Contents

Guide

Page List

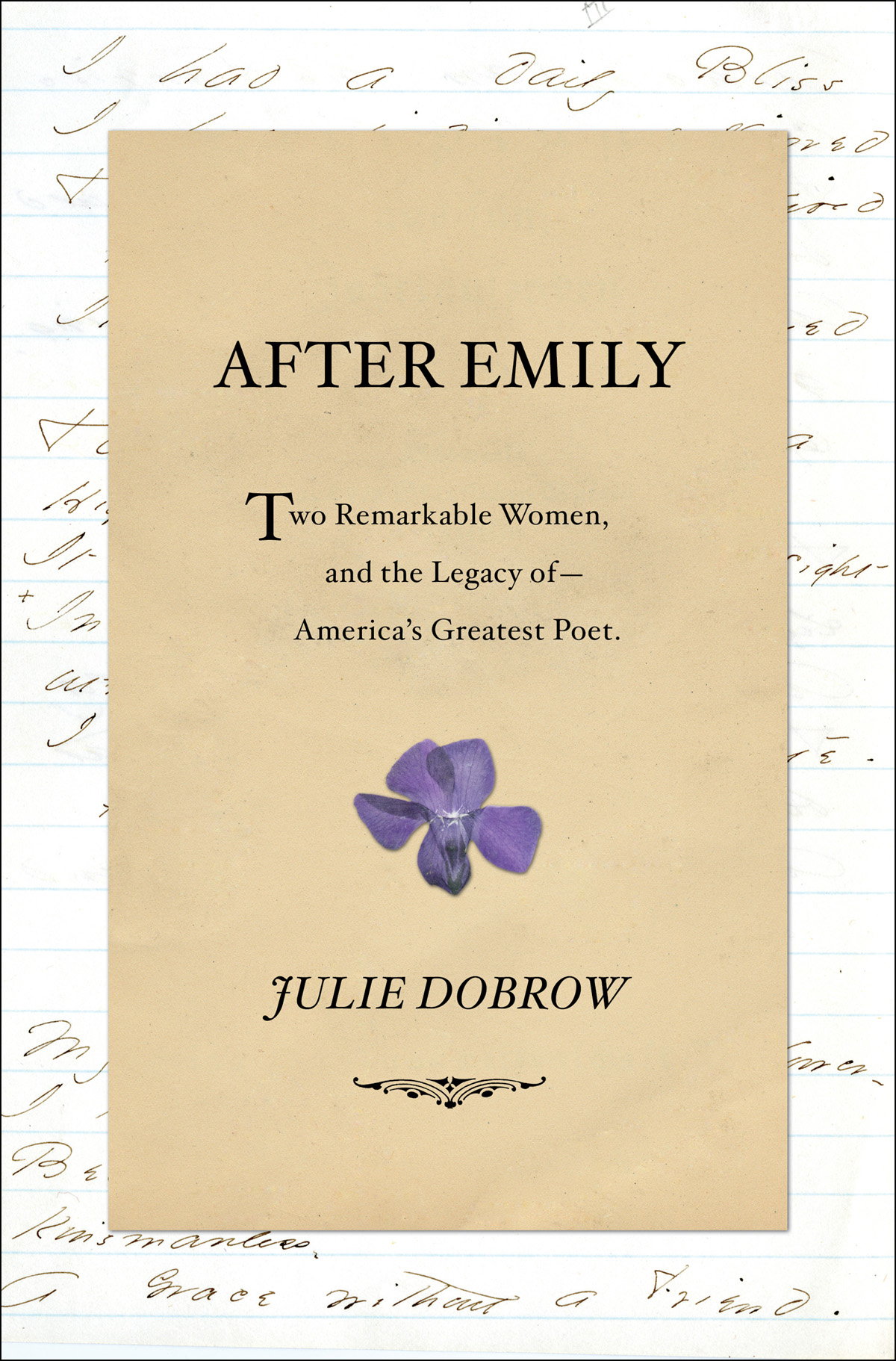

AFTER EMILY

TWO REMARKABLE WOMEN

AND THE LEGACY OF AMERICAS

GREATEST POET

JULIE DOBROW

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

For my parents and my grandmother, who first taught me to believe that

There is no frigate like a book To take us lands away

Biography first convinces us of the fleeing of the biographied

EMILY DICKINSON

CONTENTS

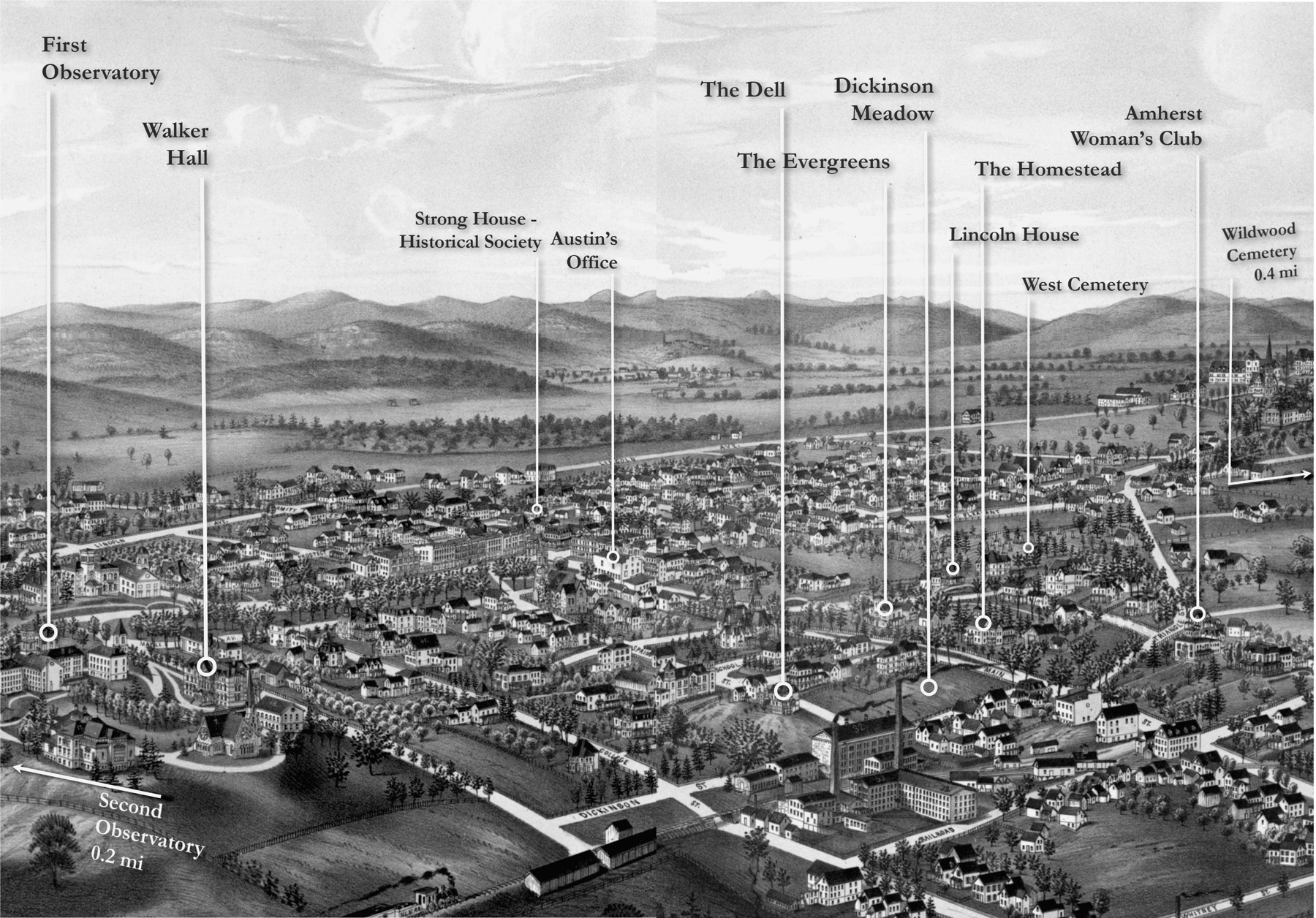

1886 MAP OF AMHERST WITH ANNOTATIONS

The most positively brilliant life

E mily Dickinson is perhaps the most beloved and the most puzzling of all American poets. Just as she held the world at arms length during her life, so has she revealed little of her true self since her death in 1886despite the devotion of countless biographical and literary detectives. As her words once prophesied:

So we must keep apart,

You there, I here,

With just the door ajar

That oceans are,

And prayer,

And that pale sustenance,

Despair!

The outlines of the poets life are fairly well-known. Emily Elizabeth Dickinson, born in 1830 in Amherst, Massachusetts, came into life as the second child of Edward Dickinson and his wife, Emily Norcross. The Dickinson family had deep roots in Amherst, their forebears having been among the original settlers in neighboring Hadley. The Dickinsons were intensively engaged in local civic affairs; Edward even became immersed in state and national politics, elected to terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives and later in the U.S. Congress as a member of the Whig Party. Affluent (though they had endured a period of economic instability), integrally tied to Amherst College (which Emilys grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, helped to found) and heavily invested in the cultural capital of the day, the Dickinson family commanded respect and admiration.

