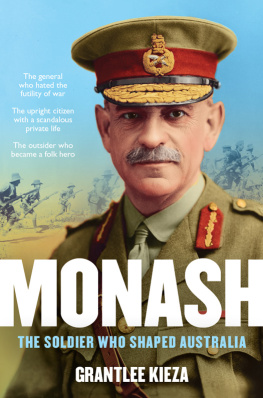

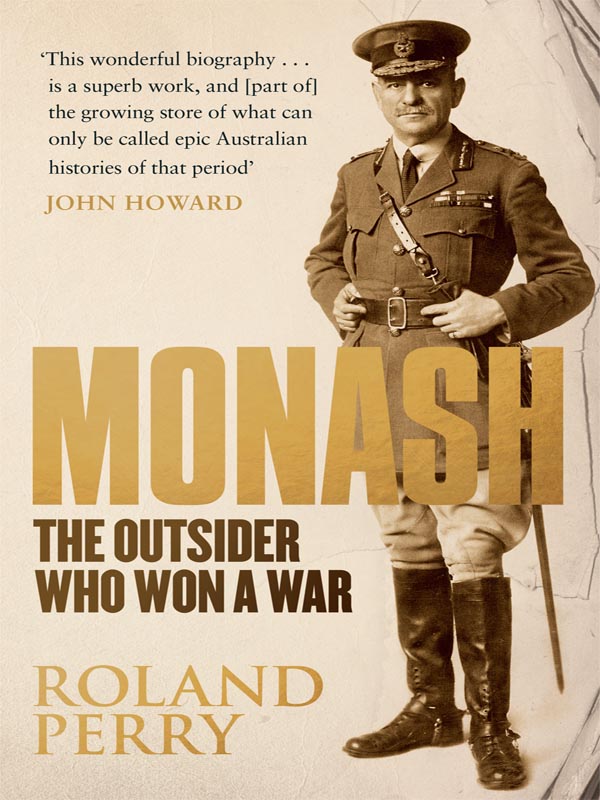

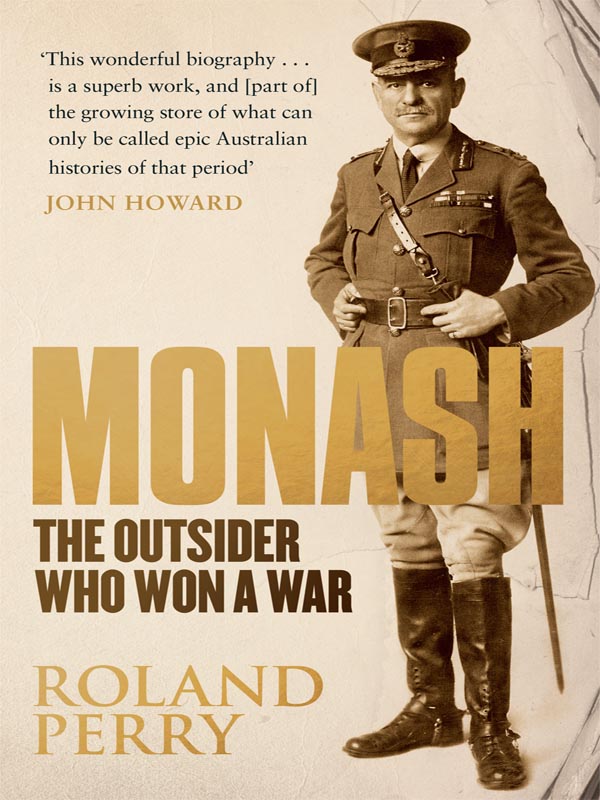

About the Book

Australian general Sir John Monash changed the way wars were fought and won. When the British and German high commands of the First World War failed to gain ascendency after fours years of slaughter never before seen in human history, Monash used innovative techniques and modern technology to plan and win major battles, forcing Germany to capitulate. His obsessional, brilliant planning, coupled with a ruthless streak, caused him to break the German army in a succession of battles that led to the end of the Great War.

Author Roland Perry brings to life the fascinating story of the man whom many have judged as the greatest-ever Australian. Monash: The Outsider Who Won A War draws on the subjects comprehensive letter and diary archive - one of the largest in Australias history. The result is a riveting portrait that reaches to the heart of the true Monash character. It weaves together the many strands of his life as a family man, student, engineer, businessman, lawyer, renaissance man, teacher, soldier, leader, romantic and lover of the arts.

Contents

To Major Warren Perry

and the memory of Tim Burstall

List of Maps

Gallipoli. The Hamilton plan saw a double invasion at Cape Helles by mainly British Forces, and Anzac Cove by mainly Anzac Forces.

Australian Positions Held at Anzac Cove from 26 April 1915 . Anzac forces attained these positions by the second day of the invasion 26 April. No further territory was taken beyond the arc above Anzac Cove until evacuation eight months later.

The August Offensive 1915: The Battle of Sari Bair: The Left Hook Attempt by Monashs 4th Brigade. Hamilton and Birdwood decided to break out of the locked-down Anzac Cove by advancing north in a semi-circle heading for Hill 971, held by the Turks.

