett, Reporter of Conflict

Mel Gibson, Actor, Director, Producer

Lethal Hero

Sailing to the Moon

Elections Sur Ordinateur

Bradmans Invincibles

The Ashes

Millers Luck: The Life and Loves of Keith Miller, Australias Greatest All-Rounder

Bradmans Best

Bradmans Best Ashes Teams

The Don

Captain Australia: A History of the Celebrated Captains of Australian Test Cricket

Bold Warnie

Waughs Way

Shane Warne, Master Spinner

Documentary films

The Programming of the President

The Raising of a Galleons Ghost

Strike Swiftly

Ted Kennedy and the Pollsters

The Force

First published in 2017

Copyright Roland Perry 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 76029 143 3

eISBN 978 1 76063 979 2

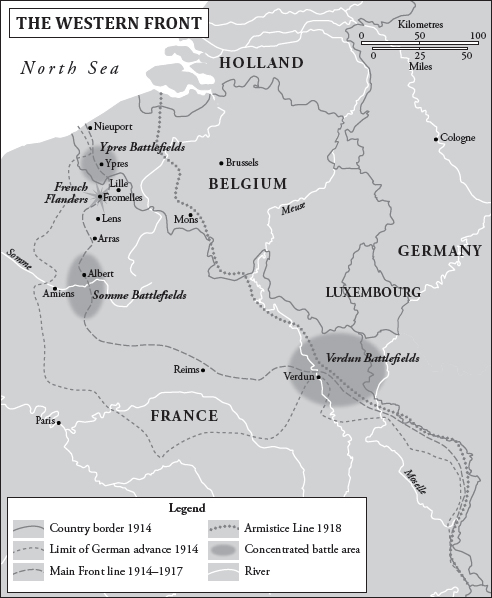

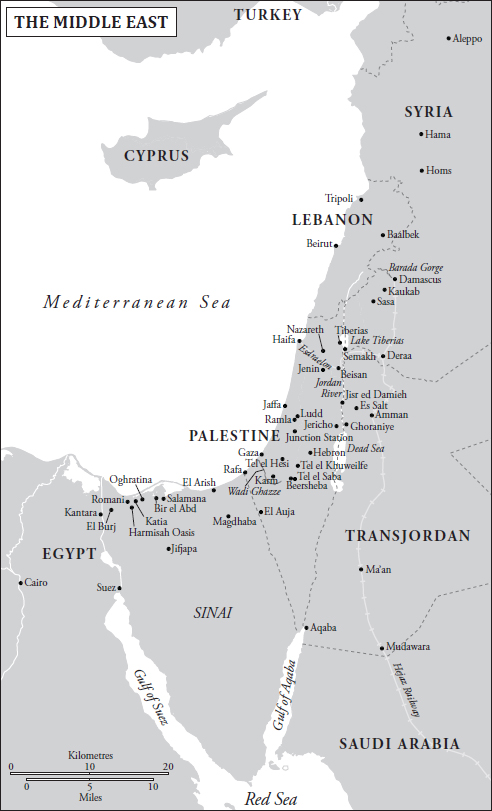

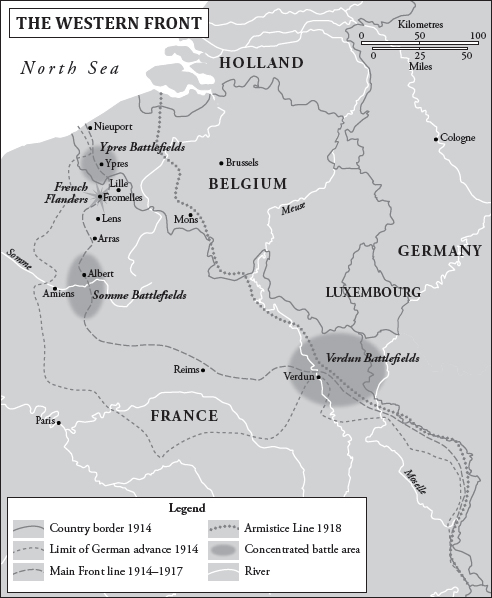

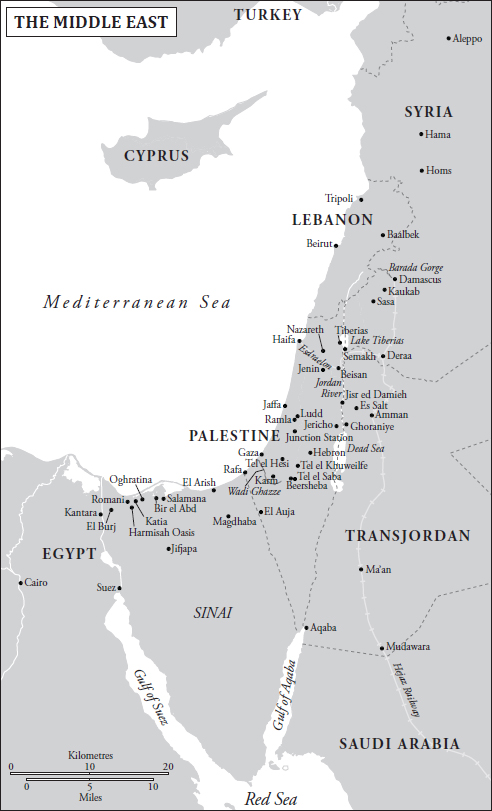

Maps by MAPgraphics

Index by Puddingburn

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

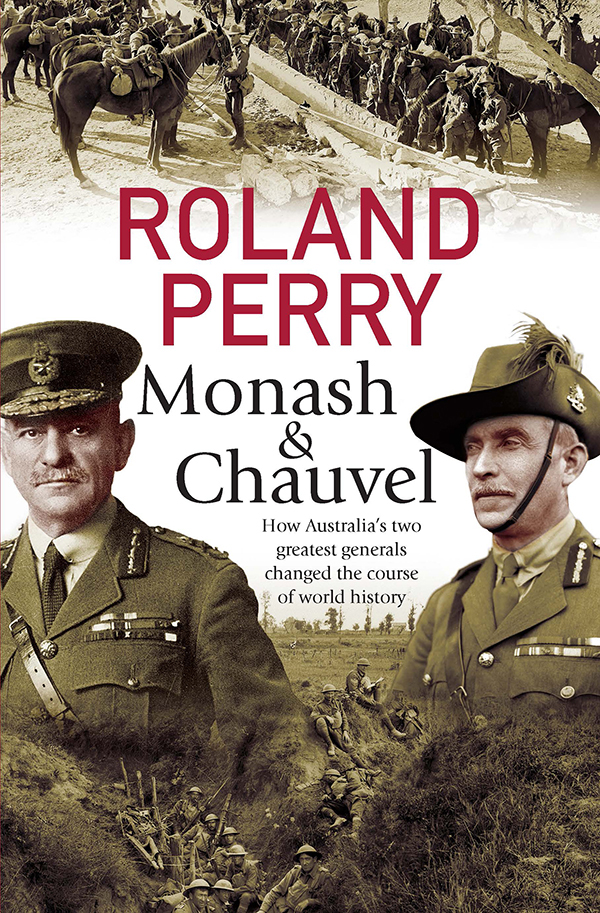

Cover design: Nada Backovic

Cover photographs: Portrait of Lieutenant General Sir John Monash (left; AWM neg no. A02697); portrait of General Sir Henry George Chauvel (right; AWN neg no. J00503); Australian 6th Battalion during the advance towards Lihons, 1918 (bottom; AWM neg no. E02866); Australians of the Anzac Mounted Division at the foot of Mount Zion, 22 January 1918 (top; AWM neg no. B01518).

To former Australian Deputy Prime Minister Tim Fischer AC, who initiated the drive to make Monash a field marshal.

To Major General Jim Barry AM, MBE, who increased the awareness of Monashs achievements in the Great War.

Contents

One bullet from a Yugoslav nationalist on 28 June 1914 killed the heir to the Austrian throne and led to a billion more being fired over the next 53 months to 11 November 1918. In that time about 10 million combatants and 7 million civilians were killed in what became known as the Great War. When Archduke Franz Ferdinand was slain, nations lined up on two sides, almost in some cases as if they could not wait to fight. The Princes death, it seemed, was a convenient excuse. Austria-Hungary delivered an ultimatum to Serbia. After a month, the Austro-Hungarians declared war on Serbia and invaded it. Russia mobilised in support of Serbia. The Germans were the most belligerent, having stepped up their preparedness over the previous decade with development and stockpiling of weaponry, particularly artillery. With victory in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 fading from memory, it wanted fresh successes, conquests and territorial gains. Germany lined up with Austria-Hungary to form the Central Powers. It invaded neutral Belgium and Luxembourg, before moving towards France. The United Kingdom reacted by declaring war on Germany.

These alliances drew in more nations as the war spread: Italy, Japan and the United States joined the Allies (the United Kingdom and France), while the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria joined the Central Powers.