Bookended by brother William Austin (known as Austin), older by a year, and sister Lavinia (Vinnie), three years younger, Emily grew up in a household that valued independence, literature and the natural world. Biographer Richard Sewall suggests that while Emily was reared within a family and a community still clenched by their Puritan roots, Emily, herself, broke from its grip. Her sense of the past... could hardly be called vivid, he writes. Emily rejected the orthodoxy of the many religious revivals sweeping the region. She developed a caustic wit that often led her to question authority. And yet, as Sewall points out, young Emily linked a sense of wonder with the Puritan value of intellectual rigor. She embraced the Puritan tenets of hard work, practicality and intensity of purpose. She was prepared to accept the loneliness of such a course, a loneliness endemic in the New England Puritan way and intensified by her own peculiar defections.

Emilys immediate family bounded and defined her world. Her relationship with her father was complicated: when she was a child, Edwards strict, sometimes authoritarian manner led Emily to fear his reproach, but as a young woman, to rebel from or even to poke fun at his Puritan-derived ways. Yet she also deeply respected her fathers dedication to family, community and country, as well as his intellect. As Sewall writes, Emilys nuanced understanding of Edward was perhaps never more poignantly expressed than in a letter to family friend Joseph Bardwell Lyman, in which she explained her father as the oldest and the oddest sort of a foreigner, someone caught between his work and his family though fully in touch with neither, a man whose life had passed in a wilderness or on an island.

Her relationship with her mother and siblings was perhaps more clear-cut and less conflicted. By most accounts, Emily Norcross Dickinsons life centered on her home and her gardens, and she had little interest in discussing politics, philosophy or literature of the day. Indeed, her namesake daughter once wrote that her mother does not care for thought. Both girls were committed to Emily Norcross, nonetheless, caring for her in sickness and never leaving her.

Emilys relationship with Austin was extremely close when the two were young; they shared a consciousness of kind. Many of their early letters show the pair exchanged thoughts about their parents and sister, their community, ideas about philosophy and nature. After Austin married his relationship with Emily changed, but she remained dedicated to enabling his happiness in the ways she could. While no less deep than her relationship with Austin, Emilys relationship with her sister differed in significant ways. Despite the dissimilarities in personality (Vinnie was ebullient, highly social and, as Sewall notes, never noted for her profundity) and interests (Vinnie was neither a serious student nor a writer), Emilys connection with her sister was constant, loyal and dependent. She once described the bond between them as indissoluble. Lavinia both revered and respected her older sister and would remain faithfully devoted to her.

Emily received formal education at the Amherst Academy from 1840 to 1847. She then joined the ranks of middle-class nineteenth-century women who went on to college and spent a year studying at the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary when she was seventeen. She left for unknown reasons (thought having to do either with her physical or emotional health), but Emilys informal education continued at home. Emily Dickinsonvoracious reader, precise recorder of nature, enthusiastic cultivator of flowers and herbs, stalwart baker of breads and cakesobserved the world around her with unusual acuity and insight.

Though Emilys life centered on her family, she maintained a circle of friends close by and correspondents, afar. Her circle enlarged with trips to Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia in 1855, and to Boston in 1864 and 1865. Emilys friends and acquaintances were both women and men: some of the most meaningful relationships included Susan Huntington Gilbert, who would become Emilys sister-in-law when she married Austin in 1856; the Springfield Republican editor and Dickinson family friend Samuel Bowles; the Reverend Charles Wadsworth, with whom Emily corresponded though she met him on only a couple of occasions; and Judge Otis Phillips Lord, her fathers closest friend who developed an independent relationship with Emily late in his life. Its not clear whether any of these relationships also involved romantic attachment, though numerous sources indicate that some of Emilys letters, as well as references from family members in their correspondence, strongly suggest the relationship with Judge Lord had a romantic element to it. What is clear is that by the late 1860s, Emily Dickinsons contacts with people other than her immediate family occurred more through the written word than through the spoken one. She began the reclusion that would characterize the rest of her life.

By the end of that decade she barely left the confines of her own home. Neither she nor Lavinia ever married. After both of their parents died, the sisters spent the remainder of their lives living together in their cavernous family home. During the final years of her life the number of people Emily actually saw in person further dwindled, and yet she maintained significant connection to those with whom she did engage. The intensity of emotion expressed in many of Emilys letters, including the so-called Master letters, reveal other sides of a woman whose outwardly simple and reclusive life belied the complexities that lay within. Scholars have long debated whether these three passionate and highly stylized missives to an unnamed recipient addressed only as dear Master, were written to a particular person and if so, what his or her identity was. Its believed that these letters were written between 1858 and 1861. It is not known whether versions of them were ever sent. Some scholars and literary analysts insist that the intended recipient was, in fact, Judge Lord. But others suggest it was Reverend Charles Wadsworth, while some name Samuel Bowles. Still others believe that Master was scientist William Smith Clark, or Dr. George Gould, a minister and Amherst classmate of Austins. And some posit that Susan Dickinson was actually the intended recipient of the Master letters.