The Flanders Campaign 1917: Battles of Monashs 3rd Division. John Monashs 3rd Division in 1917 was part of successful British attacks on German-held Messines and Broodseinde. Haigs insistence in attacking during atrocious conditions in October at Passchendaele ensured defeat.

Advances of Monashs 3rd Division during March, April, May, June & July 1918. Monashs 3rd Division took a stand against the German advance on 27 March 1918, held the line and gradually pushed the enemy back.

Battle of Hamel: 4 July 1918 . Monash gave new meaning to the expression military precision with his planning to take Hamel. His use of tanks at night, and various tactics such as smoke and noise screens, along with a minimum of casualties, presaged the way he would attempt to win the war for the Allies. He had a deadline. In three months, the 191819 winter would set in.

Battle of Amiens on 8 August 1918, Spearheaded by the Australian Corps. Monash reached the peak of his powers as a battlefield commander with the success of his troops in crashing through the German lines on 8 August 1918.

Battle of Chuignes and Bray, Spearheaded by AIFs 3rd Division, 23 August 1918. Monashs success on 23 August 1918 in taking Chuignes and Bray convinced him he could obliterate the enemy if given the opportunity.

The Battle for Pronne and Mont St Quentin, 31 August 3 September 1918 Exclusively by AIFs 2nd, 3rd and 5th Divisions . Fourth Army Chief Rawlinson scoffed at Monashs conviction that the AIF on its own could take Mont St Quentin and Pronne with remnants of his battle-weary 2nd, 3rd and 5th Divisions. Monash proved correct in the toughest close combat by the Australians in the push to the Hindenburg Line.

The Australian Corps Campaign in France: 4 July 5 October 1918. The AIF spearheaded the last three months of battles by the British forces from Amiens to Montbrehain, winning every major battle. This forced the Germans to sue for peace.

Battle for Hargicourt and Hindenburg Outpost Line, 18 September 1918, Spearheaded by AIFs 1st and 4th Divisions. The AIFs sense of invincibility continued on 18 September with the smashing of the outer shell of the Hindenburg Line the nine-kilometre-wide, eighty-kilometre-long German defence system. Monashs use of dummy tanks, among his many tricks, caused the quick capitulation of the enemy.

Breaching of the Hindenburg Defences by AIFs 2nd, 3rd and 5th Divisions with the US 27th and 30th Divisions, 29 September 5 October 1918. Monash pushed his troops one last time to break the complete Hindenburg fortification with the help (and hindrance) of the American forces. The last battle, by the 2nd Division, to take Montbrehain further east, was an unnecessary fight too far for the AIF ordered by Haig and Rawlinson.

ENGINEER OF VICTORY: 8 AUGUST 1918

Lieutenant General Sir John Monash, the commander of the Australian Corps, paced the 130-metre drive of his HQ, the Chteau de Bertangles, from its steps to its medieval front gates. It was just after 4 a.m. on 8 August 1918. The night sky was black except for the odd artillery shell. Planes buzzed overhead, drowning the squeal of tanks beginning their crawl forward like giant armadillos. The air was heavy with pungent wafts of fuel, smoke and earlier gas attacks. In less than twenty minutes, the five Australian divisions under his command east of Amiens on the Western Front in France would fight together for the first time in war. They would be the spearhead of the massive Allied offensive against the German Army.

There was more than an edge of anticipation in Monashs step as he glanced at his watch every few minutes. His movement along the path and agility up and down the chteau steps were those of a man half his fifty-three years. The build-up to this most important battle of the war had seen him shedding weight until his frame was as lean and hard as that of any commander in the field. His face would never betray nerves or fear. Monash had trained himself that way.

This event on 8 August was the most important in Australias history, next to 25 April 1915, when the Anzacs had landed at Gallipoli. Monash more than anyone else would foster the importance of that day during the disastrous invasion of Turkey, which marked Australias entry into the war. But his expectations as the man in charge of this attack were greater. Heroic stalemate and honourable retreat would not be enough here. Nothing short of a smashing victory would do.

Monash had unbounded faith in the fighting capacities of his troops, who formed the biggest corps on the entire Western Front. In turn, the soldiers had a growing faith in their commander. He had a reputation, in modern parlance, as a winner. Monashs planning was seen first when he organised the defence of Monash Valley at Gallipoli. Then 40,000 Turks in the hills above had been set against 12,500 Anzacs locked in an arc beyond the beaches below. His approach to preparation was perfection to the point of obsession unmatched in the annals of military history. His concern that his soldiers should not be used in unnecessarily dangerous operations had filtered through to every digger at the front. His attitude was diametrically opposed to the apparent men as cannon fodder, bumbling battle philosophy of the British High Command. This approach had seen hundreds of thousand of soldiers sacrificed in the war. The British Army had not had a decisive win until Monash took charge of the Australians in mid-1918.

He was as ruthless as any commander on either side. But it was anathema to him to fight unless he had prepared so meticulously that he was certain of victory. Anticipation of a huge breach of the German defences only minutes away before dawn set him on edge on this cool summer morning. This was his biggest battle so far.