Contents

Guide

Page List

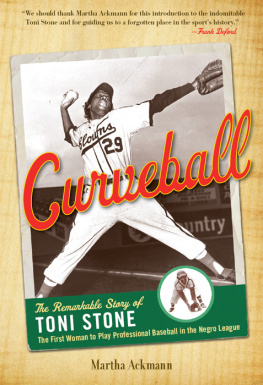

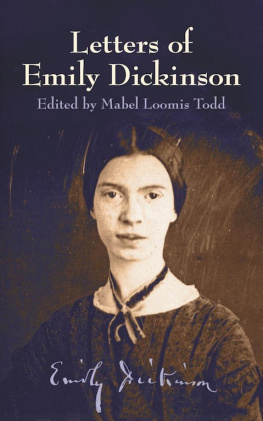

ALSO BY MARTHA ACKMANN

Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone

The Mercury 13: The True Story of Thirteen Women and the Dream of Space Flight

THESE FEVERED DAYS

Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson

MARTHA ACKMANN

FOR

JOANNE DOBSON

AND THE MEMORY OF KAREN DANDURAND

(19462011)

WITH LOVE AND GRATITUDE FOR WHERE THIS

CONVERSATION BEGAN

These Fevered Days to take them to the Forest

Where Waters cool around the mosses crawl

And shade is all that devastates the stillness

Seems it sometimes this would be all

F1467

CONTENTS

On the surface, Emily Dickinson lived an ordinary life: she resided in one town, went to school, never held a job, lived in her parents home, remained single, and died at age fifty-five. To many who knew her, Dickinsons only acclaim was winning second prize for her rye and Indian bread at the annual cattle show. When she died, her death certificate listed her occupation as at home. Dickinsons internal world, however, was extraordinary. She loved passionately, wrote scores of letters, anguished over abandonment, fought with God, found ecstasy in nature, embraced seclusion, was ambivalent toward publication, and created 1,789 poems that she tucked into a dresser drawer. Only after her death, when her sister opened the drawer, did the world begin to realize that the life of Emily Dickinson was far from commonplace. My Business is Circumference, she once declared, and the work she produced over a lifetime is dazzling.

These Fevered Days takes its cue from Dickinsons own words:

This was a Poet

It is That

Distills amazing sense

From Ordinary Meanings

And Attar so immense

This book intentionally concentrates, extracts, and distills Dickinsons evolution as a poet. It does not claim to be a comprehensive, cradle-to-grave biography. Rather it seeks to shed light on ten pivotal moments that changed her. Too often, readers see Emily Dickinson as an artifact in amber: an eccentric spinster who locked herself away from the world. That perspective, while incorrect, is partially understandable. Dickinson did indeed keep herself at a distancein her own lifetime and ours. Biography first convinces us of the fleeing of the Biographied , she wroteas terse a warning to future biographers as there ever was. Yet while part of Dickinson will always be unknowable, much can be discerned. There are the poems to help us, of course. Fragments, too. Volumes of letters also are essential. And thousands of archival documents related to her life in Amherst, Massachusetts; her education; her travels to Washington, DC, Philadelphia, and Cambridge, Massachusetts; her reaction to the Civil War; and memories about her from family and friends. The tangible world surrounding Dickinson is another resource: her home, the paths she walked, the flowers she loved, the light in her bedroom. For Americas most enigmatic and mysterious poet, Emily Dickinson left a trail of clues.

Readers unfamiliar with Dickinson may benefit from a brief biographical overview that situates these ten moments. Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10, 1830, to Edward and Emily Norcross Dickinson. She had an older brother, Austin, and younger sister, Lavinia. Her father was a lawyer, and later a politician. Her mother kept the family home. Emily received superior schooling at Amherst Academy, and Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in nearby South Hadley, Massachusetts. She had many friends, andearly onteachers commented on her facility with words. When she returned home after one year at Mount Holyoke, she settled in, helping with housework and making social calls. The tedium wore on her. Her first publication appeared in an Amherst College student magazine when she was twenty-one. The prose worknot poetrywas printed anonymously. A few years later, The (Springfield, Massachusetts) Republican published her first poem, also anonymously. Emily Dickinson remained single, and gradually became reclusive. The familys financial status made it possible for Emily to stay home and not teach, sew for a living, or have other outside employment. By her late twenties, she was seriously writing poetry and gathering her verse into hand-sewn packets later called fascicles. She shared her love of words with her beloved sister-in-law, Susan, who read her verse and offered advice.

When Emily was thirty-one, she took the uncharacteristic step of sending several of her poems to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a well-known essayist who had published an Atlantic Monthly article offering advice to aspiring writers. Higginson would become Dickinsons literary mentor and one of the most important people in her life. He read her poems with interest, tried unsuccessfully to correct them, andwhile continuing to write hereventually gave up offering critiques. After the Civil War broke out, Emily composed poetry with the greatest intensity of her lifesometimes a poem a day. These were compressed verses with striking imagery that focused on her great literary themes of nature, faith, pain, love, and immortality. Toward the end of the war, Dickinson faced a medical crisis. She worried she was losing her eyesight. Emily traveled to Boston on two occasions to be treated by a physician, and lived in a Cambridge boardinghouse. When her personal trouble was finally behind her, she met Higginson face-to-face. That 1870 meeting was remarkable, and Higginsons vivid memory of it offers the best account ever recorded of what it was like to sit across from Emily Dickinson and hear her talknonstop. As her reclusiveness intensified, so did the mysteries around her. One riddle concerned Charles Wadsworth, a minister Emily had met on a trip to Philadelphia. The two had written each other and Wadsworth had visited the Homestead. There were also three Master Lettersdrafts or possibly copies of mailed letterslater found among her papers. No one knew who the unidentified Master was, or even if he actually existed.

As she grew older, one person Emily knew as a child came back into her life: Helen Hunt Jackson. Jackson had become a renowned poet, essayist, and novelist. She also was a friend of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and he reacquainted the two women with each other, and their literary work. In 1876, Helen visited Dickinson and implored Emily to submit her verse for publication. The poet refused. In her final years, Emily Dickinson endured one loss after another. First her father, then friends, then others close to her. She kept writing, but admitted, the Dyings have been too deep for me. Ill health overtook her slowly and she died on May 15, 1886. She was buried next to her parents in West Cemetery in Amherst. Emily Dickinson had published only a handful of poems during her lifetime, and all anonymously. It was not until after her death, when her sister discovered sheet upon sheet of poems, that the staggering sweep of her literary achievement became known. The first edition of her poems was published posthumously in 1890.