Contents

Guide

Page List

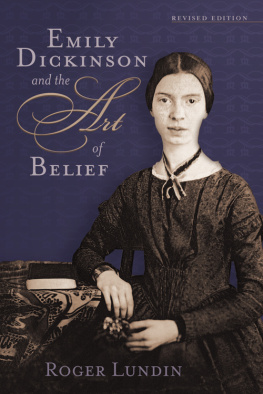

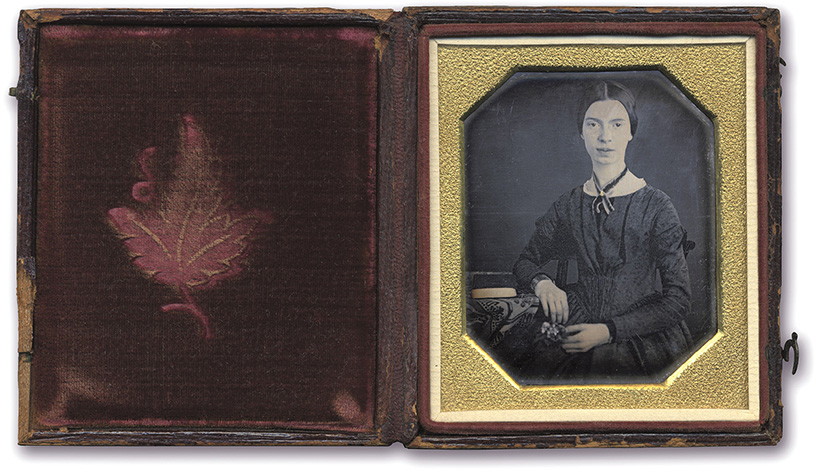

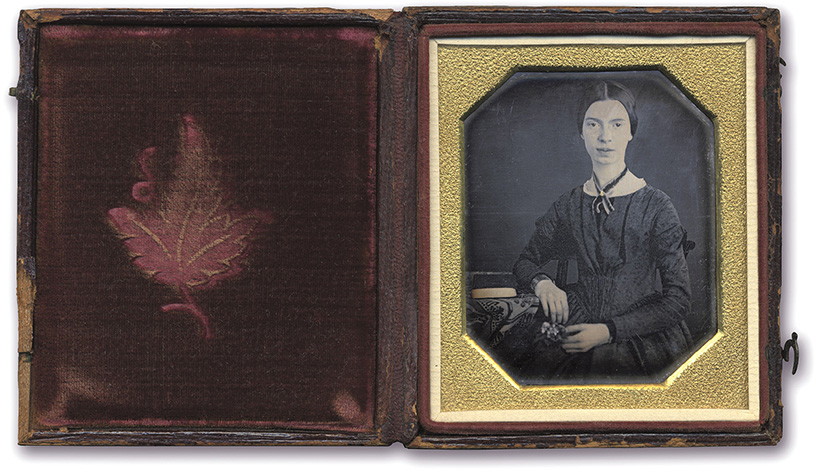

The single authenticated photographic image of Emily Dickinson, circa 1847.

Emily Dickinsons Gardening Life

The Plants & Places That Inspired the Iconic Poet

Marta McDowell

For Kirke

Or is it dancing?

