PRAISE FOR JEROME CHARYN

One of the most important writers in American literature. Michael Chabon

One of our finest writers.... Whatever milieu [Charyn] chooses to inhabit,... his sentences are pure vernacular music, his voice unmistakable. Jonathan Lethem

Charyn, like Nabokov, is that most fiendish sort of writerso seductive as to beg imitation, so singular as to make imitation impossible. Tom Bissell

Among Charyns writerly gifts is a dazzling energy.... [He is] an exuberant chronicler of the mythos of American life. Joyce Carol Oates, New York Review of Books

A fearless writer.... Brave and brazen. Andrew Delbanco, New York Review of Books

Charyn skillfully breathes life into historical icons. New Yorker

Both a serious writer and an immensely approachable one, always witty and readable and... interesting. Washington Post

Absolutely unique among American writers. Los Angeles Times

A contemporary American Balzac. Newsday

PRAISE FOR The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson: A Novel

Daring. New York Times Book Review

Audacious.... Seductive.... Charyn has never written more powerfully.... A poignant, delicately rendered vision. New York Review of Books

Through a perceptive reading of Dickinsons verse and correspondence, [Charyns] re-created her wild mind in all its erudition, playfulness and nervous energy. Washington Post

Compellingly drawn.... I admire Charyns achievement in lifting the veil of a heretofore mysterious figure. Los Angeles Times

In this brilliant and hilarious jailbreak of a novel, Charyn channels the genius poet and her great leaps of the imagination. Booklist (starred review)

In his breathtaking high-wire act of ventriloquism, Jerome Charyn pulls off the nearly impossible: in The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson he imagines an Emily Dickinson of mischievousness, brilliance, desire, and wit (all which she possessed) and then boldly sets her amidst a throng of historical, fictional, and surprising characters just as hard to forget as she is. This is a bold book, but wed expect no less of this amazing novelist. Brenda Wineapple, author of White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