The war had three interwoven explanations. First, it was a line-up of empires all searching for control and survival in a changing world. Second, there was conflict within a family of royals, the grandchildren of the United Kingdoms Queen Victoria: Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, Russias Tsar Nicholas II and the United Kingdoms King George V. Wilhelm II was the belligerent of the three, who imagined that his two cousins, in fact most of the extended royal family, were against him. If these three had come to a rapprochement, war may have been avoided. But there was too much enmity between Wilhelm II and the others. There was no serious diplomatic will between them. They could not agree. Had Queen Victorias son King Edward VII, the so-called peacemaker, been alive, events may have been different. But he had died in 1910. Their nations went to war.

A third factor was the old world of dictators and monarchies versus the growing, still fledgling new world of democracies. If the German military dictatorship won, the world would slip backwards into a dark period. If the British and French democracies emerged victors, then there was a chance that democracies would take a greater hold on progress.

The United Kingdom drew on the resources of its vast empire, including 650,000 Dominion (former colonial) soldiers, who would fight in Europe and the Middle East. In Australia 415,000 people (from a population of 4 million) were mobilised and employed in military service over the wars duration.

Among them were two outstanding battle commanders who would lead the most successful armies of the war. One was Harry Chauvel, who led the 34,000-strong Desert Mounted Column in the Middle East, which consisted of 75 per cent Anzac Light Horse. Chauvel was an empire man, who considered himself as British first, Australian second. His attitude changed over the course of the war as he realised that no matter what was achieved, he would receive more lasting recognition in his homeland.

The other great commander was John Monash on the Western Front in Europe, who at the peak of the deciding year of 1918 commanded the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). It had 208,000 soldiers (more than six times Australias current defence force), and was the biggest single army corps of the twenty on the Allied side. He saw himself as Australian first and second. He viewed the war on the battlefields as that between two systems: military dictatorship and emerging democracy. His German lineage meant fewer ties to the British Empire and he had a real sense of Australias needs as an independent fledgling nation. His background also made him more aware than any other Allied general of what was at stake.

Australian generals John Monash and Harry Chauvel were poised with their armies early in 1918 to have a real impact on the two major battle areas of the Great War. At the beginning of that fateful year, Monash was running a division of 30,000 soldiers on the Western Front in northern France. Before mid-year, he would be commander-in-chief of the First Australian Imperial Force, the biggest of the twenty army corps on the Allies side, when the nations five divisions would come together as one fighting unit for the first time ever.