Contents

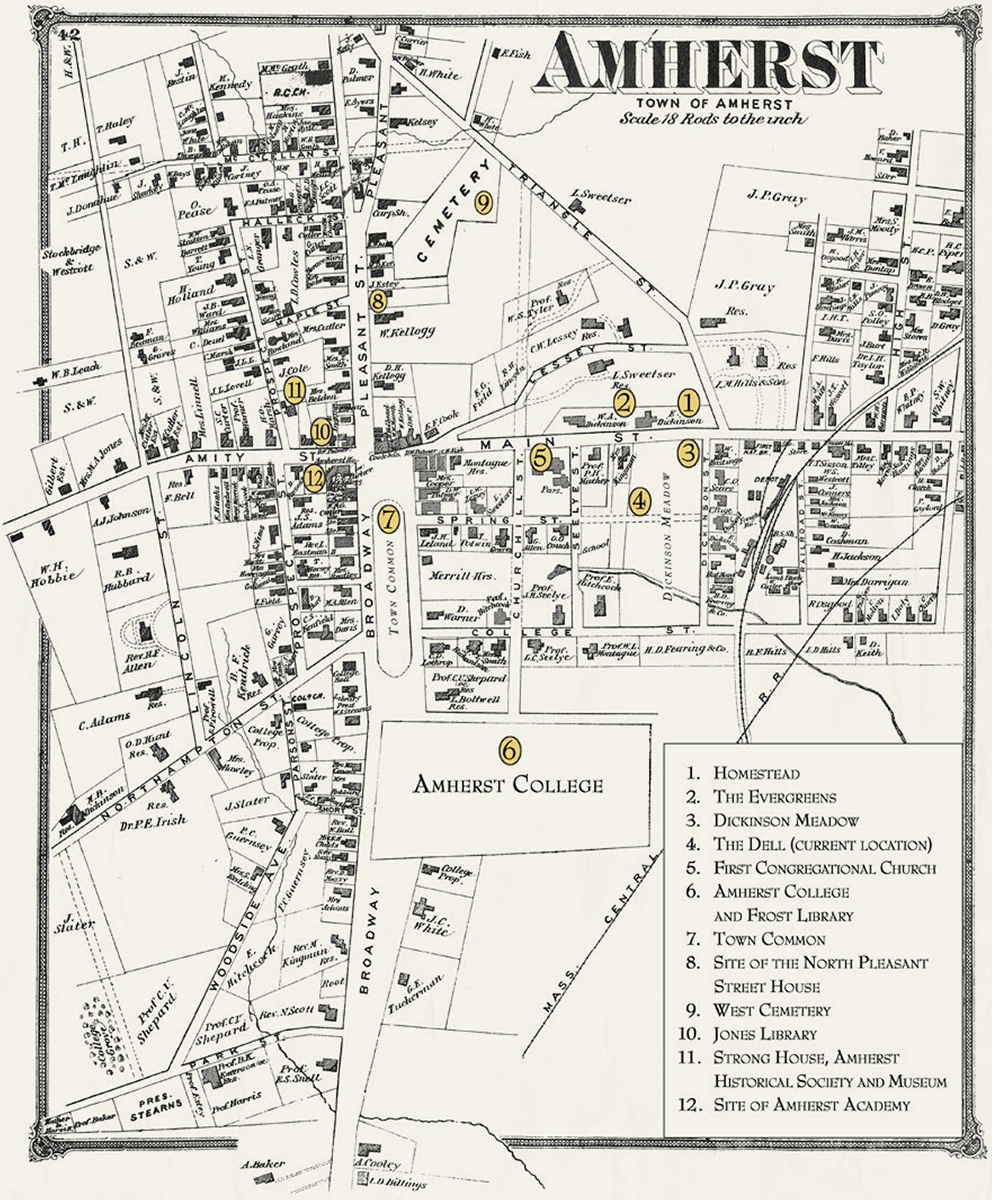

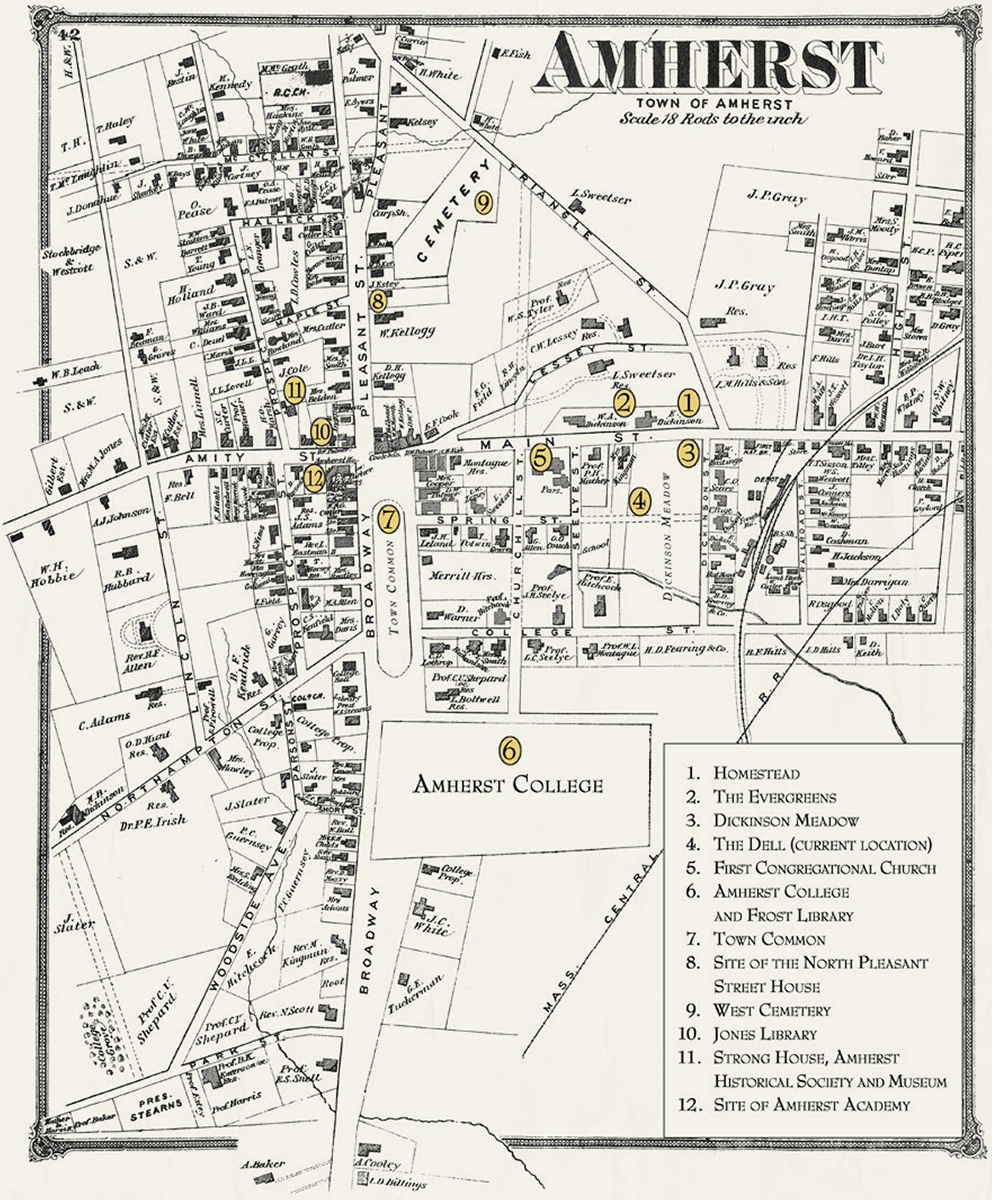

Locations around Amherst connected with Emily Dickinson, overlaid on an 1873 map.

Preface To The Revised Edition

Emily Dickinson was an accident for me, at leastin terms of her gardens and my writing. It occurred in my corporate phase, a two-plus-decade career that had sprung up, unlikely but fully clothed, after college graduation. A forty-something me in the guise of diligent insurance executive was driving solo to agencies across New England to deliver the latest management message.

It was midafternoon in summer, the 1990s, between a lunchtime meeting in Framingham, Massachusetts, and an overnight stop in Springfield. Westbound on I-90, the Mass Pike stretched across the middle of the state, shimmering in the heat. I was in dire need of caffeine. Turn signal. Ludlow Service Plaza. The rest of the day yawned ahead with the anticipated solitary dinner, anonymous hotel, and too much email. But as with interstate rest areas from sea to shining sea, a literature rack beckoned with local tourist offerings. My eyes lit on a brochure for the Emily Dickinson Homestead.