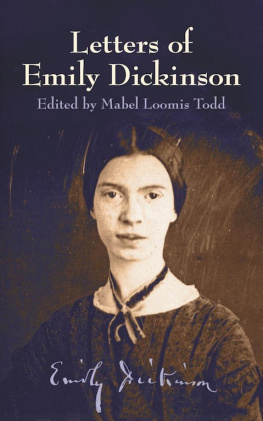

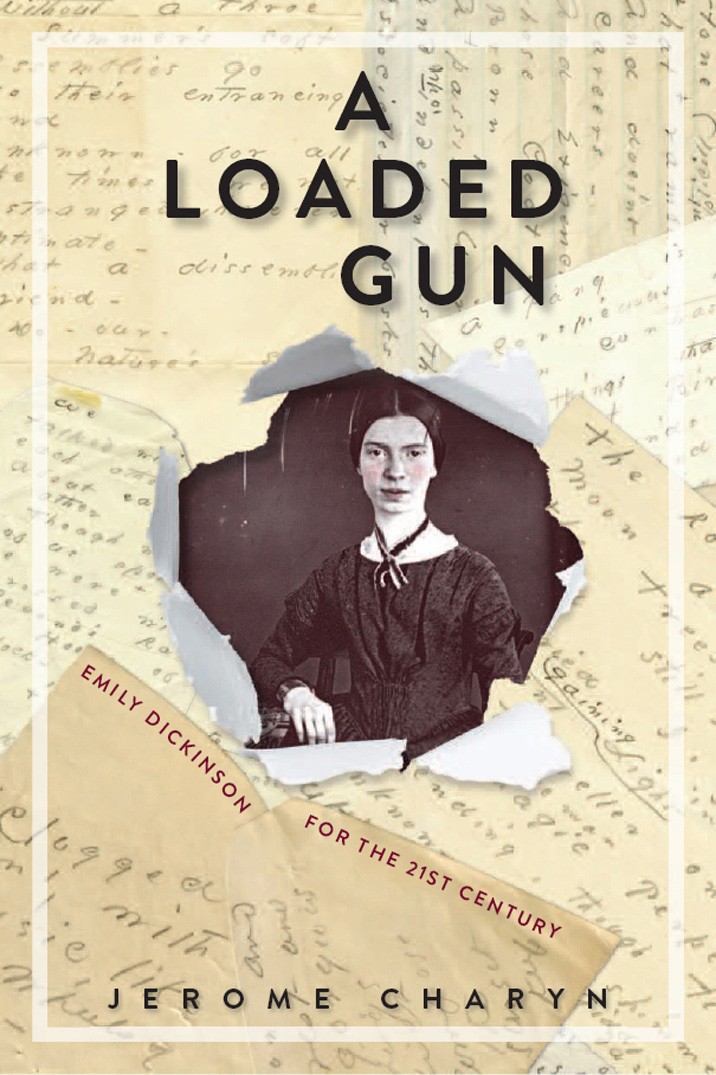

The poet (left) and one of her possible muses, circa 1859 Used by kind permission of a private collector

First published in the United States in 2016 by

Bellevue Literary Press, New York

For information, contact:

Bellevue Literary Press

NYU School of Medicine

550 First Avenue

OBV A612

New York, NY 10016

2016 by Jerome Charyn

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the publisher upon request

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a print, online, or broadcast review.

Cover images courtesy of The Emily Dickinson Collection, Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

Bellevue Literary Press would like to thank all its generous donorsindividuals and foundationsfor their support.

| The New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature |

| This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. |

Book design and composition by Mulberry Tree Press, Inc.

First Edition

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

ebook ISBN: 978-1-934137-99-4

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

I COULDNT LET GO. Id spent two years writing a novel about her, vampirizing her letters and poems, sucking the blood out of her bones, like some hunter of lost souls. Id rifled through every book about her I could findbiographies, psychoanalytic studies of her crippled, wounded self, tales of her martyrdom in the nineteenth century, studies of her iconic white dress, accounts of her agoraphobia, etc. I shut my eyes, blinked, and wrote The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson (2010), like a boy galloping on a blind horse. I never believed much in her spinsterhood and shriveled sexuality. Yet she was a spinster in a way, a spinner of words. Spiders were also known as spinsters, and like a spider, she spun her meticulous webs, trapping words until she gathered them in a Lexicon that had no equal.

She falls in love with a handyman at Mount Holyoke in my novel. Perhaps she dreams him up in the snow outside her window, a blond creature with a tattoo on his arm of a red heart pierced with a blue arrowthat tattoo is every bit as extravagant and outrageous as her poems. Tom the Handyman could be a phantom and a whisper of her own art. Hes also a burglar and a thief, an appropriate accomplice for a woman who burgled the English language; he will rescue her in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when she roams around half-blind, and she will discover him again hiding in a circus near the end of her lifeDickinson loved the circus, with its rash of red.

The poet was also in love with Susan Gilbert, as her own letters reveal. And Sue remains the most enigmatic character in the novelvolatile, brooding, dark. She was our Vesuvius, who rained hot lava down upon our heads, as Dickinson says in my Secret Life. There are rides to eternity throughout Dickinsons poems, and I wrote about her own last ride as a voyage to her dead fathers barn, wearing a bridal gown, all done up in tulle, but she never gets therediscontinuity has always been her habit.

And thus I travel in my Dimity and tulle, but that barn could be in Peru. I seem nearer and nearer, but never near enough. My bridal gown could be in tatters before I arrive.

As Dickinson teaches us, endings have no end. She was a master of quantum mechanics long before that science was ever born. People like us, who believe in physics, know the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion, Einstein once said, and he could have been talking about Emily Dickinson. She was always at the ragged edge of time.

And there wasnt a bit of closure, even after I finished my novel. I knew less and less the more I learned about her. There was no way to shove her aside. Her poems never heal the essential wound of reading her. Even the tales of her life were tantalizing, since they reveal so little. She was an agoraphobic who could dance anywhere on her toes, a reclusive nun who wrote the sexiest love letters, a mermaid who swam in her own interior sea, a shy mouse who could pillage and plunder in her poems. All her life she was a Loaded Gun.