The heart of a liberal arts major still beat in my suit-clad frame. Bits of Dickinsons poems fluttered in distant memory, their own things with feathers. As the museums brochure listed the last tour at 4:00 p.m., I called from the pay phone, which now seems unspeakably quaint. A woman with the inflections of mid-Massachusetts said that yes, I would be able to make it to Amherst in time.

The drive north was bucolicthe Connecticut River with the Calvin Coolidge Bridge, rolling farmland, an absence of strip malls and traffic lights. The shady common of downtown Amherst was quiet mid-week in summer with its college students away.

The Dickinson Homestead was an encounter that seemed, well, transcendental. I learned from the guide that, like me, Emily Dickinson was a gardener. Here was her collection of pressed plants, or at least a facsimile. A photograph of her conservatory was framed on the wall of her fathers study, the same wall that used to open onto a small glass room with her shelves of potted plants. Stepping out into the wide expanse that was her garden, I started on a much longer road. Her garden became a way for me to learn, to think about her life and her poems in the context of her pursuit of plants. It was Dickinson who brought me to garden writing.

I have Tom Fischer to thank twice for smoothing the way to my pursuit of Emily Dickinsons gardens. It first came in the form of a refusal, in 1999, of an article submission to Horticulture, a magazine he then edited. He sent me the nicest rejection letter, suggesting I send the proposal on to David Wheeler at Hortus, a British gardening journal for which I still write. Almost twenty years later Tom, by then at Timber Press, and his colleague Andrew Beckman suggested this revised edition.

It is great to have a do-over for anything in life, including a book. For those familiar with the first edition, now long out of print, you will note new material and color illustrations throughout. Revisions incorporate scholarship and research since the first edition, and of course, correct and amend along the way. The new edition is reorganized. The first part of the book focuses on Emily Dickinsons life as a gardener in step with the progression of a year in her garden. The second part includes a visitors guide to the Dickinson landscape, including the Emily Dickinson Museum, which has seen major changes in the past twenty years. I hope you get a chance to visit or visit again. If you arrange your trip to coincide with one of the museums garden weekends, perhaps you will come work in the garden with me. If you want to plant a poets garden of your own, youll also find an annotated plant list.

Before we begin, a word about spelling, grammar, and punctuation. The poems and quotes from letters that youll read in this volume are taken from editions by two Harvard scholars: Ralph W. Franklinthe numbers after the poems are from his editionand Thomas H. Johnson, who carefully deciphered Dickinsons manuscripts to use her original words, transcribed directly from her pen. If the punctuation is peculiar or the spelling unusual, know that it was as she wrote it.

And now, to begin. Again.

Introduction

Emily Dickinson was a gardener.

When you hear the name Emily Dickinson, it may bring to mind a white dress or a well-known image of a sixteen-year-old girl staring boldly out of a daguerreotype. Poetry, of course. Probably not gardening.

Emily Dickinson as a gardener doesnt fit with the Dickinson mythology. The myths were based on real phobias of her later years and were also stoked by her first editor, Mabel Loomis Todd, to promote book sales. Since her death in 1886, she has been psychoanalyzed, compared to medieval cloistered mystics, and called the madwoman in the attic. All she lacked was a cloister.

Beyond the stuff of literary legend, she was a person devoted to her family, with pleasures and pastimes and deep friendships. She shared a love of plants with her parents and siblings. To friends, she sent bouquets, and to some of her numerous correspondentsover one thousand of her letters have been foundpressed flowers.

She collected wildflowers, walking with her dog, Carlo. She studied botany at Amherst Academy and Mount Holyoke. She tended both a small glass conservatory attached to the front of the house and a long flower garden sloping down the spacious east side of the grounds. In winter, she forced hyacinth bulbs and in summer she knelt on a red blanket in her flower borders, performing horticultures familiar rituals.

This book proceeds in calendar fashion, following the seasons. Welcome to Emily Dickinsons gardening year.

A daisy in Emily Dickinsons garden.